Should have been a joyful reunion. Director Frank Capra linking up again with Columbia for whom he had won four Oscars in the 1930s and virtually single-handed lifted the studio out of the minor league. After coming unstuck with It’s A Wonderful Life (1946) – huge flop on initial release and not by this point having found its later more appreciative audience – he had backed off from Hollywood, only five more movies, none acclaimed, the last being the distinctly lightweight A Pocketful of Miracles (1961) with Glenn Ford.

Capra might have seemed a strange candidate for a sci fi picture given the bulk of his movies had been heartfelt comedies or dramas, but he’d become something of the go-to director for science fact programs, making, for Bell Laboratories, television documentaries on the sun, cosmic rays and the circulatory system. Dealing with the intricacies of space travel would have been catnip especially as he was in the process of making an industrial short Rendezvous in Space (1964) to show at the World’s Fair in New York that started in April 1964, and would, unexpectedly, proved to be his final production.

He’d bought the rights to the Matt Caidin bestseller on publication in March 1964 and and tied up a deal with Columbia’s first vice-president of worldwide production, namely Mike Frankovich who assigned the screenplay to Walter Newman (Cat Ballou, 1965). The novel was both simpler and more complicated. There was only one astronaut, Richard Pruett, and he faced the same problem of diminishing oxygen supply with old buddy Ted Dougherty planning to launch an untried Gemini as a rescue mission. But much of the narrative was given over to flashback, test pilot and trainee astronaut plus romance, with Russians planning to steal the rescue glory.

By June Capra was back on the studio lot prepping the picture and, still under the Frankovich aegis, it was announced as going into production in early 1966. So it took a good couple of years before Frankovich decided the Capra wasn’t, after all, the right man for the job.

By the time Capra was squeezed out, Frankovich was in the process of transforming himself into one of the new breed of producers, gamekeepers-turned-poachers, who had jumped from top level studio management into independent production. He prefaced his move by commenting, “Now that I’ve turned Columbia around and we’ve all these blockbusters,” it was time to head out to pastures new with the determined aim of “making a buck I can keep.”

But Frankovich was unusual in that prior to taking an executive role at Columbia he had made his bones as a producer (from serials and B-pictures to Footsteps in the Fog, 1955) in the 1940s-1950s. Frankovich set up an initial five-picture slate with Columbia comprising Marooned, The Looking Glass War (1970), Cactus Flower (1969), There’s a Girl in My Soup (1970) and Doctor’s Wives (1971), shortly after adding Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice (1969), half these titles scoring highly at the box office.

Columbia provided 100 per cent finance. Had he greenlit these pictures while at Columbia, he would have earned far less as a high-flying executive than as an independent enjoying a straightforward production fee plus a healthy share of the profits.

But having cut loose Capra, Frankovich waited until he had taken the project under his own personal wing in his new independent production company before hiring a replacement. He knew who he wanted and was willing to wait 18 months until his target, John Sturges, became free.

And in the way of neophytes wanting to make their mark quickly he did it in the usual manner – by making salary headlines. But rather than forking out for a marquee actor he made John Sturges the highest-paid director in Hollywood on a $750,000 fee, 50 per cent more than he had received for Ice Station Zebra (1968). He earned more than star Gregory Peck (on $600,000), still recovering from a box office trough. From six movies in the same number of years he mnaged only one hit. He should have worked with Sturges before now but had pulled out of Ice Station Zebra.

In fact, Peck was the only star in the Frankovich orbit. Apart from Walter Matthau in Cactus Flower and to a lesser extent Natalie Wood in Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice and Peter Sellers for There’s a Girl in My Soup, Frankovich banked on new, inexpensive, talent. None of the crew in the capsule for Marooned had any marquee status. He turned Goldie Hawn into a star with Cactus Flower and There’s a Girl in My Soup and gave a boost to the fledgling Hollywood careers of Christopher Jones (Wild in the Streets, 1968), Pia Degermark (Elvira Madigan, 1967) and Anthony Hopkins (The Lion in Winter, 1970) in The Looking Glass War. Both the careers of Wood and Sellers were on downward spirals before Frankovich intervened. Crenna and Hackman reunited for Doctors’ Wives along with Dyan Cannon from Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice.

