In 1961, Hollywood was a casino. The advent of the roadshow and the lure of repeating the big-budget successes of Ben Hur (1959), Around The World In 80 Days (1958), Bridge On The River Kwai (1957) and The Ten Commandments (1956) had seen every studio sink colossal sums on the roll of the box office dice. United Artists had lavished $4m on three-hour epic Exodus about the formation of Israel with a star Paul Newman who had no blockbusters to his name. Columbia had sanctioned an even bigger budget, $5m, for war film The Guns Of Navarone.

Two studios were backing the directorial debuts of two major stars whose inexperience had seen both budgets soar. United Artists was part-funding John Wayne’s The Alamo while Paramount had too much riding on Marlon Brando’s western One-Eyed Jacks. MGM had a roadshow re-make of the 1931 Oscar-winner Cimarron with Glenn Ford and unknown Maria Schell in the leads. Even Disney had been tempted into the big-budget arena with Swiss Family Robinson, its most expensive live action movie.

None of these represented the biggest gamble of the year.

That honour, or should it be folly, went to the three small distributors bidding the unheard-of sum of $500,000 (the equivalent of $5m now) for the US rights for a three-hour Italian black-and-white Italian arthouse film, La Dolce Vita, directed by Federico Fellini. Despite the success in America in the 1950s of films like the Japanese Seven Samurai and Fellini’s previous La Strada and the current vogue for Swedish director Ingmar Bergman (The Seventh Seal) and the French New Wave, the marketplace for arthouse movies was tiny.

For marketing, arthouse exhibitors depended on movies winning prizes at film festivals or being directed by someone who had previously won such a prize. In the past decade only a handful had ever made $1m. Even the most successful of the recent spate of British films, classed as imports, such as Room at the Top, driven by massive publicity from its Oscar nominations and wins, had barely hit the $2m mark. The most successful foreign-language art movie had been Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman, which had grossed $7.5m. But that had starred Brigitte Bardot in a state of some undress.

Fellini was certainly a solid arthouse marquee name, having been awarded the Oscar for Best Foreign Film in successive years for La Strada (1956) and Nights of Cabiria (1957). In this he had matched the director credited with Italy’s post-war movie renaissance, Vittorio De Sica, who had also won Honorary Oscars (predating the Foreign Film category) for Shoeshine (1946) and Bicycle Thieves (1948). But Fellini was also aligned with the wider European New Wave, in 1958 forming a loose partnership with French directors Jacques Tati (M Hulot’s Holiday) and Robert Bresson (Diary of a Country Priest). Tati had his own company and had already invested in Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac and there had been talk of Fellini directing Tati in Don Quixote.

