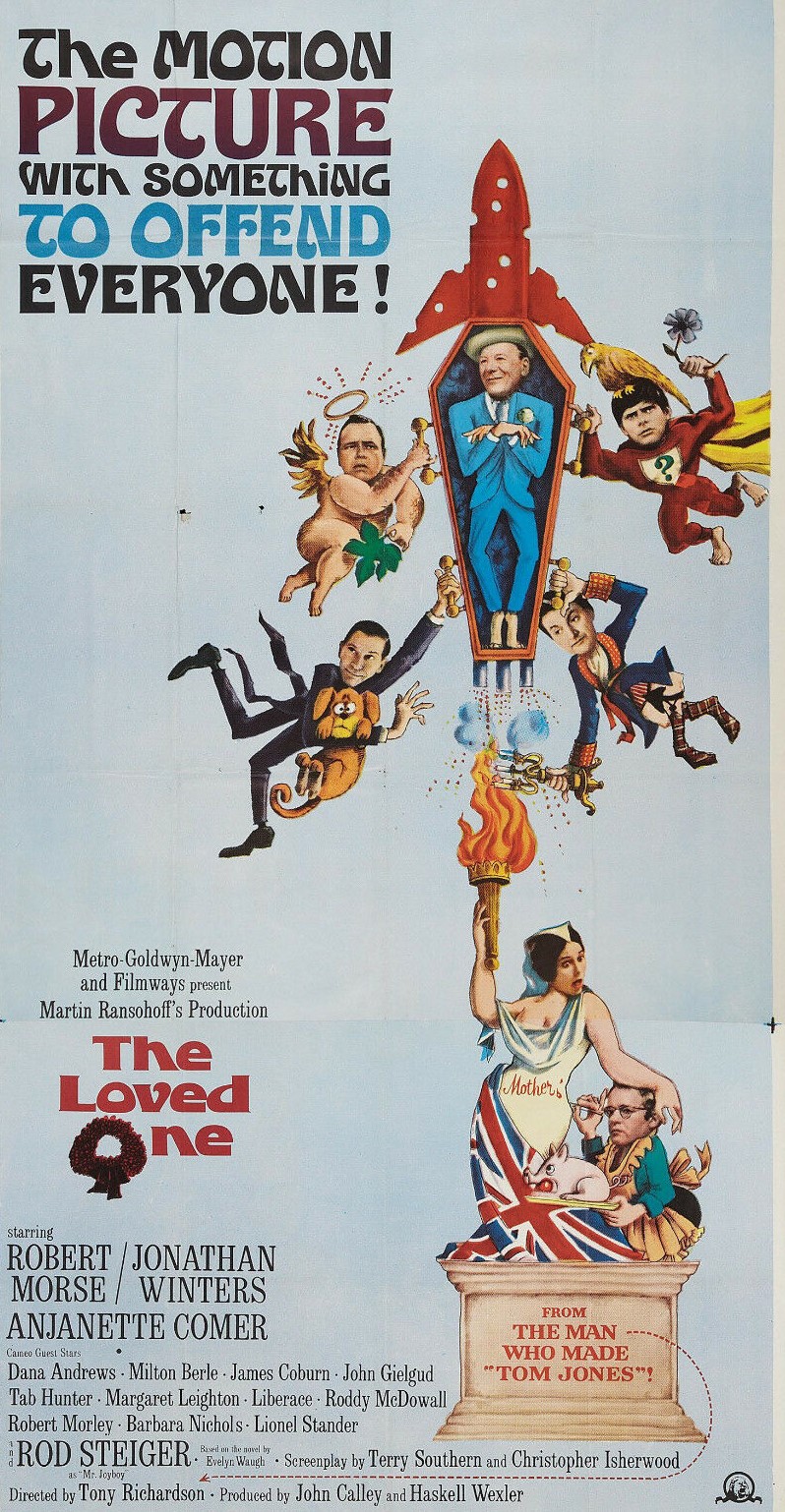

Yep, you hand the promotional department the problem of selling a movie about undertakers and see what they come up with. The tagline “the motion picture with someone to offend everyone” is unlikely to attract the unwary and leaves you only with an audience that enjoys seeing sacred cows slaughtered, which might minimize appeal. Coupled with a montage of outlandish scenes and characters, the main advert had its work cut out to attract anyone.

