Think of this as having been made before Star Wars (1977), Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Alien (1979), heck even Star Trek (1979), changed the sci fi world forever and imagine it’s a huge advance SFX-wise on the 1950s vanguard of sci fi pictures and you’ll probably come away very happy. A lot to admire in the matte work and some groundbreaking effects and actually the story – mad scientist lost in space – has a bit more grit than was normal for the genre.

But it’s laden down with talk and the action when it comes resembles nothing more than a first draft stab at the light sabers of Star Wars and clunky robotic figures that come across like prehistoric Stormtroopers. A bit more light-hearted comedy than in the other three mentioned, various quips at the expense of the robots.

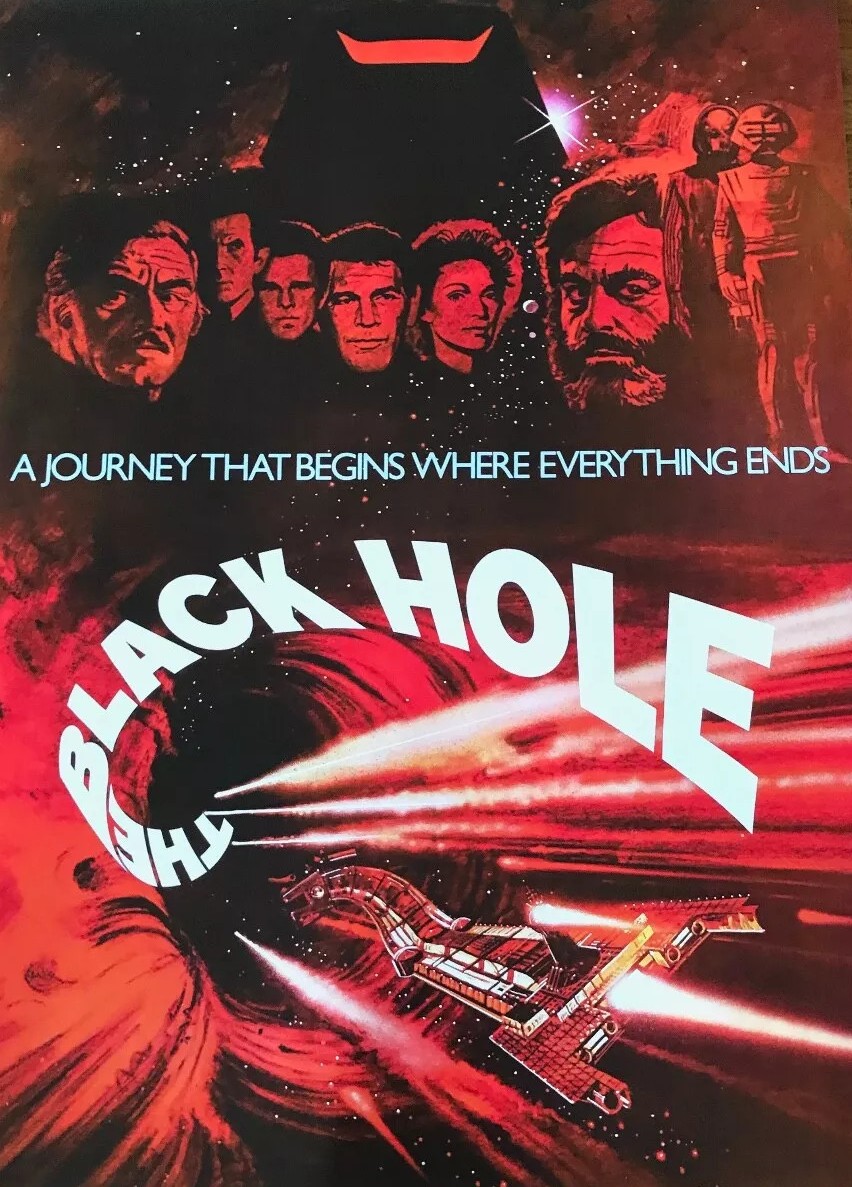

Scientists aboard space ship USS Palomino, a research vessel looking for life in space, is astonished to discover, hovering on the edge of a black hole, a missing spaceship USS Cygnus and are even more astonished to find out it’s not uninhabited, still on board is heavily-bearded Dr Hans Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell) and an army of robots that he has miraculously fashioned during his time lost in space.