John Sturges was a renowned gadget freak. He loved scientific detail, couldn’t get it out of his head that the Russians had beaten the U.S. into space. He dumped the Newman screenplay, dropping the romance, and despatched screenwriter Mayo Simon to Houston to research the NASA background, interviewing astronauts, wives, programmers, and to “spend a lot of time with the Apollo playbook.” The idea of sending three astronauts into space was already being considered by NASA.

But authenticity came at a price. The reality was that space travel proved every bit as dangerous as novelist Matt Caiden had imagined. In January 1967, three crew members preparing for space travel died on the ground testing equipment. Pressure mounted on Columbia to cancel the picture. The disaster severely dented the box office prospects of the distinctly lightweight The Reluctant Astronaut (1967). Frankovich changed tack and trimmed the tale so that it focused on the astronauts setting off for home only to discover their retro rockets won’t fire “and they don’t know why.”

Sturges decided not to opt for split screen, so effective in Grand Prix (1966) in telling a complicated story from multiple angles, and combined blue screen, hydraulics and models. A full-size Ironman One was mocked up and dangled on wires. Concerned the science might overwhelm the narrative, Frankovich, “afraid it wasn’t human enough,” instructed Simon to given the women “more to do” and humanize the Peck character (whose wife is not involved) by giving him a son of college age (though a scene between them was never used).

Frankovich didn’t stint on the budget now and splurged $8 million on the project and upgraded it to a 70mm roadshow. Nor was he so hung up on Columbia that he rejected an opportunity to film on MGM’s largest soundstage where production got underway in November 1968. Production ran through till April 1969, with Peck not required until February. Where the screenwriter depicted the astronauts as “dirty and unshaven and their capsule grungy and cramped like a phone booth,” Sturges opted for a cleaner, sleeker look, and in a bigger capsule.

The designers copied the Apollo 1 capsule and the orbiting laboratory was an early version of the Skylab. North American Aviation and Philco-Ford, suppliers to NASA, helped with designing elements of the hardware. Initially opposed to the project, NASA relented to sufficiently to permit use of its logo though stopping short of allowing access to its Houston HQ yet softening its attitude later on.

Some of the problems of filming space had already been solved – by Stanley Kubrick for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). But Kubrick wasn’t inclined to share his trade secrets, so Sturges went the low-tech route of wires, hydraulics and back projection. “The biggest problem was making everyone look weightless,” said Sturges, “We used every trick in the book.”

Sturges didn’t feel in competition with Kubrick. “Marooned was scientific,” explained Sturges. “It was about engineering. The Kubrick film was about evolution and the rebirth of humanity. One was nuts-and-bolts, the other poetry.”

By the time the film was released, Americans had landed on the moon and the first orbiting laboratory was about to launch into space. Nor did Sturges believe that astronauts could actually end up marooned, insisting that was “a possibility, not a probability” and that, in any case, methods of effecting a rescue were available.

