Assessing foreign potential was a dicey business. A decent run abroad could save a picture or at least ease the bottom line. But global box office statistics were not as easily generated or understood as now. As in the U.S., television had sapped the cinema-going habit in other countries, variations in exchange rates could cripple revenue expectation, and most countries imposed some limitation on the importation of Hollywood films.

It would have been a very bold industry analyst who predicted exactly how any film – even a big U.S. hit like The Sound of Music (1965) – would perform on foreign screens. In the previous article, I was able to assess the results for 107 movies, but the sources for overseas revenues are more limited and figures, using the Aubrey Solomon digest, are only available for 49 of those

The good news, I would guess, is that 14 pictures released by Twentieth Century Fox improved on their U.S. rentals. One (The Sweet Ride, 1968) did exactly the same business abroad as at home. On the gloomier side, 34 movies did worse. For movies that had already turned a profit on home territory, any extra revenue from overseas would be viewed as icing on the cake. But for movies that had struggled or been outright flops on U.S. release, foreign distribution offered an opportunity to correct the financial imbalance.

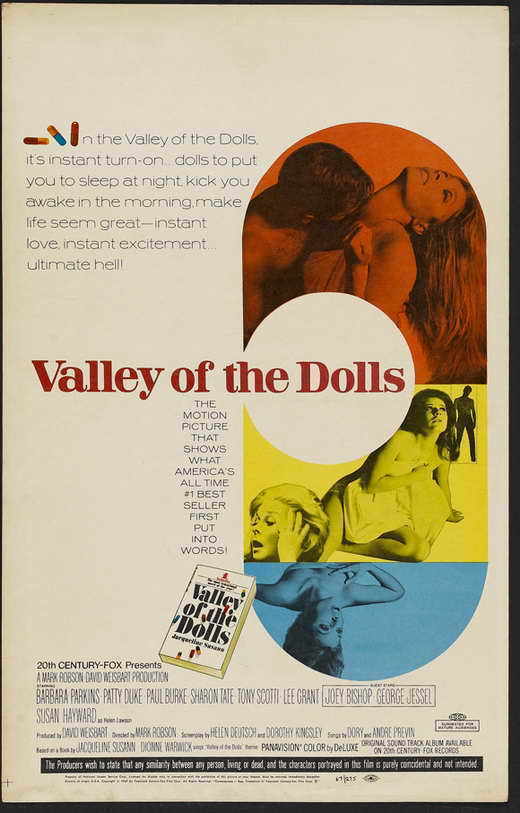

And anyone trying to forecast the outcomes would have very little chance of getting any correct. How can you come to terms with a business where Doctor Dolittle (1967) one of the biggest flops of the decade on home soil turned into one of the biggest hits of the decade in foreign cinemas. Or that one of the biggest U.S. hits of the decade, Valley of the Dolls (1967), managed to generate a fraction of the rentals received at home. In terms of failing to match up to expectation you could only categorize its overseas performance as a flop.

No surprises for guessing that the studio’s biggest hit overseas was The Sound of Music. What did take the industry’s breath away was that the move came nowhere near matching its U.S. results. The $37.6 million in rentals was less than a third of the amount taken at home. Valley of the Dolls, a juggernaut at home with $20 million, brought in a paltry $2.92 overseas. Other domestic big hitters to come nowhere near emulating their domestic results were: Planet of the Apes (1968), $5.8 million overseas, $15 million at home; The Sand Pebbles (1966), $7.1 million overseas, $13.5 million at home; The Bible (1966), $8.35 million overseas, $15 million at home; and The Boston Strangler (1968), $3.12 million overseas, $8 million at home.

Against all expectations given the size of its failure in the U.S., just $6.2 million in rentals on a budget of $17 million, Doctor Dolittle knocked up $10.1 million abroad. World War One picture The Blue Max (1966) also astonished, $8.5 million overseas (where it often qualified as a roadshow) compared to $8.4 million at home.

By comparison another roadshow, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965), improved on its U.S. figures, producing $15.9 million overseas against $14 million at home. Audrey Hepburn was a bigger star overseas than in the U.S. which went some way to correcting the disappointing rentals incurred Stateside by How to Steal a Million (1966) and Two for the Road (1967). The former took $6.05 million on foreign screens compared to $4.4 million at home and the latter $4.3 million compared to $3 million at home.

Other films for whom foreign was better than domestic included: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969) – $3.65 million vs $3 million; The Chairman / The Most Dangerous Man in the World (1969) – $2.92 million vs $2.5 million; Caprice (1967) – $2.58 million vs $2 million (conversely for Do Not Disturb, 1965, it was $1.27 million vs $4 million); The Flim Flam Man / One Born Every Minute (1967) – $2.32 million vs $1.2 million; Batman (1966) – $2.1 million vs $1.8 million; and The Magus (1968) – $1.45 million vs $1 million.

While not beating their American scores, a number of films achieved quite decent results abroad. For Our Man Flint (1966) foreign attracted rentals of $5.7 million vs $7.2 million in the U.S; In Like Flint (1967) $4.12 million vs $5 million; and The Undefeated (1969) – $4.27 million vs $4.5 million.

Some of the biggest flops on the U.S. domestic scene had no chance of redemption abroad. Possibly their Stateside performances put off distributors in foreign countries. Despite Richard Burton and Rex Harrison, Staircase (1969) earned only $360,000 abroad. George Cukor’s Justine (1969) managed only $570,000. James Stewart comedy Dear Brigitte picked up only $720,000. Tony Curtis-Debbie Reynolds romantic comedy Goodbye Charlie (1964) ended with $800,000. Shirley MacLaine comedy John Goldfarb, Please Come Home was limited to $880,000. Robert Aldrich’s Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte starring Bette Davis and Olivia De Havilland was a complete misfire – $4 million rentals at home, less than $1 million abroad.

Just as at home, Frank Sinatra was a relatively safe bet. Von Ryan’s Express (1965) brought in a further $6.27 million abroad to add to the $7.7 million coughed up in rentals by U.S. cinemas. The Detective (1968) added another $3.77 million from foreign ticket wickets compared to $6.5 million at home. Tony Rome (1967) brought in another $2.25 million to add to the existing $4 million.

Raquel Welch had more admirers abroad than at home. Foreign results for controversial western 100 Rifles (1969) nearly match domestic income, $3.4 million vs $3.5 million. Fathom (1967) out-earned domestic, $2.27 million overseas against $1 million at home. Bandolero (1968) pulled in $3.3 million vs $5.5 million. Fantastic Voyage (1966) slammed home another $3.38 million on top of $5.5 million at home. Bedazzled (1967), which only cost Fox $770,000, brought in $1.32 million abroad and $1.5 million at home.

Note: my two sources shown below, while presumably using the same figures, used them in different ways. Solomon employed only domestic rentals (and excluded I would guess pictures for which Fox acted more as the distributor than the maker) while Silverman took a global rental approach so it was down to me to subtract domestic from global to unravel foreign rentals. Any mistakes, of course, are mine.

SOURCES: Stephen M. Silverman, The Fox That Got Away, The Last Days of the Zanuck Dynasty at Twentieth Century Fox (Lyle Stuart Inc, 1988) pp323-328; Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century Fox, A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Press, 2002) pp 228-231, 252-256.