This is a bit of an emotional blow to Dr Kate McCrae (Yvette Mimieux) whose father had been part of the crew of the Cygnus. Dr Reinhardt seems kosher enough except for his idea of, in the true spirit of space adventure, blasting off through the black hole. Although Reinhardt has been exceptionally clever in monitoring the invasion from the visitors and nullifying any threat with a blast from invisible laser, once they are on board that monitoring capability appears to vanish, allowing the visitors to search the ship where they find out that Reinhardt’s story doesn’t seem to add up.

Apart from Dr McCrae, the other personnel from the Palomino comprises Capt Dan Holland (Robert Forster), Dr Durant (Anthony Perkins) – the most inclined to follow Reinhardt into the greatest danger in the universe – quip merchant Lt Pizer (Joseph Bottoms) and dogsbody Harry (Ernest Borgnine). Plus there’s a cute robot Vincent (Roddy McDowall) constructed along even more rudimentary lines than R2-D2.

Vincent turns out to be a whiz at a basic version of a computer game, something between Space Invaders and Kong. But his main task is to wind up the crew with a head teacher’s supply of wisdom, spouted at the most inopportune moment. Except for the chest-bursting appearance of Alien, this might have garnered more kudos for the creepy mystery element – Reinhardt has lobotomized his crew members, turning them into these jerky robots, after they mutinied in revolt against his plan to dive into the black hole. Dr McCrae nearly joins the lobotomy brigade. And once she’s rescued it’s a firefight all the way. A stray meteor is on hand to add further jeopardy. And in the end the good guys are forced to plunge into the apparent abyss of the black hole, only to be guided by some angelic light and come out the other end unscathed, no worse for enduring the kind of phantasmagoric light show Stanley Kubrick put on in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

By this point Maximilian Schell (Judgement at Nuremberg, 1961) was an accomplished bad guy, covering up inherent malignancy with charm and scientific gobbledegook. Joseph Bottoms (The Dove, 1974) is the pick of the incoming crew but that’s because he’s been dealt a stack of flippant lines. Anthony Perkins at least gets to waver from the straight-laced. But everyone else is a cipher, even Yvette Mimieux (Light in the Piazza, 1962) who might have been due more heavy-duty emotion.

This was the 1970s version of the all-star cast, all the actors at one point enjoying a spot in the Hollywood sun, but now all supporting players. Schell was variably billed in pictures like St Ives (1976), Cross of Iron (1977) and Julia (1977). Robert Forster (Medium Cool, 1969) hadn’t been in a movie in six years. Anthony Perkins was waiting for a Psycho reboot to reboot his career – only another four years to go. Yvette Mimieux had only made four previous movies during the 1970s including Jackson County Jail (1976). The most dependable of these dependables was Ernest Borgnine (The Adventurers, 1970), for whom this was the 24th movie of the decade, including such fare as Willard (1971), The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Hustle (1975).

It didn’t prove a breakout picture for director Gary Nelson (Freaky Friday, 1976), Screenplay credits went to Jeb Rosebrook (Junior Bonner, 1972) and female television veteran Gerry Day.

Sci fi the Disney way.

I followed this film’s development for several years back in the seventies. It was yet another of Disney’s expensive and misguided attempts to recreate the magic of “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” (hot on the heels of the train wreck of “Island at the Top of the World”) while also showing that the studio could top “Star Wars” in the visual effects department.

The production got a fair amount of press at the time as legendary matte painter Peter Ellenshaw’s masterpiece/ swan song and for the hugely expensive motion control rig the studio built from the ground up. Ironically the only effects anyone raved about was the wire frame computer animation in the film’s teaser that was so popular it was retooled as the opening credit sequence.

The film blunders along on almost every front. The cast was a talented enough bunch yet lacked any chemistry although much of the blame has to be placed on the lackluster script and direction as well as the oddly grim tone. The inclusion of “cute” but charmless (not to mention horribly designed and executed) robots especially hurt the movie, particularly since audiences had already suffered through numerous such incarnations on American television in the previous year. Jerky miniatures and muddy opticals didn’t help.