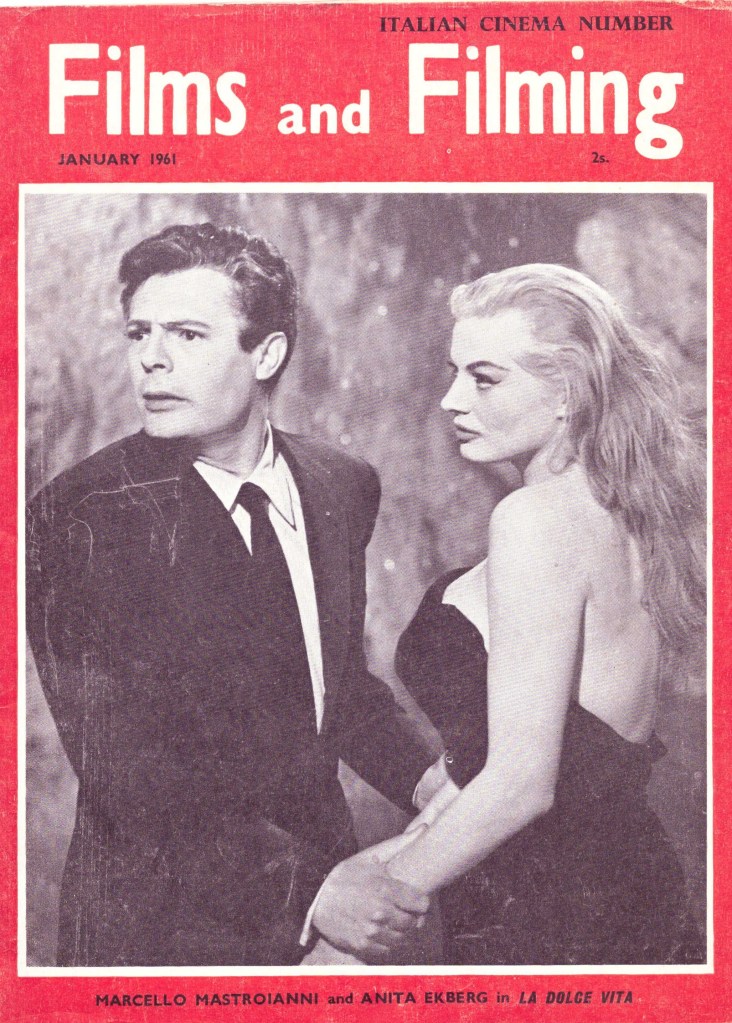

Filming of La Dolce Vita began in February 1959 with a cast including Marcello Mastroianni, Swedish actress Anita Ekberg and Anouk Aimee. Based on the performance of his previous films, producers Cineriz were dubious about its commercial prospects, but went ahead because it was a prestige picture. When the movie opened in Rome on St Valentine’s Day 1960, it astonished and shocked in equal measure.

The Catholic Church was outraged, demanding cuts, controversy boiling over when this met with refusal. Fellini had no truck with censorship. He said it was ‘dangerous in any way, in any occasion, because an artist cannot create under the sign of the guilty.’ Initial reaction to the movie was mixed; there was even a smattering of boos at the premiere. But some were already calling it a masterpiece.

Its opening weekend in Rome set a new house record of $16,000 (the equivalent to over $160,000 today) and then it broke every other conceivable record. In May it won the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Record giant RCA issued the popular theme tune by Nina Rota in Italy and in France a novelisation, La Douceur de Vivre, was published complete with screenplay and soon it would appear as an illustrated book in Italy with shooting script and behind-the-scenes photos. Fellini was already planning his next film, The Trip, to star Ekberg and Sophia Loren. After six months, still in its two launch cinemas, La Dolce Vita was taking $15,000 a week in Milan and $9,000 a week in Rome. By October it was outgrossing most new releases. By year’s end it had hoisted a sensational $1.125m in Italy. The season’s box office champion by a considerable margin, it left big-budget-Hollywood films in the dust.

Columbia Pictures, which had sizeable investments in European films, was quickest off the mark, purchasing in August the rights to distribute the film in the UK, where a November release was planned, and the British Commonwealth. Convinced the film was too controversial to receive a Production Code Seal (the censorship system of the time) in the US, nor wishing to drag the company name through any subsequent scandal, Columbia did not bid for the American rights. And so it became the tale of three companies, Omat Corporation, Embassy Pictures and Astor Pictures, who all had the same aim, to reinvent themselves through entering the arthouse business.

They were a disparate bunch. Omat had made its name reissuing old American movies which had been withheld from television. An abortive move into film production with Brotherhood of Evil had almost bankrupted it. But it had come back to buy a batch of Mexican films for distribution including Beyond The Limit starring Jack Palance and films with lurid titles like Never Take Candy From A Stranger. Embassy was run by Joe Levine, an independent distributor from Boston with an impeccable pedigree until he decided to relaunch himself in 1957 as a wheeler-dealer on a national scale, buying the rights to the Italian-made Attila the Hun starring Anthony Quinn and Sophia Loren and sending it into the American market on the back of more promotional dollars than it had cost to purchase. The next year, on a much bigger scale, he did the same thing with Hercules starring Steve Reeves, opening the movie with 600 prints nationwide in July. It made him a fortune. He followed up with films like Hercules Unchained and Jack the Ripper.

But soon he sensed a change in the marketplace and wanted to build up the prestige of his company away from the exploitation marketplace. ‘A small revolution is taking place,’ he told Variety, ‘among the major and independent circuit operations. Many large houses (cinemas) are converting to specialty and art policies. Demand for those films is growing. That’s for me.’

