Like many an actor during the 1950s and 1960s – and it’s still going on – James Garner wanted to take greater control of his career. But he’d been doing that since he started out in the business, going on such an almighty tantrum with Warner Brothers, whose television arm had provided his big break via Maverick (1957-1962), that it resulted in a heavily-publicized spat that ended up in court. Garner objected to the kind of square-jawed roles in relatively lightweight movies (Up Periscope, 1959, Cash McCall, 1960) that his employers deemed most suitable to build his screen persona. He hankered after for more complex material.

Mirisch came to the rescue, hiring him for The Children’s Hour (1961), though only in a third-billed capacity, but thereafter offering him a three-picture deal, an action that appeared to provide him with professional sanctuary and when he received $150,000 for The Great Escape (1963) his actions seemed justified and he was “pegged as the natural successor to Clark Gable.”

But his notion of what might appeal to audiences, the kind of amiable almost knowing-wink characters, didn’t go down as well at the box office as he might have imagined. And when he was cast as the lead – though, critically, not guaranteed above-the-title status – in 70mm roadshow Grand Prix (1966) his presence was blamed for the movie not doing as well as expected. And it was soon apparent to all that he was far from a box office high-flyer. In fact, on the domestic market, his movies always made a loss.

Except for The Art of Love (1965), where you could equally argue Dick Van Dyke was the main attraction after the success of Mary Poppins, the movies in which he had been the star (excluding the likes of Move Over, Darling, 1963 and The Americanization of Emily, 1964 where he played second string to Doris Day and Julie Andrews, respectively) took in an average rental of $1.5 million, way below what they cost to make.

He was viewed as a perennial loser in the hard-nosed world of Hollywood that took earnings as its sole measure. Worse, Variety held up to scrutiny his choices, complaining he had “forsaken tough guy roles for indifferent comic assignments and two misjudged roles as a tormented amnesiac” (36 Hours, 1964, and Buddwing/Mister Buddwing, 1966)

Sensing which way the wind was blowing, Garner set up his own production company. He was in good company – Burt Lancaster, John Wayne, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra among that coterie. Cherokee Productions was intended to be the vehicle by which he would control his own career and prove, once again, that he was better at it than any studio. His final movie as a purely salaried performer was Hour of the Gun (1967) the last picture in his Mirisch deal, which paid him “not much.”

Cherokee announced two pictures to be made in spring and summer 1967, Doll from the Ed McBain thriller and Buffalo Soldiers based on the John Prebble book and with director Ralph Nelson already in tow. Neither saw the light of day.