Just as well, then, the marketing department had some apparent plums up its sleeve. Even more than weddings, funerals are associated with flowers. So, top of “the ticket-selling ideas” was suggesting to cinema owners either to stick a wreath at the front door or get a florist to spell out the title in a lobby display.

If that didn’t work, go for broke and stick a tombstone (easily constructed from plywood or papier mache, apparently) in the lobby. (The Fall of the House of Usher had gone one better, promising a free casket to anyone who dropped ad of fright.) Better still, lay down grass on the pavement outside to achieve a lawn effect.

And if that doesn’t get the media buzzing, why not just hire a hearse. That could sit outside the theater or tour the locality with banners slung along the sides. If the local newspaper was willing, you could arrange to have the print delivered by hearse, photographer on hand to record proceedings.

“Since The Loved One spoofs the undertaking business, most morticians aren’t too happy with the picture. This can be twisted to advantage to get you a newspaper story,” proclaims the Pressbook. Basically, the notion is that undertakers will respond to a reporter nosing around and that somehow that will permit mention in the resulting article of the movie. Another idea is to invite undertakers to the opening night on the assumption that no one will turn up and that somehow that, too, will make a newspaper story.

A simpler alternative was just to hire a model and have her parade around town dressed in white like a mortician and passing out flowers.

Just in case nobody had noted the off-beat nature of the picture, cinema managers were encouraged to browbeat local journalists into spelling this out and putting the movie into the same bracket as Dr Strangelove (1964), What’s New, Pussycat? (1965) and, of course, Tom Jones (1963).

Oddly enough, the movie received a favourable press – or at least a word or two which could be culled from reviews to make it appear so. Thus, one advert was able to rustle up quotes from the New York Times, Cue magazine, Herald Tribune, Holiday magazine, Life and Saturday Review.

Basically, there was as little meat on the advertising bones as in the genuine narrative to the picture itself. There was only one tagline and all the adverts, covering three-quarters of the 12-page A3 Pressbook, were variations on the one ad.

Outside of the cameo appearances, the male and female leads were relative newcomers, both starring in Quick, Before It Melts (1964). Courtesy of his long-running role on Broadway hit How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, Morse was marginally the bigger marquee name.

For a comedy, it was a potentially lethal role for Morse. “There was one scene in which a toy rocket blew up in my face and another in which I was dragged 40 feet by an automobile. I came close to being asphyxiated after doing a 60-minute stint in an air-tight embalming room.”

“Fate has been kind to me so far,” averred Comer. “But it didn’t all happen overnight, you know. Actually, I don’t think the quickie successes mean very much. You can be belle of the ball one day and a has-been the next.

“When I decided to go into this business, I made up my mind about one thing. I wouldn’t go into it unprepared. I got the groundwork in workshop plays at the Pasadena Playhouse and I concentrated on acting to the exclusion of everything else. I never even got to see what Hollywood actually looked like.”

After the success of Tom Jones, director Tony Richardson was given carte blanche. He filmed in 21 locations including the California freeway (as yet unopened), pet cemeteries and Beverly Hills mansions (the ground floor of Dohney marble chateau) and never in the studio. “I feel constricted working anywhere but in the real locales,” he told the Pressbook. “There are inconveniences in working outside a studio but I don’t mind them.”

His quest for realism extended to make-up. For example, he vetoed applying make-up to Jonathan Winters’ hand so that it matched his tanned face. Other attempts at verisimilitude saw lights taped to ceilings and sound equipment strapped to plumbing. Substitutes were found for equipment deemed too bulky or sensitive for location filming.

Future Warner Bros boss John Calley, here working as co-producer, explained some of the problems encountered. “Normally, when a piece of equipment is to be used or something needs to be constructed in Hollywood, it is only a matter of dialling the proper studio telephone extension. But under the Richardson plan every bit of equipment, every prop, every item of construction had to be individually contracted. There is no question that this is the most difficult way to make a picture, but it is the only way Richardson will work.”

John Calley doesn’t sound to thrilled about Richardson if you read between the lines.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That came across loud and clear. Couched somewhat diplomatically for the Pressbook.

LikeLike