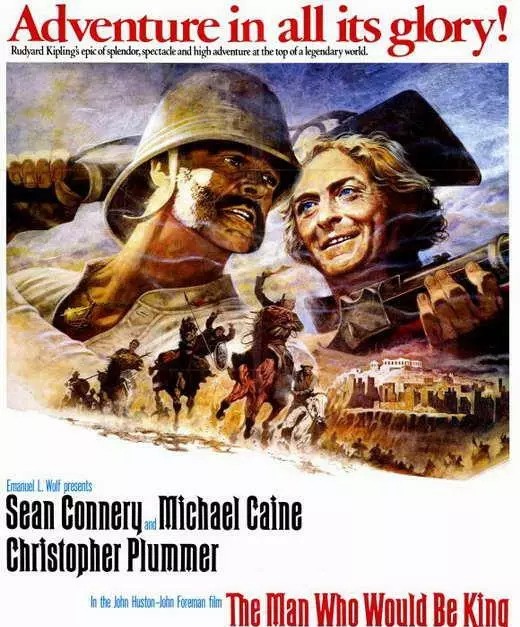

Variation on the director’s earlier The Treasure of the Sierra Madre as a pair of British ex-military cheekie chappies whose reach exceeds their grasp come unstuck when confronted by powerful religious elements. Enticingly presents a marvellously ironic puzzle – you can have everything your heart desires except anything that would make you human. And elevated less by John Huston’s cinematic achievement than by terrific performances by the two stalwarts of the British film industry at the time, Sean Connery and Michael Caine, the former taking the acting kudos by a nose as the less intelligent of the duo. Given Connery’s standing at the time, this was somewhat playing against type. Yes, he exudes screen charisma and is a macho as ever, but nonetheless not quite as quick on the uptake as the more calculating Caine.

Story is told in flashback after a maimed Peachy Carnehan (Michael Caine) turns up as the offices of journalist Rudyard Kipling (Christopher Plummer). They originally met when Peachy had stolen the writer’s watch, returning it on realizing they were fellow freemasons. With buddy Daniel Dravot (Sean Connery), they attempt to enlist Kipling in a blackmail scheme and in due course the soldiers set off to make their fortunes in the forbidding land of Kafiristan, at the top of the Indian sub-continent, where no white man has set foot since Alexander the Great.

Their scheme is simple – to hire themselves out as mercenaries to various tribes, bringing modern warfare skills and weaponry to primitive society and ascending the ranks of power. When Daniel appears unhurt after plucking an arrow out of his chest, the natives confer on him the status of god, and so he is elevated to kingshippery and all the gold he could want. But in this Garden of Eden there is a humdinger of a Catch 22, the apple he must not touch.

He can’t take a wife.

You can see the logic. As a god you should be above base earthly desires. A god could not possibly wish such intimacy with a human. Otherwise he would lose his otherworldly sensibilities, not to mention that the chosen woman would expect to physically explode. While the more sensible Peachy has been all the time calculating just how he’s going make a getaway with as much gold as he can carry, Daniel becomes trapped in the notion that he can have his cake and eat it.

The religious hierarchy says otherwise and it doesn’t end well.

Audiences may well have been disappointed at the lack of action. There’s only one battle and it’s over in a minute, albeit that there’s a timeout to make the point about the power of religion. And although our boys endure a momentous trek it’s fairly standard stuff and Huston lacks the vision of a David Lean to turn the journey into anything more dramatically or visually memorable. A whole bunch of indigenous background material – including the ancient version of polo where the ball is a human head – doesn’t make up.

What does transform this relatively slight tale is the playing. Connery and Caine are a delight, the kind of top-of-the-range double act on a par with the cinemagical pairing of Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973). They spark each other off just a treat. Caine, surprisingly, is the one in charge, Connery adrift in matters of arithmetic, strategy and, when it comes down to it, common sense even though when called up to judge on civil matters proves himself relatively astute and fair.

