Charlton Heston started the 1960s if not as the biggest star in the world then at least the star of the biggest film in the world, Ben-Hur, released in the last month of the previous year, and ushering in the roadshow era. One of eleven Oscar winners for the picture, Heston’s career was at all-time high. While he wouldn’t ever enter the Steve McQueen/Robert Redford universe of being offered every conceivable script, he was still a huge marquee draw. And it’s interesting to see not so much just what he chose but what he rejected and why.

Often an automatic choice for epics in the vein of El Cid (1961), 55 Days at Peking (1963), The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) and Khartoum (1966), he was versatile enough to play in westerns like Major Dundee (1965) and Will Penny (1967), ground-breaking sci fi Planet of the Apes (1968), war Counterpoint (1967), drama Number One (1969) and even leave room for some comedy The Pigeon That Took Rome (1962). When you were as big as Heston, you had choice and could vary your projects.

In 1960 while dithering over a poor screenplay for El Cid, Heston turned down By Love Possessed (1961) made by John Sturges, and From the Terrace (1960) which Mark Robson filmed with Paul Newman. Heston’s judgement was that both scripts were inferior to even what was currently being put before him for El Cid. While the Sturges flopped, the Robson did well.

The next year Samuel Bronston, producer of El Cid – and later 55 Days at Peking – attempted to tie Heston down to a picture about William the Conqueror and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Nicholas Ray, who would direct Heston in 55 Days at Peking, wanted him for a picture about the Children’s Crusade. Twentieth Century Fox offered him a three-picture deal, beginning with western The Comancheros (1961). Heston “was leery” and rejected the project – and the overall deal – when the directors Fox initially suggested were too “routine” for Heston’s taste. Presumably, neither was legendary Warner director Michael Curtiz who made the picture with John Wayne.

Heston felt “a slight pang of guilt” turning down the opportunity to work with Laurence Olivier on an adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory because while it would receive cinematic distribution abroad it would be shown on television in the U.S. That went ahead with Olivier and Frank Conroy in the Heston role but with very limited overseas distribution.

He was very keen on Otto Preminger’s Advise and Consent (1962). It appealed “without reading the script.” However, he was offered the part of Brig Anderson, which he disliked. “I’m not put off by the homosexual angle,” he confided to his Journal, “but the part isn’t very interesting.” He pushed for Senator Cooley but Preminger was already chasing Spencer Tracy for that role and, when he passed, happy with second choice Charles Laughton.

Heston dithered over Easter Dinner because he didn’t want to work in Rome. Director Melville Shavelson suggested filming in Paris with Charles Boyer or Maurice Chevalier as co-stars. An alternative title was Americans Go Home. It became The Pigeon That Took Rome (1962) but a chunk was filmed on the Paramount lot.

Perhaps the most interesting prospect was a remake of Beau Geste (1939) with Dean Martin and Tony Curtis. Also on the table was The View from the Fortieth Floor from the bestseller by Theodore H. White.

In 1962 he became enamoured of a project he had previously rejected. The Lovers by Leslie Stevens (who would later create The Outer Limits television series) was a Broadway play starring Joanne Woodward in 1956. Heston now envisaged it as an ideal movie vehicle. He would spend the next few years trying to put it together; it became The War Lord (1965). He turned down a Renaissance film from Arthur Penn (The Chase, 1966), The Royal Hunt of the Sun (1970) and a similar Orson Welles project on Cortez (never made).

In 1963 he received three scripts in one day. A pair were presented as a two-picture deal from Twentieth Century Fox. While Heston was keen on The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) he was less impressed by Fate Is the Hunter (1964). The other script, from the Mirisch Bros, was The Satan Bug (1965) from the Alistair MacLean thriller, which went ahead with name director John Sturges but no-name star George Maharis. He rejected Lady L (1965) opposite Sophia Loren and Morituri (1965), wryly commenting that Brando “should have passed too.” He was very tempted by a “very funny” script for The Great Race (1965) but “taking it would mean pushing back War Lord again.” Tony Curtis stepped in.

Twentieth Century Fox was pushing in 1964 for him to become involved in a film about General Custer. He declined. “It doesn’t seem like a good idea to me.” He also turned down Hawaii (1966) “with a few regrets, it has too much plot and not enough people.”

In 1965, another Alistair MacLean project came his way with Ice Station Zebra (1968). “Good script but I don’t like the part.” He was also offered a “curious comedy” Twinkle, Twinkle, Killer Kane by unknown William Peter Blatty, later author of The Exorcist (1973). This was filmed as The Ninth Configuration (1990), directed by the author. He mulled over Sam Peckinpah script Hilo (never made), an unnamed Mirisch western, The Quiller Memorandum (1966) – “modern story and a simple part” – and The Way West (1967). A second effort was made to enrol him for the Beau Geste (1966) remake with him playing the sadistic sergeant.