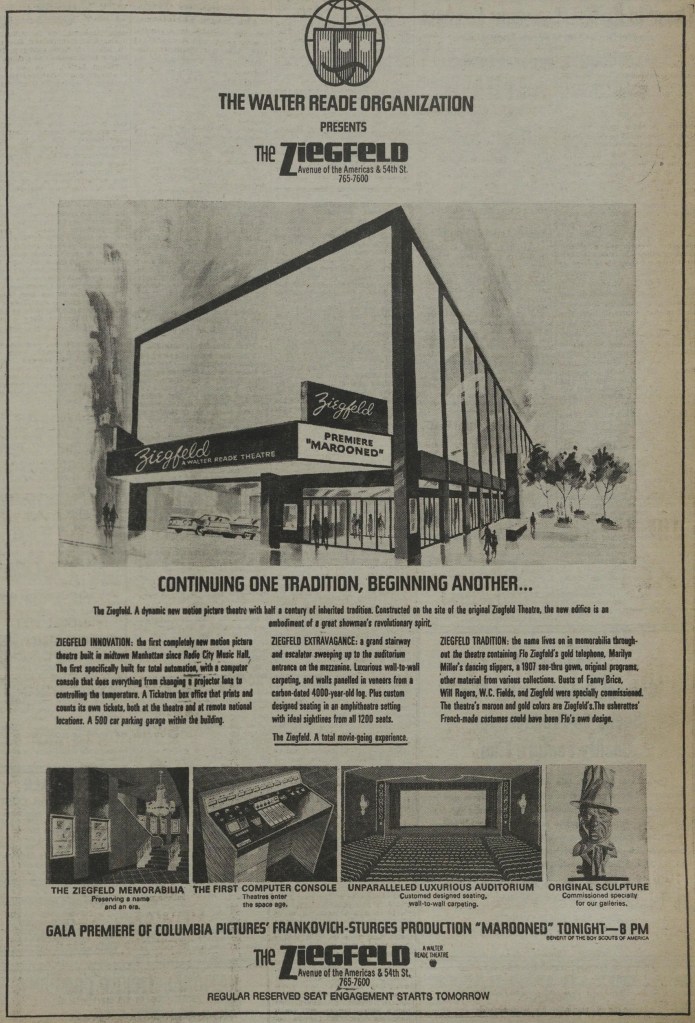

The movie was marginal roadshow length, but it was felt the subject matter and style was more akin in release terms to 2001: A Space Odyssey than Planet of the Apes. Some of the “original rough language” was cut to achieve a G-rating. It was the debut movie at the Ziegfield in New York, the first purpose-built movie theater in the city in decades. Box office polarized: opening to a smash $50,000 at the 1392-seater Egyptian in Los Angeles compared to a tepid $20,000 at the 1200-seat Ziegfield.

When Apollo 13 (“Houston, we have a problem”) in April 1970 looked as if it would end in tragedy, it could have spelled curtains for the movie, now well into its general release. The averting of the danger provided a box office boost but not enough and it racked up a very modest $4.1 million at the domestic box office. It won the Oscar for best visual effects.

Excepting Frankovich who signed a deal to make a further dozen movies for Columbia, nobody came out of this well. Peck only made three films in the next five years, Sturges quit Le Mans (1971) after seven weeks and only made four more pictures. Mayo Simon was given a crack at Sturges’ next project, back to World War Two, for The Yards of Essendorf, to star Warren Beatty, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Ursula Andress and a 500-ton snowplow, but that stalled on the starting grid.

SOURCES: Glenn Lovell, Escape Artist, The Life and Times of John Sturges (University of Wisconsin Press, 2008) p263, 268-271; Gary Fishgall, Gregory Peck, A Biography (Scribner, 2002), p266-268; “Hollywood Report,” Box Office, March 11, 1964; “Hollywood Report,” Box Office, June 29, 1964; “Columbia 83-Film Production Slate Biggest in History, Frankovich Says,” Box Office, January 3, 1966; “See Frankovich Going Indie Next Winter or Spring,” Variety, May 24, 1967, p3; “Mike Frankovich’s 5 for Columbia,” Variety, January 17, 1968, p3; “Flight of Exec Brains to Production,” Variety, July 24, 1968, p3; “Metro’s Stage No 27 for Columbia Film,” Variety, November 6, 1968, p24; Wanda Hale, “Producer: Chicken or Egg,” Variety, November 13, 1968, p32; Wayne Warga, “Author, Director, All Out For Space-Age Authenticity,” Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1969; “Nowadays Anything A Box Office Plus or Minus,” Variety, September 3, 1969, p6; “G for Marooned After Dialog Cut,” Variety, November 12, 1969, p3; “Picture Grosses,” Variety, December 17, p9; “Picture Grosses,” Variety, December 24, p9.

Yellow card for 2001: A Sapce Odyssey

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Corrected. I could say I put in misspellings to see if anyone notices but that’s not the case.

LikeLike

I tried that excuse but nobody bought it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sturges wanted to do The Yards of Essendorf with McQueen, but the doomed Le Mans intervened.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“When Apollo 13 (“Houston, we have a problem”) in April 1969…”…hmm…or possibly April 1970.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for pointing that out. Corrected the error.

LikeLike