The writing, too, seems to understand implicitly how to get the best out of the characters. When they fall out, it is so subtle you would hardly notice. Caine scarcely bristles when Connery explains that Caine really should be falling in line with the rest of his subjects and bowing his head, but if you are astute reader of an acting face you can see the chasm that has opened up in their relationship.

To employ a Scottish phrase, Connery gives it “laldy” – acts with gusto – when playing the part of a madman, whirling around like a demented dervish, but mostly reins it in.

The intricacies of freemasonry would wait a few decades before called to the cinematic altar in The Da Vinci Code (2006) but here the mumbo-jumbo proves less important than, as with the Dan Brown epic, a symbol, and, again with the lightest of narrative strokes, we are left considering its mystic origins.

John Huston (Sinful Davey, 1969) back on top form but he’s more than helped by exceptional acting by Sean Connery (The Hill, 1965) and Michael Caine (Play Dirty, 1968) with Christopher Plummer (Nobody Runs Forever / The High Commissioner, 1968) in unusually subtle form as well. Gladys Hill (Reflections in a Golden Eye, 1967) and Huston were Oscar-nominated for the the screenplay based on the Kipling short story.

Impressed by this performance I should warn you I feel a Sean Connery binge coming on.

1975 was a really good year for Connery. This and the magnificent THE WIND AND THE LION. Lots of good movie going that year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could as easily be writing a Magnificent 70s. Remember Wind and Lion as having a great trailer and a great catchline – “between the Wind and Lion is the woman, for her half the world will go to war.” I’m on a bit of a Connery binge so will probably catch up on that as well.

LikeLike

A John Huge-ston movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also found this:

“For more than twenty years director John Huston was interested in filming The Man Who Would Be King, a short story by Rudyard Kipling that Huston read when he was fourteen. On 9 Jul 1954, a DV news item stated that Huston would make the film for Allied Artists and, according to an undated Var news item published circa 1955 in the film’s file at AMPAS Library, Huston planned to begin principal photography between Nov 1955 and Jan 1956 in India and was negotiating to film in the Todd-AO process. On 17 Jul 1959, a DV article reported that Huston would direct the film in India for Universal-International from a screenplay by himself and Aeneas MacKenzie. The same article reported that previously, in Oct 1958, Huston had announced his acquisition of the film rights and planned to shoot the film independently in Afghanistan. Although none of the above news items mentioned cast members, a 22 Mar 1968 DV news item reported that Humphrey Bogart was considering the project before he died. In a 1975 documentary found in the added content materials of the DVD release of the film, Huston stated that he had Clark Gable in mind for the role opposite Bogart, but both actors died (Bogart in 1957 and Gable in 1960) before the film could be made.

According to a 12 Aug 1964 HR news item, producer Ray Stark of Seven Arts signed actor Richard Burton for the film, which Paramount planned to release. A 28 Oct 1964 HR news item added that Stark hired scriptwriter Anthony Veillor, who had written the screenplay for a 1964 Seven Arts production that Huston directed, The Night of the Iguana (see entry). Although a HCN news item reported that Marlon Brando would also star in the film opposite Burton, several other actors were considered for the role. A 22 Mar 1968 DV news item reported that a few years earlier Rod Taylor had been cast, and modern sources reported that Michael Caine, Peter O’Toole and Frank Sinatra had been considered as Burton’s co-stars. Modern sources also stated that at some point the combination of Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas was considered. A 19 Jul 1965 HR news item reported that Huston postponed the start date from Jan 1966 to Jan 1967 to await Burton’s availability.

8 Sep 1967 HR and 13 Sep 1967 Var news items reported that Warner Bros.-Seven Arts had acquired the film rights, and that the picture was considered “the most important acquisition” of the new company. A 22 Mar 1968 DV news item announced that Martin Ritt would produce and direct the film from Veillor’s script for Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, but on 13 Nov 1968, an HR news item reported that Ritt was leaving the project. An 8 Aug 1973 Var news item reported that Huston was again set to direct, and that producer John Foreman and actor Paul Newman were interested in the project. Modern sources stated that Huston was considering re-teaming Newman and Robert Redford, who was Newman’s co-star in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973).

