Commonwealth United, the makers of A Black Veil for Lisa (1968) reviewed yesterday, was one of a flood of new entrants to the movie business in the middle to late 1960s. Variety, which always liked to put an easy label on things, tabbed them “mini-majors,” “near majors” or “instant majors” in the belief that any outfit that could string together a substantial annual output was worthy of being considered a contender to become a major player in the great movie game.

A caste system had operated in Hollywood since the 1930s. The “Little Three” of United Artists, Universal and Columbia were considered inferior to the likes of the “Big Five” of MGM, Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox, RKO and Warner Bros. By the 1960s the smaller units had been promoted and Disney had taken the place of RKO. But with product at an all-time low, the U.S. Government was inclined to rethink its stance on monopoly and permit cinema chains to enter the business – the Paramount Decree of 1948 having expressly forbidden the opposite, of studios owning cinema circuits.

National General was the first to challenge the government dictat. The Government in the 1940s had prevented Hollywood studios from becoming involved in television but now did something of a U-turn in permitting television giants ABC and CBS to invest in movies made under the aegis of ABC-Cinerama and Cinema Center, respectively. More legitimate operations, by original Government standards, were the likes of Commonwealth United, American International (AIP), Embassy Pictures, and smaller units like Sigma 3 (in which producer Marty Ransohoff had a stake), Independent-International, Continental (backed by the Walter Reade arthouse chain) and Cinema 5.

The mini-majors could make movies much faster than the established studios which had millions of bucks tied up in projects, books and plays, paid for and never made, deals with talent that didn’t work out, as well as bigger overheads and interest on loans running at $2 million a year per studio. For a short period the newcomers did well in the box office sweepstakes, in 1970, for example, Cinema Center beat Warner Bros in market share. And with the product well running dry and big studios being more selective about release dates, that still left considerable “playing time unused by big companies” that could be filled by “low-voltage commercial product.”

I’ve covered the National General tale before so suffice to say it did most of the heavy lifting in challenging the Paramount Decree and made such pictures as The Stalking Moon (1968) with Gregory Peck and Eva Marie Saint, Elvis in Charro! (1969), El Condor (1970), and James Stewart and Henry Fonda in The Cheyenne Social Club (1970) and was influential in the distribution of films made by other mini-majors.

Commonwealth United began as a real estate company formed in 1961 that took over the Landau-Unger movie production company in 1967 and began the serious business of creating a large enough movie roster that would make it welcome to the distributor. In these product-famine times, anybody who could produce a movie could get a distributor, but the terms of the deal, if you were a one-off, favored the distributor. To achieve any kind of box office parity, you needed to show substantial intended output. Its initial entry into the business was as a distributor, in 1968 handling the U.S. release of spy thriller Subterfuge (1968) with Gene Barry, jungle picture Eve (1968), The Angry Breed (1968) mixing bikers and the movies, and heist picture Dayton’s Devils (1968), before biting the bullet with Italian-made A Black Veil for Lisa with British star John Mills top-billed.