Then there was that jawdropper mess of an ending that dragged audiences through literal hell and (maybe) back complete with a guardian angel coming to the rescue. Apparently there was an even worse ending originally shot where the crew survived falling through the black hole only to find themselves on the floor of the Sistine Chapel (I swear I’m not making that up). Much of the film’s tonal imbalance seemed to stem from conflicting creative visions that resulted in the shoehorning of both “2001” and “Star Wars” not to mention a little “Fantasia” into the story. If nothing else the flick is a fitting clusterfuck of a monument to the kind of corporate cluelessness Disney wallowed in during the decade after Walt’s passing.

Overall a disappointment yet somehow still weirdly watchable if one’s standards are dialed down. In the end the only memorable bits are Ellenshaw’s Eiffel Tower-inspired reimagining of Ralph McQuarrie’s Cygnus design and John Barry’s wonderfully bombastic score.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great stuff. Thanks for that. Forget about John Barry’s score and I’m a big fan of his.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Found this:

“Referring to the picture by the “tentative” working title, Space Probe One, a 24 Jun 1975 HR article announced a “percentage pact” deal between Walt Disney Pictures and writers Richard Landau and Bob Barbash for an adventure story set in outer space. Landau and Barbash had already spent one year working on the screenplay and were granted a portion of the film’s box-office gross, as well as an unstated flat fee for the script. The movie was set to become one of Disney’s highest-budgeted live-action pictures to date, with an estimated cost of $6 million, but Disney executives declined to confirm this amount. Landau and Barbash noted that their screenplay would be Disney’s first “disaster film,” with more than 200 characters dying in unspecific and non-violent ways. However, the studio maintained that the genre was “action-adventure,” and insisted on appealing to family audiences with a Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) G-rating.

The early Landau-Barbash treatment featured a colony of humans living in outer space, but its lead character was a robot. When the space station veers into a supernova, it is pulled into a black hole and its residents race to reach an escape capsule. To ensure authenticity, the writers interviewed scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, CA. Barbash told HR that principal photography was scheduled to begin in spring 1976.

A Jan 1980 Reader’s Digest article stated that the project was first conceived by filmmaker Winston Hibler, who produced and narrated many documentaries in Disney’s True-Life Adventures series. Before his death on 8 Aug 1976, Hibler hired Academy Award-winning Peter Ellenshaw to be the film’s production designer, and drawings for a space station were already underway. Walt Disney’s son-in-law and future president of the studio, Ron Miller, took over Hibler’s role as producer.

Four months after Hibler’s death, a 3 Dec 1976 HR article stated that casting was underway for the picture, now titled Space Station I. The story was set in the year 2125, and British filmmaker John Hough was named director. At the time, Miller had taken over as Disney’s executive vice-president of production and creative affairs, and was eager for the studio to venture away from animation to high-budget, live action filmmaking.

By 9 Aug 1977, Disney was formally preparing The Black Hole to be its most expensive live action picture to date, with an estimated cost of $10 million, according to an HR article published that day. The studio was thinking about changing the title back to Space Probe I, even though Richard Landau and Bob Barbash had been phased out of the scriptwriting process, and Jeb Rosebrook was listed as the film’s sole screenwriter. The story was now set in the year 2100. Although industry insiders speculated that Disney was ramping up production after the unprecedented box-office success of George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977, see entry), which was released several months earlier, Ron Miller explained that Disney’s space film had been in development for over a year, with a planned Christmas 1978 opening. However, the release date was pushed back to summer 1979. On 4 Jan 1978, HR announced that filming for Space Probe was scheduled to begin in Apr 1978.

Still, the project remained in limbo until late 1978. Referring to the picture by its release title, The Black Hole, a 13 Oct 1978 DV article announced that principal photography for the now $17 million production began two days earlier, on 11 Oct 1978, with a 122-day schedule. Gary Nelson was listed as director, and Gerry Day was added as a co-screenwriter with Jeb Rosebrook.