In a 12 Dec 1974 DV and other news items, Allied Artists and Columbia announced that the studios would jointly produce and distribute The Man Who Would Be King, which would star Connery and Caine (“Peachy Carnahan”), and would be directed by Huston from a script that Huston and his long-time assistant, Gladys Hill, wrote. Although a 27 Jan 1975HR news item reported that Barbara Parkins would appear in the film, and a 2 Mar 1975 LAT article reported that Tessa Dahl, the daughter of actress Patricia O’Neal, was cast as the “princess,” the only female role in the film was portrayed by Shakira Caine (“Roxanne”), wife of Caine. Christopher Plummer was cast as “Rudyard Kipling.”

As noted in the end credits, the film was shot on location in Morocco and on the Grande Montée, Chamonix, France, and was completed at Pinewood Studios, London. A 10 Jan 1975 DV news item reported that filming began in Marrakesh, Morocco, where, according to studio publicity materials, the Marrakesh Railway Station served as the story’s Lahore station, and an open square was used to film a market sequence. The publicity materials reported that approximately thirty locations were used in the film around the Marrakesh and Ouazarzate areas. The village of Tagadirt-el-Bour was used as the Kafiri village, Er-Heb, and the battle sequence between the Er-Heb and Bashkai was shot at Tifoultout near Ouazarzate. Another location site mentioned in publicity materials was Gorges du Todra at Tinghir, which served as the Khyber Pass. The caravan procession was shot at Ait Benhaddou, and Tanahoute was used to depict the Holy City of Sikandergul. According to a 10 Mar 1975 HR news item, the Moroccan government cut production costs by building a two-mile road through the Atlas Mountains for the filmmakers that could later be used by local inhabitants.

According to a 2 Mar 1975 LAT article, a twelve-week shooting schedule was planned and 500 local people were used as extras. The 1975 documentary found on the film’s DVD release reported that Karroom Ben Bouih, who marked his only film appearance as the high priest, “Kafu Selim,” was a local night watchman and approximately one hundred years old. The same documentary reported that the rope bridge in the story took about six weeks to build, and that during the sequence when the bridge was severed, Connery performed his own stunt by dropping about seventy to eighty feet and landing on cardboard boxes and foam rubber pads.

The picture closely follows Kipling’s original short story, although Huston enhanced the Masonic theme for the film. Another change made by Huston and Hill was the character played by Plummer, who in the short story was not given a name, but, like the real Kipling during his early career, worked for a small newspaper in Lahore. At the end of the short story, Peachy does not leave Daniel’s head with the reporter, but takes it with him, then dies a few days later without the head in his possession. The lyrics to the hymn by Reginald Heber, “The Son of God Goes Forth To War,” is sung by Daniel several times in the film and also appears in Kipling’s story. In the film, the words are sung to the tune of a traditional Irish melody, “The Moreen,” which is better known as “The Minstrel Boy.” The tune is a major theme in the soundtrack and is heard intermittently throughout the film.

A 24 Jan 1978 DV article reported that Caine and Connery filed suit against Allied Artists, seeking $109,000 each. They maintained that they were each due five percent of the gross profits from the film, but had only received $301,254 of the $410,400 total. According to a 5 Jul 1978 DV article, Allied responded with a counterclaim suit of $21,500 for defamation of character. In a 1 Aug 1978 DV article, Caine stated that he and Connery had resolved their differences with Allied and, although no monetary figure was mentioned, the article reported that it was understood that the actors received a “substantial portion of the sums they claimed they were owed.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Thanks for doing all the hard work on this. It’s good enough for one of my Behind the Scenes articles. I knew Huston had been working on this for years. Any of the pairings would have worked very well. but i have a soft spot for the Connery-Caine teaming.

LikeLike

Any chance I could just use this in my blog. It’s so fascinating. I’d credit you of course. I think more people would see it that way than would maybe read the Comments section. I could credit you as Fenny100 or with your real name.

LikeLike