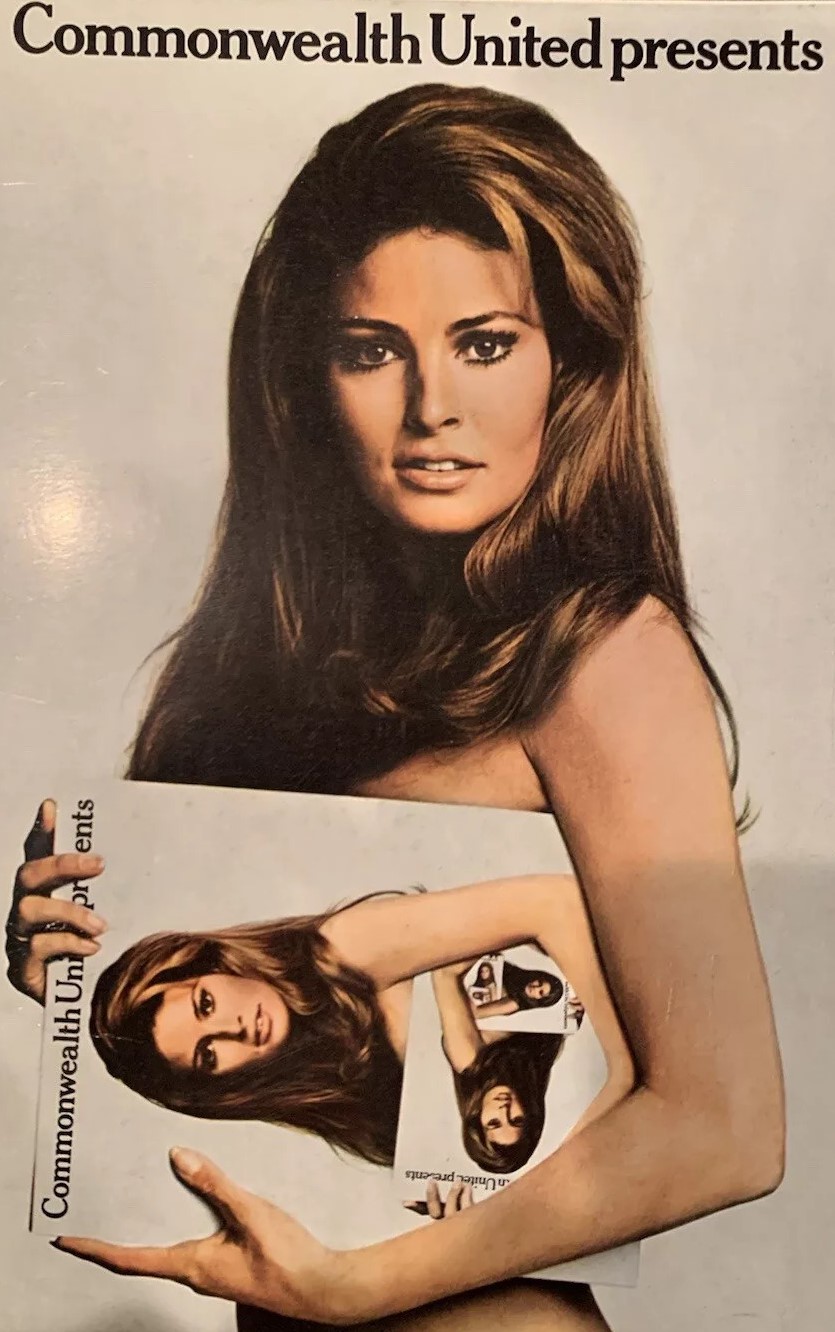

Commonwealth United couldn’t quite make up its mind whether to go down the A-movie or B-movie route. Its follow-ups to A Black Veil for Lisa were women-in-prison epic 99 Women (1969) and erotic thriller Venus in Furs (1969). But when it headed into the mainstream, it hit a box office barrier. Yugoslavian epic The Battle of Neretva (1969) with Yul Brynner flopped. Peter Sellers and Raquel Welch – snookered into fronting its lavish brochure, see photo above – couldn’t save The Magic Christian (1969). Robert Altman’s That Cold Day in the Park (1969) with Sandy Dennis, Julius Caesar (1970) starring Charlton Heston and The Ballad of Tam Lin (1970) with Ava Gardener all went down the tubes. The company closed down in 1971.