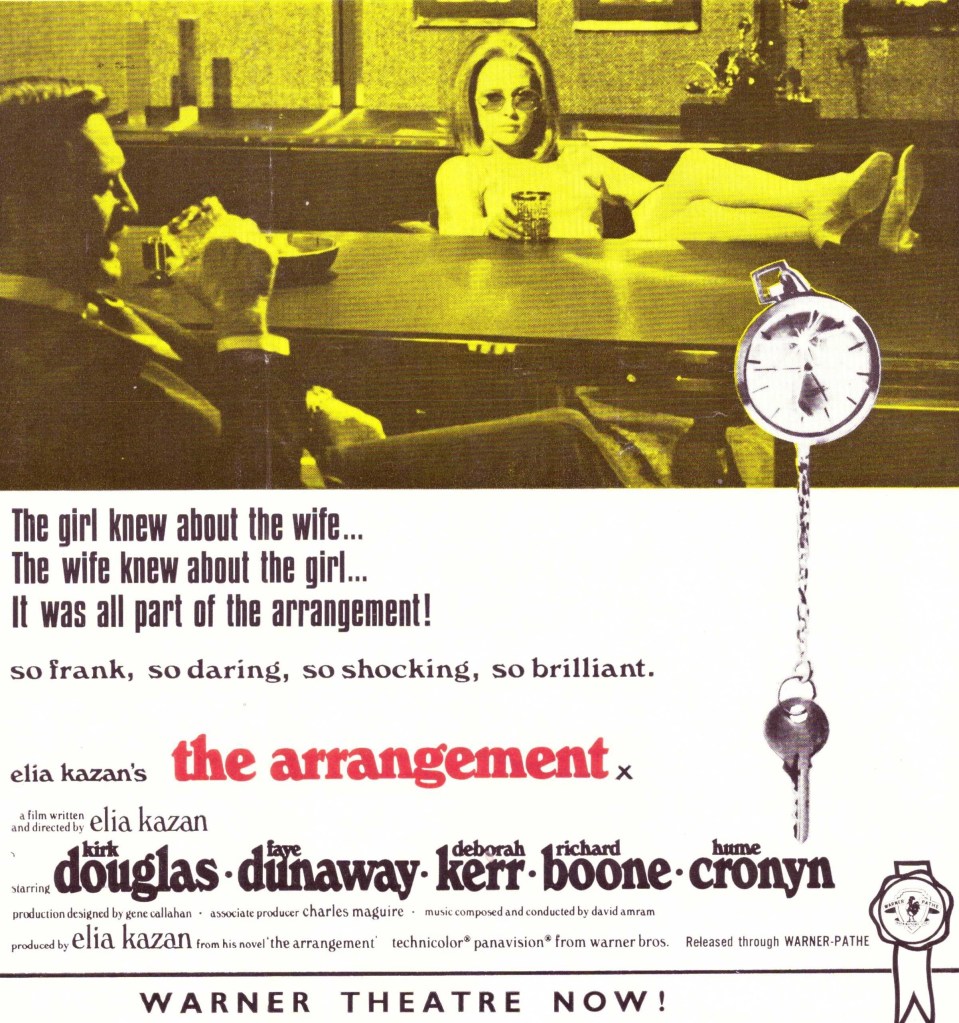

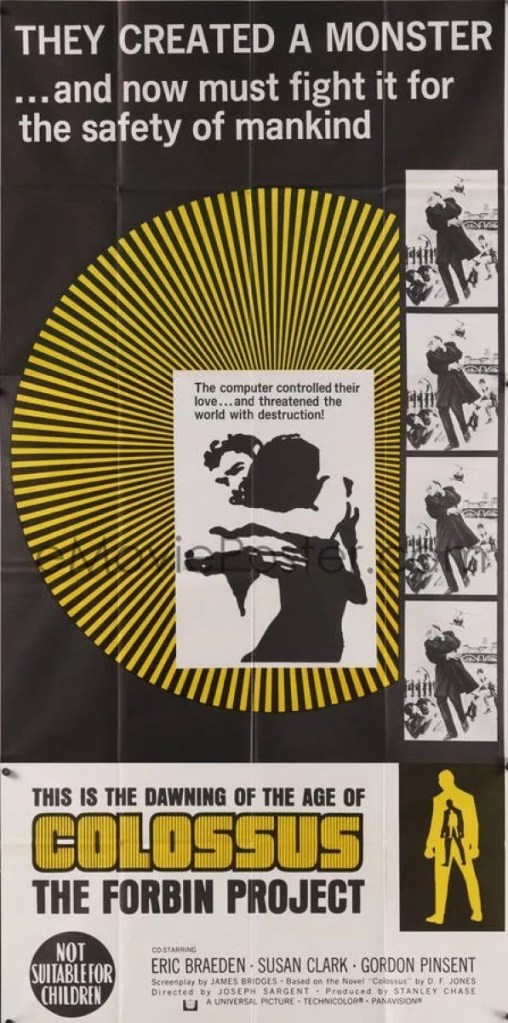

Vittorio De Sica came calling in 1966 for a film with Shirley MacLaine Woman Times Seven (1967). He was “flattered to be asked” to star in Heaven’s My Destination to be directed by Garson Kanin based on the bestseller by Thornton Wilder. There was short-lived attempt in 1968 to mount Eagle at Escambray to be directed by Sandy Mackendrick. He turned down Elia Kazan’s The Arrangement (1969) – “don’t care for it…loser for a protagonist” – Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), a science fiction picture about a giant computer, and a western by Elliott Silverstein (Cat Ballou, 1965) called The Marauders.

Beyond The Great Race and perhaps Hawaii, unlike some stars – come in Steve McQueen and Robert Redford – he doesn’t appear to have turned down anything that subsequently became a major commercial or critical hit.

SOURCE: Charlton Heston, The Actor’s Life, Journals 1956-1976 (Penguin, 1979).