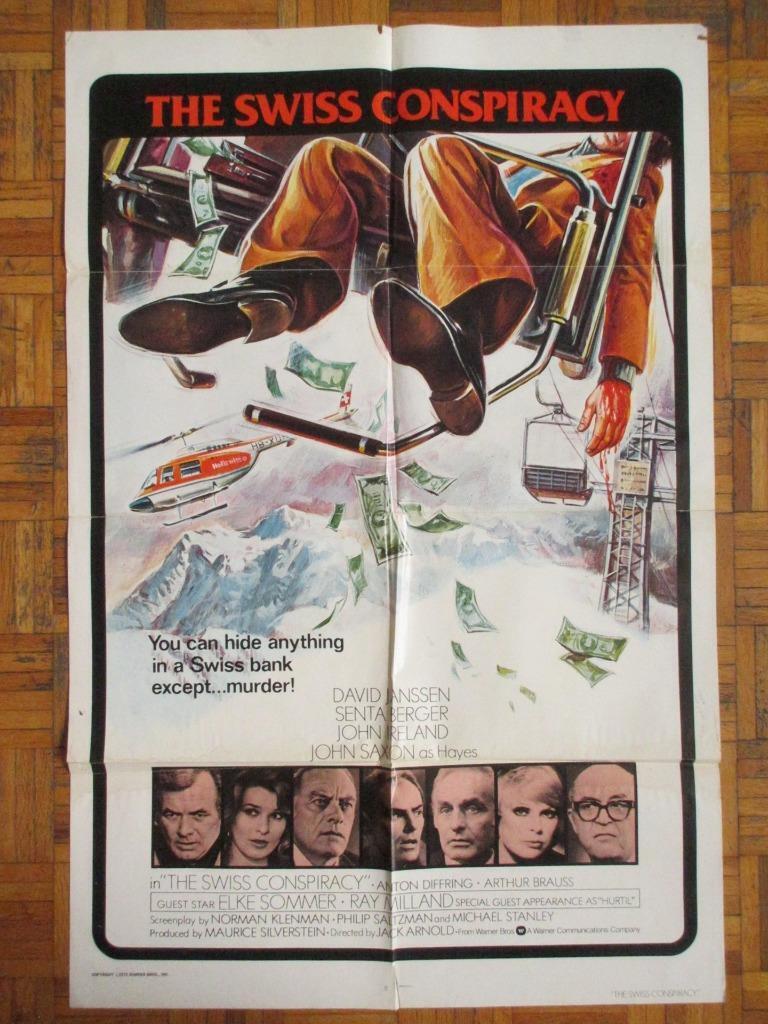

Not an obvious candidate for a Behind the Scenes feature, but important for four reasons. It ushered in the sub-genre of financial thriller, raised issues about tax-shelter funding, brought Hollywood back into European financing and was another example of how desperate the industry was for product that it would fund new entries from untried producers.

Banks were rarely a subject matter for movies except as the object of a heist or if they were foreclosing on a poor farmer or business, but former banker Paul Erdman, who had written his thesis on Swiss banks and the Nazis, single-handedly created substantial interest with a series of thrillers exposing the business. The Billion Dollar Sure Thing was a 1973 bestseller, as was the following year’s The Silver Bears. The latter, filmed in 1977 with Michael Caine, was beaten to the punch by The Swiss Conspiracy, an original screenplay.

Making acerbic comment about money has become critically-applauded big business ever since. Think Alan J. Pakula’s Rollover (1981) with Jane Fonda and Kris Kristofferson, Michael Douglas’s Oscar-winning role in Wall Street (1987), Oscar-nominated The Wolf of Wall St (2013) and The Big Short (2015) and more recently Dumb Money (2023). Hardly so successful or lauded, The Swiss Conspiracy nonetheless started a trend.

In the mid-1970s, cinemas were clamoring for product. Despite gigantic hits like The Godfather (1971), The Sting (1973) and The Towering Inferno (1974) – and with Jaws (1975) on the horizon – studios had not returned to the production levels of the 1960s never mind the golden days of the previous decades. Cinemas had made do with cheap fillers, blaxploitation, sexploitation, four-walled nature documentaries, and kung fu. But with such an obvious gap to be filled, it was relatively easy for new producers to seduce banks and other investors into backing new pictures.

Raymond Homer had come from film processing. He had been a laboratory chief before moving into production. He set up his Durham Productions with the aim of exploiting opportunities for cheap moviemaking in South Africa. For The Swiss Conspiracy He partnered with former distributor Maurice “Red” Silverstein and the German producer Lutz Hengst (King, Queen, Knave, 1972) and Warner Brothers.

This proved part of a major development for the Hollywood studio which, like most of its breed, had either pulled out of funding European movies entirely or continued on nothing like the scale of the previous decade. The cutbacks were as much to do with ongoing financial fears as the losses engendered in European investment during the roadshow splurges of the 1960s.