He bought a French film called The Law, directed by Jules Dassin, and changed the title to the more snazzy, and suggestive, Where The Hot Wind Blows. But by late 1960 he had another reason to be in hot pursuit of La Dolce Vita. He had missed out on Jules Dassin’s new movie Never On Sunday, at that time just opened in New York to record business. Astor Pictures was Embassy on a smaller scale, distributing exploitation films like The Girl in Room 13, Festival Girl and Yellow Polka Dot Bikini. The 30-year-old company had been taken over from the estate of Richard Savile in 1959 by a group including George Foley, financier and vice-president of City Stores Franklin Bruder, and Everett Crosby, brother of Bing and his business representative. Like Embassy, it had bigger aspirations, planning to release 10 features, the most in its history, including three produced by Crosby, in 1961. And then it saw an opportunity to crash the arthouse system.

Each company put in a bid in the region of $500,000 – an astronomical sum for an arthouse flick – for the rights. And each believed its bid had been accepted. In October 1960, Omat claimed it had a deal with Italian producers Cineriz for that sum plus a percentage and promptly announced the film on their distribution list. Joe Levine contested that, saying he had a ‘handshake deal’ that later turned into a ‘verbal agreement’, binding under Italian law, in front of two witnesses, for roughly the same amount. Astor also claimed victory. But in December Cineriz took out an advert in Variety declaring all claims were premature, as the US rights had not yet been granted. To everyone’s surprise, on January 7 1961, Astor was announced as the winner with a contract to prove it. They had outbid the others, paying a whopping $625,000 for the privilege. Al Schwartzberg of Omat complained: ‘All I know is we had a deal and nobody had told me different.’

Even more astonishing, Astor planned to spend a further $400,000 – more than the lifetime gross of most arthouse movies in the US – on promotion. Just to break even (since the cinema took about 50% of the gross), it would need to make $2.5m. In order to do that, it would have to achieve what had not been done since And God Created Women, guarantee an arthouse film a nationwide release. For a three-hour film foreign film without Brigitte Bardot, it was madness.

Astor wanted to start recouping their investment as quickly as possible. There was just one problem. That would prove impossible in the current system of releasing arthouse movies.

There were only a handful of such specialist cinemas, just 15 in New York, the biggest city in America. A New York opening was paramount, the gateway to the rest of the American arthouse circuit. The problem was every cinema was already tied up months in advance. Once a US distributor had bought a foreign movie it could take upwards of a year to find a New York cinema to release it in. And there had been a squeeze of another kind. The British New Wave was sweeping into America via the arthouse circuit and swallowing up screens wholesale. Since they did not require either dubbing or subtitles, British films were more accessible to American audiences, and cheaper for distributors.

Out of the approx 700 weeks playing time available annually at the New York cinemas, British films had accounted for 252 weeks (up from 154 the year before) compared to 85 weeks for French films and 45 weeks for Italian films. In addition, the majors had started to use arthouses for the kind of mainstream releases that would appeal to that particular audience. Even with arthouse films, there were trends, and there was a fear that American audiences would start to reject subtitled films altogether.