Although Jennifer O’Neill was initially cast in the role of “Dr. Kate McCrae,” she was replaced by Yvette Mimieux after O’Neill’s “recent” car accident, according to a 1 Nov 1978 Var news item. An undated, uncited contemporary news item in AMPAS library files and a 2011 autobiography by actress Linda Evans reported that Evans was considered for the role, and was set to replace O’Neill, but the filmmakers changed their minds in favor of Mimieux.

The Black Hole was the first film to take up all four soundstages at Disney’s Burbank studio, and the set was shrouded in secrecy. Two separate units worked independently, not knowing what their counterpart was doing, and few filmmakers were informed about how the movie would end. According to a 12 Jan 1978 HR news item, none of the actors were given a complete script.

In order to keep up with the special effects innovations of Star Wars and lure a new, teenage audience to Disney movies, the filmmakers invented two “special photographic effects” devices. Articles in the 22 Jul 1979 NYT and the Jan 1980 Reader’s Digest distinguished between “special effects” and “special photographic effects,” explaining that “special effects” were used to portray cinematic tricks such as weightlessness in space, but “special photographic effects” were needed to improve the quality and use of mattes, animation, and miniatures.

Production designer and miniature effects creator/supervisor Peter Ellenshaw, who had drawn plans for Winston Hibler in the early days of the production, wanted the space station to look distinct from real-life designs by the U.S.’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). He envisioned Cygnus as a “half-mile-long” skeletal structure of beams and glass, making it both transparent and ominous. As stated in Reader’s Digest, one of Ellenshaw’s paintings was “translated” into three separate, three-dimensional miniatures, one at a quarter-inch scale and the remaining two at a one-sixteenth scale. The miniatures took nine months and $250,000 to build, and were constructed with “hand-machined pieces of brass.” The models were enhanced by a thirty x forty foot canvas backdrop, portraying a “miniature galaxy.” It was backlit by 1,000 light bulbs shining through the same number of “star” pinholes.

Ellenshaw wanted the spacecraft to appear dimly lit, as if illuminated by a distant star, but this type of exposure required hours of filming. To defray the cost of man-hours, Disney spent $1 million to develop a computer “Automated Camera Effects System” (ACES) with WED Enterprises, Disney’s subsidiary for research and development. A 16 Nov 1978 HR brief, which announced the creation of ACES, noted that the camera was built through a partnership between the film’s director of miniature photography, Art Cruickshank, its composite optical photographer, Eustace Lycett, and an uncredited team headed by Disney executive Don Iwerks. In addition, David Snyder and David English were listed as the main “imagineers” on the project at WED, but neither is credited onscreen. The camera’s remote controls were lodged in “a multi-window shed” on the soundstage, and were capable of making thirteen separate movements at the same time. In the 22 Jul 1979 NYT, Cruickshank compared ACES to Lucas’s technology on Star Wars, noting that Disney’s camera was “superior” because it had the capacity to “turn, tilt, roll and pan.”

According to Reader’s Digest and a 3 May 1979 DV article, Peter Ellenshaw’s son, Harrison Ellenshaw, was an uncredited matte painter for Star Wars. He led a team of artists to complete 150 matte paintings for The Black Hole. The younger Ellenshaw told the 22 Jul 1979 NYT that Lucas’s technology only worked with “static shots,” so the Star Wars effects crew used quick editing techniques to create an illusion of movement over the mattes. In an effort to streamline the process of reshooting painted glass “mattes” over live action film, the Black Hole effects team invented the $100,000 “Matte-Scan” system, involving an “automated camera” that combined multiple live action shots on a single matte and conveyed motion. Harrison Ellenshaw noted that Matte-Scan allowed each shot of the matte cells to “have a little ‘drift,’” creating, “a depth of reality previously impossible.” He told HR that Matte-Scan’s computer both planned out and recorded camera shots, making it possible to repeat the exact motion multiple times. It took almost two years to fabricate, and was used for nearly 85% of the film’s matte sequences.