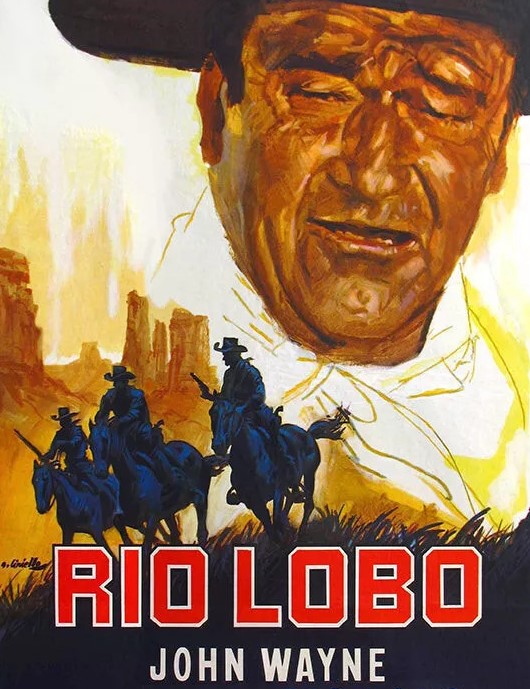

The bigger hitters, at least initially, promised more. Cinema Center, set up in 1967 using National General for distribution, and headed up by ex-Fox chief Gordon T. Stulberg, snagged deals with the likes of Doris Day, Jack Lemmon and Steve McQueen. Launch item With Six You Get Eggroll (1968) starring Day and Brian Keith was followed by some potential box office bonanzas – The Reivers (1969) and Le Mans (1971) with McQueen, John Wayne in Rio Lobo (1970) directed by Howard Hawks and Big Jake (1971), Richard Harris as A Man Called Horse (1970), Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970) with Dustin Hoffman and Faye Dunaway, William Holden in The Revengers (1971) and Lee Marvin and Gene Hackman in Prime Cut (1971).

But there was a high end price to pay. As with United Artists in the 1950s, Carolco in the 1980s and streamers today, big stars and directors took advantage of ambitious smaller companies. The price of even playing the game was high. Sure, there was reward. Little Big Man took in $15 million in rentals, The Reivers $8 million, Big Jake $7.5 million, A Man Called Horse $6 million. But that couldn’t stop the flow of red ink on calamities like early Michael Douglas vehicle Hail Hero (1969), Rod Taylor as a private eye in Darker than Amber (1970), Who Is Harry Kellerman (1971), Joseph Losey’s existential thriller Figures in a Landscape (1971) and a over a dozen more. Twenty out of 27 movies made a loss, the cumulative total running at £30 million. By 1972 CBS had had enough and closed shop.