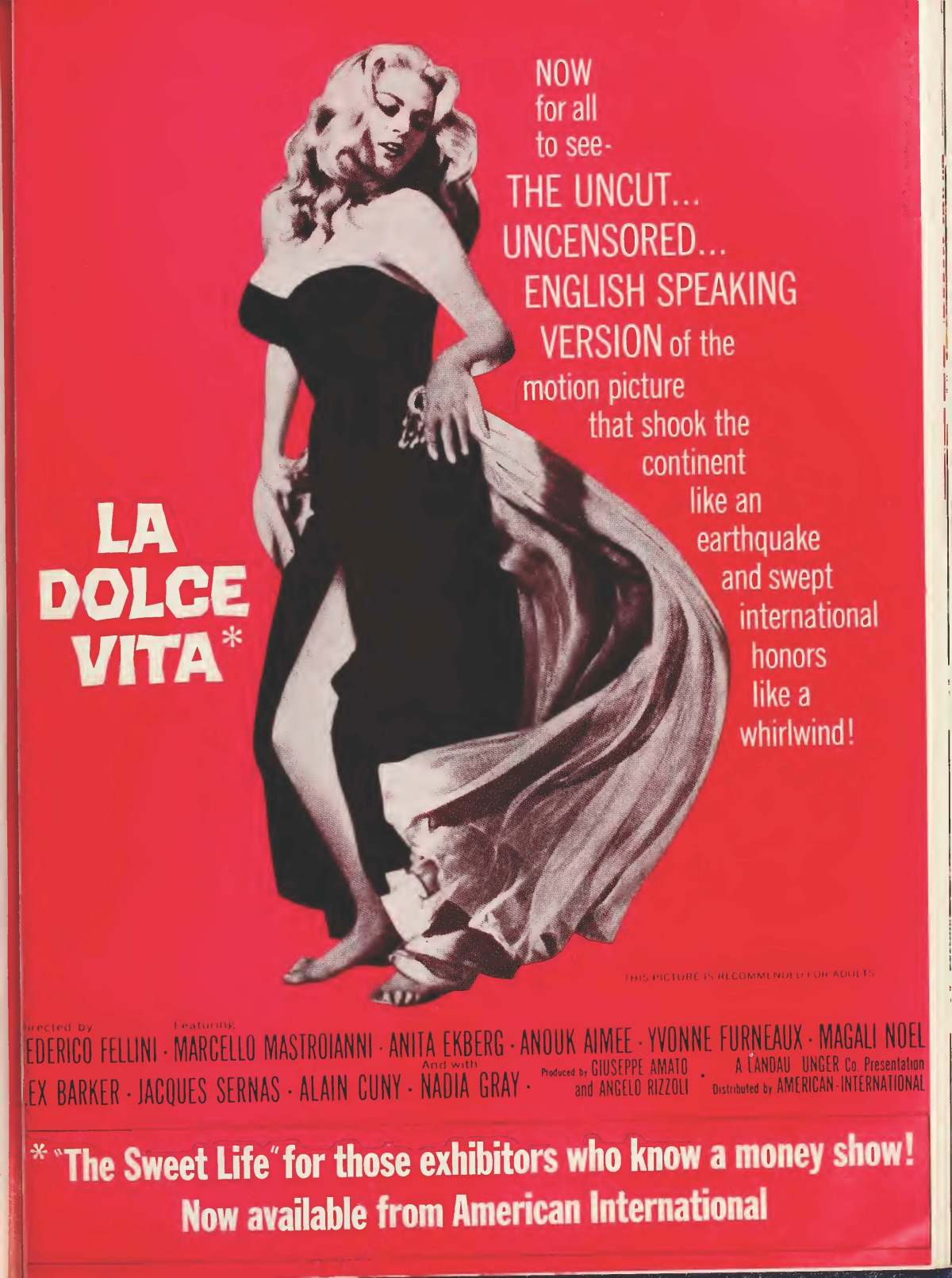

Never having played this game before, Astor decided to break the rules. To get round the Production Code, they simply did not apply for approval. Technically, they were within their rights; only films made by US companies were required to comply with the Code. After Room at the Top, which had not been passed by the Code, had won two Oscars earlier in the year, the exhibitors organisation (TOA) attempted to plug this loophole, aiming to force cinema owners to play only films passed by the Code.

Even United Artists, which had decided to release Never on Sunday through its subsidiary Lopert to avoid being besmirched by scandal, had submitted the film to the Code, receiving the worst rating. Still, there was no dodging the National Legion of Decency, at the time an extremely powerful force. The Legion passed its verdict whether you liked it or not. By normal standards, given the content, La Dolce Vita should have been condemned. But the Legion had a special category, for films with artistic merit dealing with dubious issues, and it decreed that La Dolce Vita was actually a moral film. Normally, Legion disapproval could boost a movie’s box office, since sophisticated arthouse movie buffs considered the Legion irrelevant. But that only worked if your target market was just the chic crowd. For Astor to have any chance of getting its money back, La Dolce Vita had to break out of the strictly arthouse market.

So Astor made a deal with the Legion. The Legion placed the film in a ‘separate classification’ and pronounced it was ‘animated throughout by a moral spirit.’ The Legion said, ‘The shock value is intended to generate a salutary recognition of evil as evil, sin as sin.’ Nonetheless, there were conditions. The film was cut by five minutes. Astor had to guarantee its advertising would have no prurient appeal, and, more important, agreed not to dub the film – the Legion felt dubbing would make the film more accessible to a younger, impressionable, audience. To show the film only in subtitles was a massive gamble, especially for the intended wider audience. Then Astor broke the rules again. Initially, in order to gain the impact it felt the movie required, it intended opening it on two arthouse screens in New York rather than one. But, of course, that was just doubling the problem. So with no cinema immediately available, it opened at the 946-seater Henry Miller Theatre in New York, which had never, in its history, shown a film, only presented plays. Astor had to guarantee the theatre $100,000 before the theatre was converted at a cost of $50,000.