The robots in The Black Hole also represented a deviation from Lucas’s “See Threepio” (C-3PO) and “Artoo-Detoo” (R2-D2). Both Star Wars characters were performed by actors, while The Black Hole’s “V.I.N.CENT” and “B.O.B.” were completely mechanical. Director Gary Nelson feared the film’s technology would upstage the humanity of the story, so he emphasized personal relationships between the space station crewmembers and their robot colleagues.

The illusion of the black hole was created by a mixture of lacquer-based paint with a “whirlpool” of water. The spinning liquid was contained in a 6 x 6 foot clear plastic tank and filmed from below at 360 frames per second, fifteen times the regular shooting speed. The film was then taken to matte artists, who created “cross-dissolve triple frames,” and shot “with a painting of the black outside the hole.” During this effect, the artists used “diffusion glass” to slowly rotate the black painting. They also “burned in” additional elements, such as a piece of black velvet, spotted with white paint. Afterward, the layered image was projected “through an anamorphic lens” to create a flattening illusion, and the end result was a rotating ellipse rather than a perfect circle. A 15 Nov 1978 Var news item stated that Disney decided to use Technovision, a relatively new anamorphic lens at the time. Technovision was able to achieve the same 2:1 screen ratio as the more commonly used Panavision, but offered higher resolution and sharper images, according to a company spokesperson.

The end of principal photography was announced in the 9 May 1979 Var. Three months later, a 15 Aug 1979 Var article stated that Disney had six or seven weeks to finish the film’s special and photographic effects because Harrison Ellenshaw was due to leave the studio for Lucasfilm Limited. By 29 Aug 1979, Var reported a $17.5 million budget, but various contemporary sources, including the 22 Jul 1979 NYT and a 25 Jul 1979 Var news item, listed the final cost as $20 million.

The Black Hole marked Disney’s first PG-rated film, as reported in the 26 Sep 1979 Var. In the early stages of production, the 24 Jun 1975 HR stated that Disney intended to preserve their record of all G-rated films, and writer Bob Barbash admitted that he was required to omit the word “damn.” By late-Jul 1979, however, Ron Miller told NYT that the studio decided to keep “four-letter-words” in the film and were embracing the PG-rating since the studio was “trying to grow up slightly.” A 30 Apr 1999 LA Weekly news item claimed the rating was based upon the Anthony Perkins character, “Dr. Alex Durant,” being murdered by the spinning blades of the evil robot, “Maximilian.”

On 24 Oct 1979, Var announced that The Black Hole was scheduled to make its world premiere on 18 Dec 1979 at the Odeon Leicester Square cinema in London, England, with representatives of British royalty in attendance. The 25 Jul 1979 Var news item stated that the picture’s domestic debut was planned for 20 Dec 1979 at Plitt’s Century Plaza No. 2 theater in Century City, CA. The Los Angeles, CA, premiere was a benefit for the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), which had been established ten years earlier by an endowment from Walt Disney.

The Black Hole grossed $4,738,000 domestically its opening weekend, setting an all-time high for a Disney release, according to a 26 Dec 1979 HR news item. As of that date, the film was screening at 891 theaters, but only 830 had reported box-office receipts, making the projected earnings even greater than early estimates. By 23 Jan 1980, the picture had grossed over $27 million, as stated in an HR article published that day. At the time, Disney predicted The Black Hole would be their top-grossing picture to date. Almost two years later, DV announced that Disney’s Mary Poppins and The Black Hole were the top “homevideo bestsellers” of any studio, each earning over $1 million in less than six months of their video release.

The Black Hole has been reissued theatrically three times since its 21 Dec 1979 opening.

A 1 Dec 2009 HR article announced that Disney was planning a “reinvention” of The Black Hole with directors Joseph Kosinski and Sean Bailey, as well as screenwriter Travis Beacham. The film was set to mark one of the first projects developed by Disney’s new chairman at the time, Rich Ross. On 4 Apr 2013, HR announced that Disney had renewed the project, hiring Jon Spaihts to revive the script. Kosinski was still in line to direct, and Justin Springer was brought on as producer.

The Black Hole (1979) was nominated for two Academy Awards in the following categories: Cinematography and Visual Effects.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot. I saw it when it came out and hadn’t seen it since.

LikeLike

Saw it then too. I am still recovering.

LikeLiked by 1 person