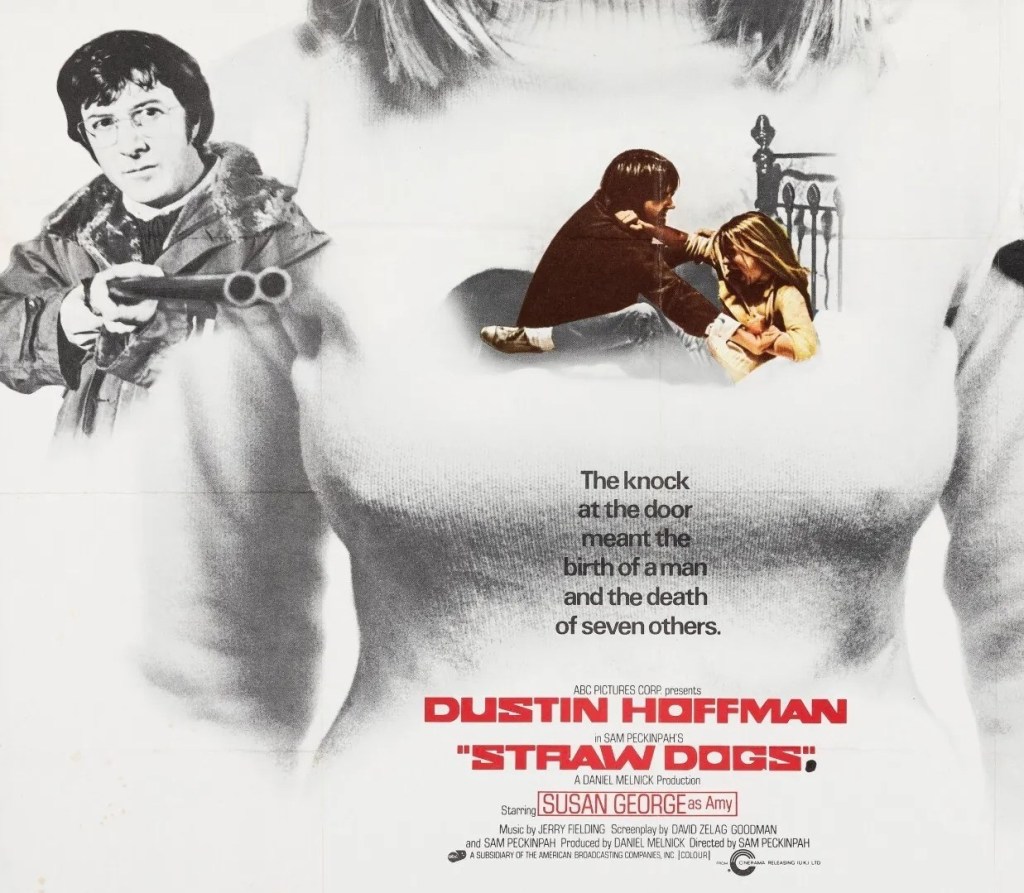

ABC released its pictures through an offshoot of Cinerama called Cinerama Releasing Corporation. It, too, struck occasional gold. Charly (1968) won an unexpected Oscar for Cliff Robertson. They Shoot Horses, Don’t They (1969) did the same for Gig Young and helped Jane Fonda be recognized as a serious actress. And big names signed on: Ingmar Bergman for The Touch (1971), Sam Peckinpah and Dustin Hoffman for Straw Dogs (1971). Robert Aldrich made three – The Killing of Sister George (1969), Too Late the Hero (1970) and The Grissom Gang (1971). With its biggest hit They Shoot Horses only picking up $5.5 million in U.S. rentals and For Love of Ivy (1968) with Sidney Poitier $5 million and the bulk of the others striking out, ABC pulled out of the movie business in 1971.

Cinema owner-turned-distributor Joe Levine had been a thorn in the side of Hollywood for many years especially after his imported Hercules (1958) showed you could sell anything to the American public if you put enough advertising dough behind it – a notion he signally undercut when all the money in the world couldn’t turn Jack the Ripper (1959) into a hit. He turned more legit, in Hollywood eyes at least, by teaming up with Paramount for The Carpetbaggers (1964) and Nevada Smith (1966) and funded Zulu (1964) – a hit most places except the U.S. After the critical and financial success of The Graduate (1968) and The Lion in Winter (1968) he sold Embassy to one of those conglomerates that had started sniffing around the business, Textron, and the company was renamed Avco Embassy. Kept on as president, he quit in 1974 and Avco Embassy pulled out of movies a year later only to re-enter the fold in 1977 and under Robert Rehme shift into lower-budgeted numbers like The Fog (1980) and Time Bandits (1981). He increased turnover fourfold. In later years, the company changed owners and names several times.

Some of the less well-publicized orgaizations lasted longer. Independent-International, set up by Sam Sherman, Dan Kennis and Al Adamson in 1968, kept budgets down to an average $200,000 a picture and reckoned that even with limited opportunity could pull in rentals of $300,000. After the success of biker picture Satan’s Sadists (1968), the company put 13 movies in circulation without troubling the New York first runs. Typically, a movie would garner 4,000-6,000 playdates. That company is still in existence.

Going back to where we started with Commonwealth United, you’re probably very familiar with American International for its Edgar Allan Poe, beach party and biker pictures. But in 1969 after co-founder James Nicholson quit and the company went public with the aim of entering the Hollywood mainstream, it relied on Commonwealth for distribution, releasing 31 pictures in this fashion. Beginning with adaptations of classics like Wuthering Heights (1971) and Kidnapped (1971) and moving onto big-budgeters like Force 10 from Navarone (1978) and still dipping into horror and exploitation AIP coninued in one guise or another until 1980.

SOURCES: “Nat Gen Readying 7th Film,” Variety, November 16, 1966, p4; “Instant Majors: A Short Cut,” Variety, October 25, 1967, p5; “Same Upper Uppers,” Variety, October 30, 1968, p12; “Commonwealth: Near Major,” Variety, February 19, 1969, p5; “Commonwealth Full Sell,” Variety, May 7, 1969, p7; “Nat Gen Rolling Six,” Variety, October 8, 1969, p6; “Topheavy Film Studios Fade,” Variety, October 29, 1969, p1; “Nat Gen Denies Phase-Out,” Variety, August 12, 1970, p5; “1970 Domestic Theaters Sweepstakes,” Variety, January 13, 1971, p38; “Today’s Majors As Instant,” Variety, July 21, 1971, p7; “American Int Expected Inheritor of Cinerama Releasing,” Variety, July 31, 1974, p3.

Very educational piece, I can forgive thriller being in italics for Figures in a Landscape and the extra The on both Time Bandits and Straw Dogs, and on this occassion, a warning will suffice…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was being generous.

LikeLiked by 1 person