Now Astor went for broke, and decided to release La Dolce Vita as a roadshow film. This move – arrogant, impudent or plain crazy, take your pick – was met with universal incredulity. The roadshow was the preserve of big-budget American-made major-studio widescreen colour films like Ben Hur not for foreign black-and-white interlopers. (Two foreign films had gone down this route before, The Golden Coach in 1954 and Tosca in 1958, but both had met with dismal failure). The only thing La Dolce Vita had in common with Ben Hur was the running time. In truth, Astor hedged its bets, also opening the film in the normal way in a proper cinema, the Gray Theatre, in Boston.

In New York, there was a reserved seat policy for each of the ten performances, one show per night plus matinees on Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. In Boston, there were four shows a day, starting at 11am with barely 10 minutes between each performance, and reserved seats at the weekend. There was one instant advantage to going roadshow – putting up the prices (called ‘hardticket’). How the film went out to other cinemas thereafter – if it went anywhere at all – would depend on which release technique proved more successful.

Astor embarked on the kind of campaign associated with a roadshow. There were adverts in newspapers and customised PR, it was featured in Life magazine and on television, a paperback tie-in was published and RCA issued six different singles of the theme tune. The trailer was unusual, a scattergun sequence of still images.

From the UK came encouraging news. As well as opening in December 1960 in the country’s most prestigious art house cinema, the 500-seater Curzon in Mayfair to a record gross of $11,000, La Dolce Vita had also opened at exactly the same time in a mainstream West End cinema, the 740-seater Columbia, the first time such a thing had occurred (called ‘daydating’ in exhibitor terminology), grossing $16,000. To put that in perspective, the week’s top film was Tunes of Glory which took $22,000 at the 1,400-seater Odeon Leicester Square. In January, each cinema was outgrossing the West End takes of Burt Lancaster in Elmer Gantry and William Holden in The World of Suzie Wong, which had opened in the same week as La Dolce Vita. At the Columbia it ran for 11 weeks, but was in its 18th week at the Curzon (still grossing a healthy $6,600) by the time it opened in the States.

On the other hand, by now, unexpectedly, La Dolce Vita had competitors for that sophisticated in-crowd. Major studio Columbia, which had baulked at Never on Sunday, had Mein Kampf scheduled to open in New York the same month. Jules Dassin’s Never on Sunday, which cost just $125,000 to make, was already doing terrific box office. On the one hand, the fact that a foreign film, equally controversial due to its content, was making money, could be construed as good. On the other hand, since the films appealed to the same audience, there were doubts whether the restricted marketplace could accommodate both. In addition, Never on Sunday had a far more popular theme tune, a singles chart-topper, the music acting as a powerful promotional tool for people who had never heard of the movie. And although the subject matter of Never on Sunday was prostitution, it was treated in such a light-hearted, charming, way that people fell in love with the film. And it had been made in English, not dubbed, so its appeal was instantly more universal.

Yet Never on Sunday demonstrated the pitfalls facing small distributors like Lopert and Astor. Black Orpheus, distributed by Lopert, had won the best foreign film Oscar in 1960, but the week it won was taken off the Plaza, the cinema owned by Lopert, because another film was pre-booked. There was just no flexibility in the arthouse industry. Like others in the market Lopert trod a fine line between art and profit. And in same month as Black Orpheus won the Oscar, Lopert announced twelve new films, more bread-and-butter than arthouse, including two horror films, one from Japan and one from Italy, and a Brigitte Bardot movie which would change its title from The Woman and The Puppet to the more sensational A Woman Like Satan. If a subsidiary of major studio United Artists could not survive in the arthouse field, what chance was there for an upstart like Astor?

Part Two tomorrow.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, La Dolce Vita and the American Box Office Bust-Out (Baroliant, 2018) ; “Brian Hannan Revisits La Dolce Vita,” Cinema Retro, No 33.

Wasn’t Cat on a Hot Tin Roof a blockbuster for Newman? Or Somebody Up There Likes Me? Prepared to stand corrected…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not big big hits for Newman. Cat was really Taylor’s picture and Somebody a middling success. I tend to sit down when corrected.

LikeLiked by 1 person