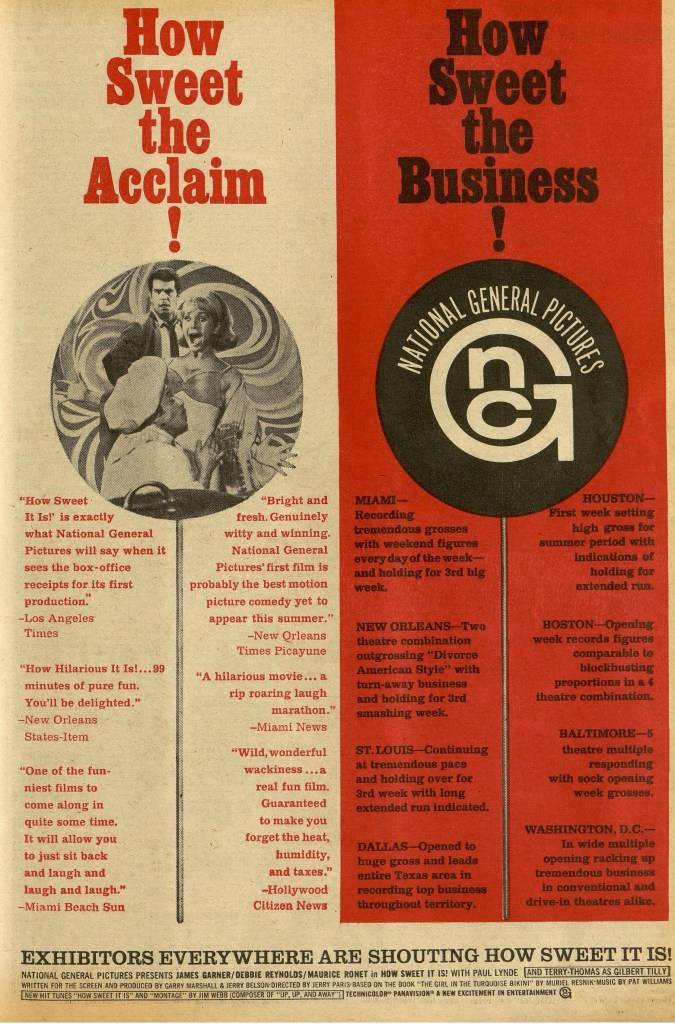

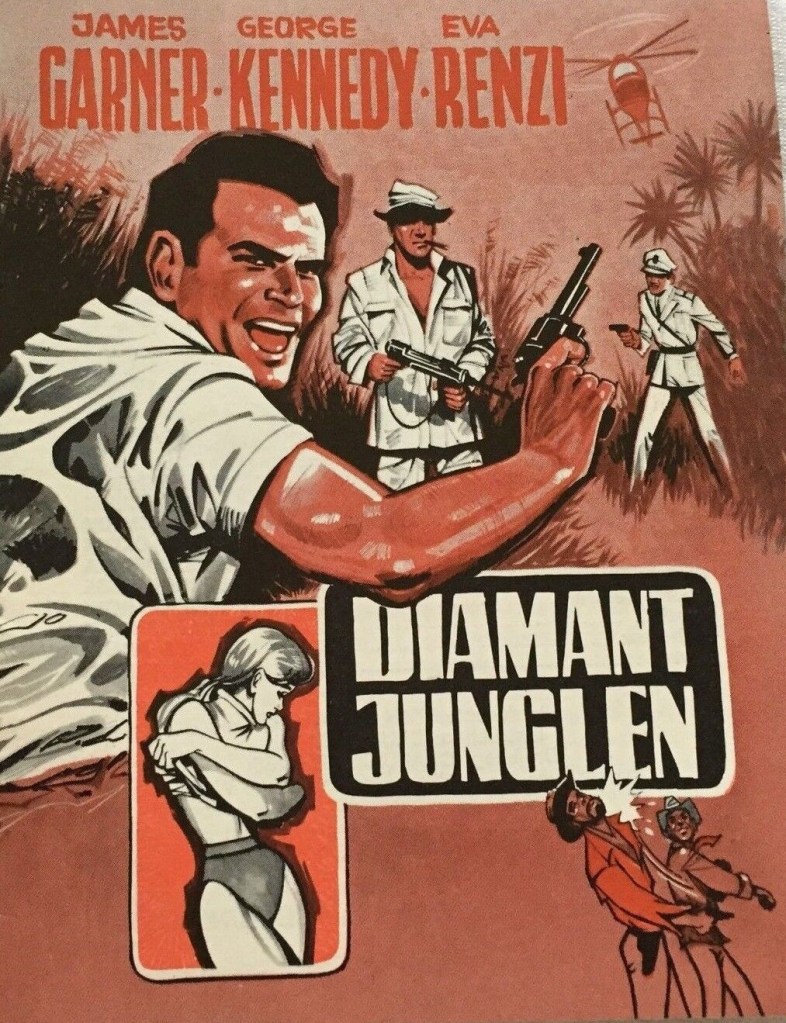

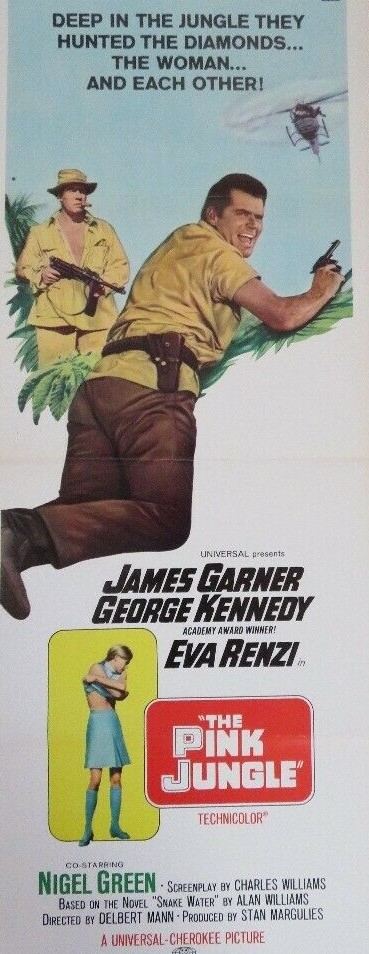

Undeterred, he tried again. This time the slate was more ambitious and achievable as it transpired: comedy How Sweet It Is (1968) co-starring Debbie Reynolds for nascent production company National General, adventure The Jolly Pink Jungle (thankfully retitled The Pink Jungle, 1968), The Sheriff (which became Support Your Local Sheriff, 1969) for United Artists and Buffalo Soldiers (still unmade).

