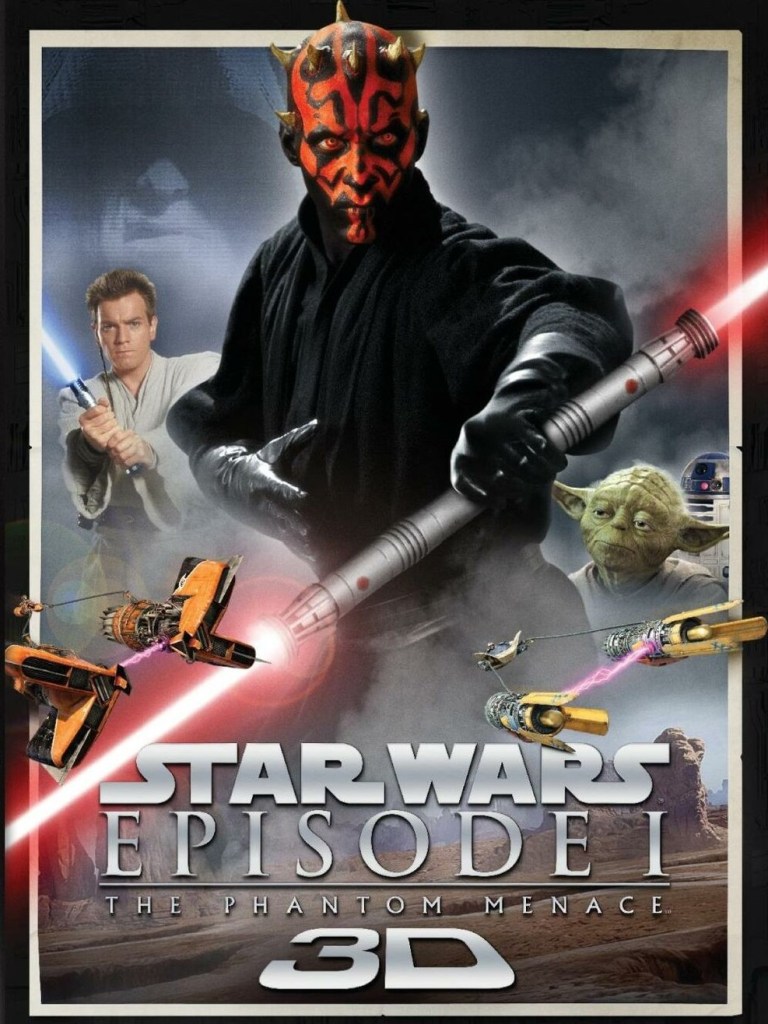

Astonishment all round from box office aficionados that the reissue of Star Wars I: The Phantom Menace (1999) has done so well at the weekend’s pack ($8.1 million gross – enough for second place). But that’s because most people don’t realize that the reissue in general has been around for well over a century, ready to step in to plug gaps (as now) in the product pipeline.

In fact, the original Star Wars (1977) – Episode IV: A New Hope – triggered a new style of reissue in 1978. The reissue had been reinvented several times over already, appearing under such nom de plumes as “revival,” “encore triumph” (“double encore” for a double bill), “masterpeice reprint,” before finally emerging as a genuine restoration, or re-released in 3D or Imax. Prior to the 1970s, studios had generally allowed box office hits to stick around the vaults for a decade or so – the idea they were re-released every seven years, theoretically long enough for a new generation to spring up, is a misconception.

Gone with the Wind appeared twice in the 1960s, the last time revived as a 70mm roadshow. And studios had taken to rushing out double bills of big hits – any configuration of James Bond pictures, for example, plus Bonnie and Clyde/Bullitt, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid/The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

But the Star Wars revival in 1978 took the reissue to a new level. For a start, Twentieth Century Fox had invented a new word for it. They called it a “wind-up saturation.” They could call it anything they liked after what the box office engendered in the first week. With a $2 million advertising campaign and merchandizing that included bed sheets and sleeping bags, and opening on 1750 screens, Star Wars not only shattered the weekend box office record for a reissue it clobbered the record for a new film currrently held by Jaws 2.

After pulverizing the opposition with $10.1 million in the first weekend, it went on to rack up $45 million, a remarkable $24 million of which was rentals (meaning the studio was generally demanding a 60/40 share of the box office). So now reissue was seen as a clever method of bringing a new release, more than a year later, to a resounding close. There wasn’t time for anyone to get nostalgic about an old picture, the studio just rammed it down exhibitor’s throats before anyone could tire of it.