WB now pursued an “aggressive” European funding policy, setting aside $12 million for investment in 13 pictures. These included the thriller Inside Out (1975) with Telly Savalas and James Mason, Permission to Kill / The Executioner (1975) starring Dirk Bogarde and Ava Gardner, Peter Collinson’s The Sellout (1976) with Oliver Reed and Richard Widmark, Trial by Combat / A Dirty Knight’s Work (1976) toplining John Mills and Barbara Hershey and The Swiss Conspiracy. United Artists and Columbia had also triggered substantial European funding.

Shooting on The Swiss Conspiracy began in May 1975 on location in Switzerland and in the Bavaria Studios in West Germany. The cast was decidedly dicey. David Janssen (The Warning Shot, 1967) had only made one movie in five years. Senta Berger, though still in demand in Europe, had not starred in an American production since The Ambushers (1967). She may even have been cast out of convenience as she lived round the corner from the Munich studio. The other cast members – John Ireland and John Saxon – were either supporting players or like Ray Milland long past their peak.

Co-producer Maurice Silverstein was every bit ambitious as Homer. The next movie on his dance card was intended to be an adaptation of the John Le Carre bestseller A Small Town in Germany. But he was also lining up The Left Hand of the Law with James Mason and Stephen Boyd, Blood Money and The Jumbo Murders.

The Swiss Conspiracy was first released in Britain. In May 1976 it opened in first run at the Warner multiplex in London’s West End, doing so well at the 132-seat Warner 1 it was shifted for the rest of its four-week run to the larger 434-seat Warner 4, for reasonable returns but not enough to win a circuit release in either of the two major chains.

Despite its funding, however, Warner Brothers’ rights did not include the US/Canada. So while the movie went out in Europe in 1976, it took another year to reach America, via distributor S.J. International which released the movie first (minus any kind of premiere or particular fanfare) in Denver in August 1977 across five screens. There was no national saturation release but eventually 400 prints found their way across America between August and December.

The best results in first run were a “tasty” (in Variety parlance) $3,000 from two cinemas in Portland and a “neat” $7,000 in Boston. Otherwise results registered as “dismal,” “dull,” “slow,” “soft” and similar.

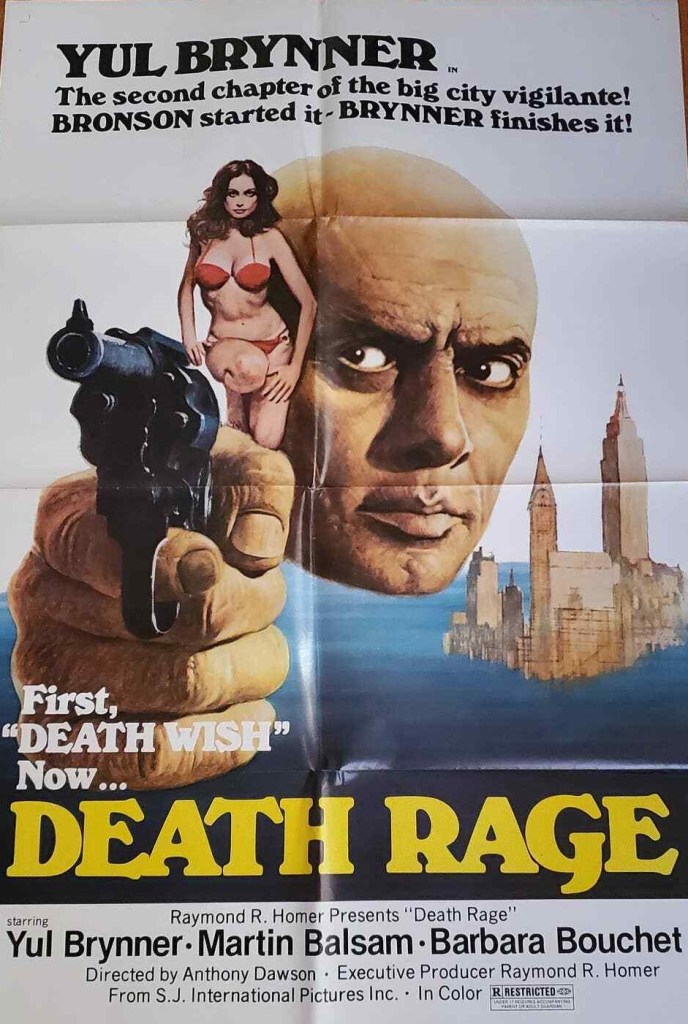

Despite the movie’s less-than-stellar U.S. box office Homer, now considered a fully-fledged producer, announced a slate of eight pictures. Sharpies was set to star Stella Stevens (The Poseidon Adventure, 1972) and Camilla Sparv (Downhill Racer, 1969). The Inheritance was headlined by Anthony Quinn (Guns for San Sebastian, 1968), Shadow Killer by Yul Brynner (Westworld, 1973), For the Love of Anna by British actress Lynne Frederick (Phase IV, 1974), The Naked Sun by Roger Moore (Live and Let Die, 1973), Queen of Diamonds by French star Olga-Georges Picot (Day of the Jackal, 1973) and The Great Day by Sophia Loren (Man of La Mancha, 1972). Compared to The Swiss Conspiracy, these movies had stars with considerable marquee value.