The reason for original title for the “Jungle” picture might have been to avoid confusion with a musical earlier in the decade by Leslie Stevens called The Pink Jungle. According to some sources, it was originally intended to pair Garner with Shirley MacLaine. I never found any mention of her in my research and it seems an unlikely teaming, much as you could see how well it could play, since the actress’s asking price was $750,000 and that would make her the star rather than Garner and I’m guessing the script would be rewritten to tilt in her direction.

Given Universal was intent on not going anywhere near a live jungle it sounded, budget-wise, well out of the MacLaine league and more appropriate for the likes of rising – and cheap – West German star Eva Renzi (Funeral in Berlin, 1966).

The most studio Universal was willing to spend was to enlarge its jungle backlot by seven acres to 20 acres. Renzi had been due to make her Hollywood debut with House of Cards (1968), another Universal picture, opposite George Peppard but when she fell pregnant was replaced by Inger Stevens. The Pink Jungle didn’t get a good rep from anyone, least of all the critics. Garner complained about Renzi, and, even though he was the prime mover behind the picture, said he only did it “for the money” while for her part Renzi ragged Oscar-winning director Delbert Mann.

Neither of the first two Cherokee offerings did much to pep up Garner’s marquee value. How Sweet It Is, budgeted at $3.2 million, only returned $2.7 million in rentals in the U.S. and finished a mediocre forty-third in the annual box office league. The Pink Jungle didn’t feature at all which meant it took in less than $1 million.

Garner redeemed himself with Support Your Local Sheriff, made for a miserly $1.6 million but a worldwide hit, his best-ever performer as star. But oddly enough, it didn’t do that much for Hollywood perception. MGM initially rejected him for his next movie Marlowe (1969), another flop. Cherokee’s next two features, Italian co-production A Man Called Sledge (1970) and Support Your Local Gunfighter didn’t deliver either.

So Garner went back to television. And Warner Brothers. The upshot was J.G. Nichols (1971-1972), another western. The WB deal included movies but only one was made – Skin Game, 1971 – and neither that nor They Only Kill Their Masters (1972) for MGM or Disney pair One Little Indian (1973) and The Castaway Cowboy (1974) made much of an impact at the box office. And it wasn’t until, ironically enough, The Rockford Files (1974-1980), produced by Cherokee for Universal, that Garner really re-established his position in the industry.

SOURCES: “James Garner Moves from Actor Towards Future Producer Status,” Variety, October 5, 1966, p5; “James Garner’s Own Plot: Performer to Producer,” Variety, November 1, 1967, p18; “Peak Production Year for Universal Studio,” Box Office, 1967, p5; “Rising Skepticism on Stars,” Variety, May 15, 1968, p1; “Big Rental Films of 1968,” Variety, January 8, 1969, p15; “Garner Weaver Set,” Variety, March 26, 1969, p7; “20-Acre Set Prepared for Jolly Pink Jungle,” Box Office, July 24, 1969, p9; “Garner Kennedy Re-Team in Co-Prod for UA,” Variety, June 10, 1970, p4; “WB-TV Dealt Stake in Garner Series for NBC,” Variety, August 5, 1970, p28.

Interesting article. No surprise as I was never fond of him in any main roles and always avoided them. First saw him in Shootup at Medicine Bend with Randolph Scott and in The Great Escape. I sensed he was promoted around the time Rock Hudson began to fade out.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He was certainly seen as the next Rock Hudson, to the extent of a couple of movies with Doris Day. I like him more now than I did at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By the time I got into Garner, Rockford was already a hit, so there was never any sense of his struggle as a leading man; he just seemed to have been featured in some big movies. Interesting to read; it’s the perennial struggle to control a career.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating to follow careers. Few go in a straight line, either up or done. In retrospect, they always seem more straightforward than they actually were.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting timeline here of Garner’s rocky road to Rockford.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Many people only know him from Rockford. One of the few movie stars to make a successful transition to TV.

LikeLiked by 2 people