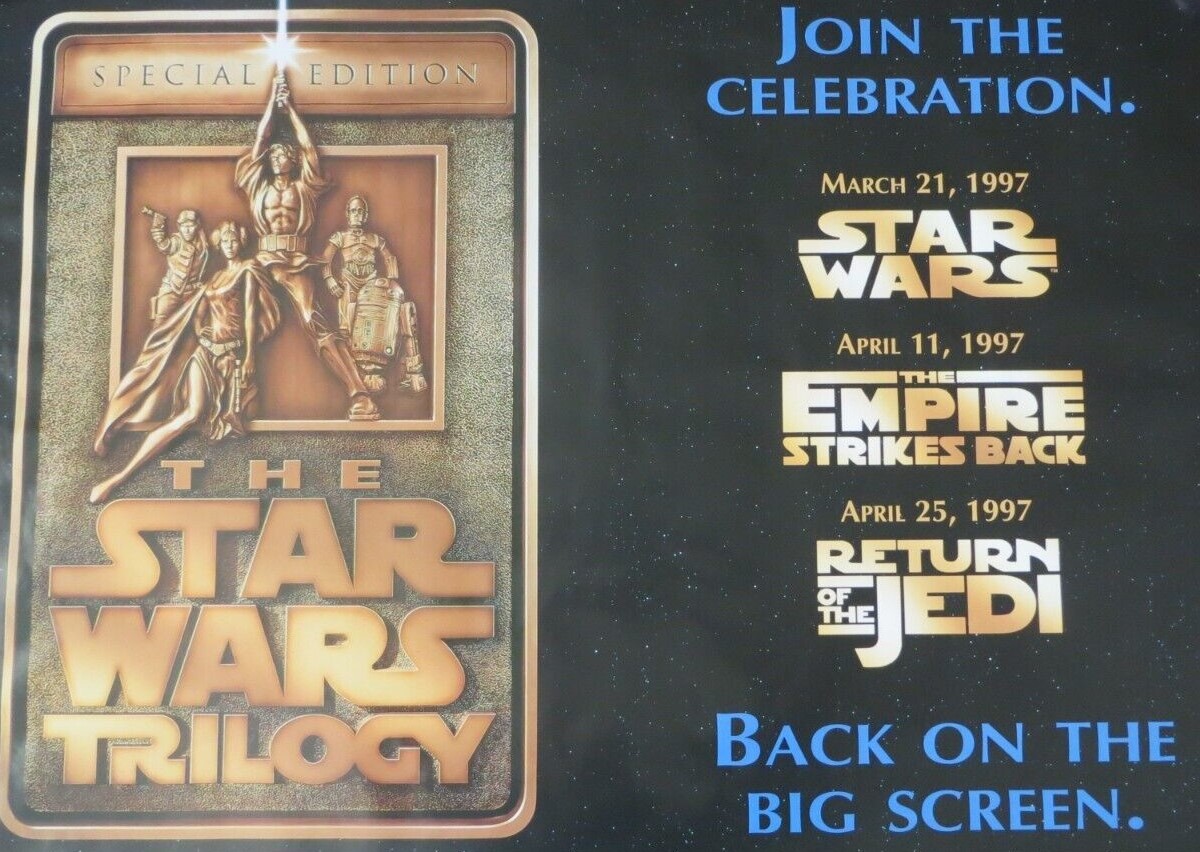

The Empire Strikes Back added another near $20 million in the two years after its initial release while Star Wars kept chugging along, another $9.3 million in 1981 and $8.3 million in 1982. But this was a gold mine that kept giving and, in 1997, following the Hitchcock reissue template of 1983, Fox brought back the first trilogy as the theatrical equivalent of a box set, releasing them three weeks apart. This was despite an actual video box set of the trilogy selling 22 million copies. But there were already 350 websites devoted to a galaxy far far away (a massive number in the prehistoric days of the internet).

Fox gambled there were two generations (using the old seven-year-cycle idea) that hadn’t seen the first picture on the big screen. There was also the opportunity for artistic reassessment and Fox spent $10 million on the restoration of the first picture, the sequels half that again each. In the first place, the negative had suffered considerable deterioration and then there were the hundreds of visual effects that George Lucas had neither the time nor money to do as effectively as he wished. Around a third of the budget went on audio. Lucas described it as “a rare chance to fix a movie only 60 per cent right.” So it qualified as a “Special Edition.”

Lucas viewed the trilogy as a serial unfolding in successive weeks. At its most basic, it was an exercise in nostalgia for fans too young to understand the meaning of the word. In reissue terms, it was the biggest, splashiest event of all time, better even than MGM’s 70mm reinvention of Gone with the Wind or David Lean’s restoration of Lawrence of Arabia. Excitement reached fever pitch. Only 2,000 screens were given the opportunity to make potential reissue box office history, Fox again setting stiff terms. Star Wars grossed another $138 million, The Empire Strikes Back $67 million and Return of the Jedi $45 million, the only sour note being the argument that if they had spaced the films out they might have done even better.

But when the time came to bring back Phantom Menace, there was a new toy to spark life into old pictures. 3D had been reinvented to accommodate reissues. Disney had made the running here, snacking on $30 million for a double bill of Toy Story/Toy Story 2, $98 million for The Lion King and $47 million for Beauty and the Beast. In 2012 the 3D version of The Phantom Menace romped home with a $43 million pot.

By such standards, this weekend’s reissue is strictly small potatoes, though proof that old movies never die and that nostalgia lives to fight another day.

SOURCE: Brian Hannan, Coming Back to a Theater Near You, A History of Hollywood Reissues 1914-2014 (McFarland, 2016), 274, 283, 286, 287, 289, 290, 291, 298, 304, 312, 313, 320, 329.