But the wheels came off the nascent production efforts of Homer and Silverstein when they were sued by investors for $45 million. Turned out their productions were in large part funded by a group of mid-West tax shelter investors who had not quite grasped, it would appear, how risky motion picture investment could be.

By and large, the biggest recipients of investor largesse are the cast and crew, followed by the producers, with actual investors last in line to receive any monies. Even if a movie wasn’t a hit, and there were no profits to re-distribute, a producer would still, at the very least, receive a production fee and most likely cream other monies off the top, accommodation, entertainment, transport and the like.

While tax shelter investors were looking to minimize taxes or avoid paying them altogether, they did not expect to see their cash just disappear. One of the big problems for a movie producer was that it was virtually impossible to bury results in the accounts. Box office was too transparent for that. Simply by following the weekly box office reports in Variety or Screen International in Britain you could determine a picture’s performance.

What was soon obvious to the investors was not just that the likes of The Swiss Conspiracy had done poorly, but that some of the other pictures appeared not to have been even released – or made (The Naked Sun, The Great Day, Sharpies). And that attempts to secure releases were limited by the lack of trade showings (only one in New York, for example), those being the most direct way, screening the picture to potential buyers, to secure bookings. The result of that being that none of the slate received any New York bookings.

Variety commented: “Such U.S. funded films seem to disappear almost completely here after appearing initially in the production charts.”

And eventually the sad tale that did emerge was how easily investors were duped by the thought of instant riches and just how tricky it was, even in a product-starved business, for movies produced by unknowns to gain any traction, and that names (emblazoned across full-page advertisements in Variety’s bumper Cannes editions, for example) that seemed to scream box office potential would struggle to deliver without distribution.

Turned out Raymond Homer did have a strategy, or he evolved one, though not one that would have enticed initial investors. Homer stated that he expected his main source of revenue to come from outright European sales and television and cable in the U.S. In theory, this was a sensible approach. Sell a picture outright country-by-country and you avoided the further expense of advertising and distribution. You could reap a reward without further risk and even if those returns were relatively small the cumulative effect might be profit. Joseph E. Levine would become the poster boy for such an approach – his A Bridge Too Far (1977) was in profit before filming began but then he had a top-line all-star-cast and, critically, received the cash in advance.

Theoretically, you could make money if you sold your picture outright country-by-country but only if you had box office figures somewhere to justify the amount you were asking. Homer estimated that his movies had to gross $3 million in the U.S. just to break even and that seemed unlikely so he planned to sell them off to television and cable. But again, sums handed over by small-screen buyers depended also on box office.

The producers encountered myriad problems. Sharpies was not completed due to lack of funds. The Inheritance, for which Dominique Sanda had been named Best Actress at Cannes, found an Italian distributor. After losing 18 minutes for U.S. release and with the addition of a new prolog, it was handled in the U.S. by S.J. International and of all the films seems to have achieved the widest release.

Queen of Diamonds, also directed by Homer, was acquired for U.S. release by Peppercorn-Wormser Inc and while receiving some European exposure was actually made with television in mind as a six-part series. Shadow Killer, renamed Blood Rage, received a very limited released – just 200 prints – in the U.S. in 1978. For the Love of Anna was reshot and released in the U.S. as Until Tomorrow in 1977 and acquired for Japanese release.

None of Silverstein’s planned productions saw the light of day. Homer produced one more picture, Mister Deathman (1983) starring David Broadnax and Stella Stevens, which may have been a re-edited and re-shot version of Sharpies.

On the other hand, the financial thriller became a sub-genre and tax shelters became a major source of funding for movies.

SOURCES: “Silverstein Bows As Conspiracy Producer,” Variety, April 30, 1975, p27; “Swiss Conspiracy Begins Shooting,” Variety, May 28, 1975, p33; “Maurice Silverstein To Produce 2nd film,” Variety, June 25, 1975, p37; “Warner Bros,” Box Office, October 6, 1975, pMC2; “Leider’s O’Seas Dozen for Warners,” Variety, October 10, 1975, p3; “Swiss Conspiracy Rights Acquired,” Box Office, February 7, 1977, p9; “Doctoring For Pics for U.S. Public,” Variety, May 17, 1978, p9; “Raymond Homer Durham Co. Schedules 8 Features,” Box Office, May 30, 1977, p5; “Swiss Conspiracy Bows in Denver,” Box Office, July 4, 1978, p8; “9 Tax Shelter Pix Face Legal Autopsy,” Variety, September 17, 1080, p5; Box office figures for The Swiss Conspiracy drawn from Screen International May 29, 1976-June 26, 1976 and from Variety in various issues August-December 1978.

I’m not a fan of films that start with a list of Belgian tax shelters. In general, films made through this kind of arrangement aren’t great, as I think some of the titles featured in your admirably reserach article suggests…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hiding money form the taxman and then losing it, it’s fair world after all. Although I think any losses counted against tax. So it was win-win.

LikeLiked by 1 person