Dream Team Number One: Clark Gable and Jean Harlow. This was of course a good 30 years before the movie actually got made. The Horace McCoy novel was purchased in 1935 by MGM as a big-budget project teaming Clark Gable and Jean Harlow. This was despite Variety proclaiming it was “not screen material.” The premature death of Harlow put paid to the idea. Next, actor Wallace Ford (Freaks, 1932) bought it with Broadway in mind. A production was scheduled to open in 1939, but never did.

Dream Team Number Two: Charlie Chaplin and Marilyn Monroe. When the comedian purchased the rights in the early 1950s he intended Marilyn Monroe to play the leading female. Although she was a mere starlet Chaplin had form in building up newcomers. Author McCoy had by that point become an accomplished screenwriter with over 30 credits including Gentleman Jim (1942), film noir Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950) and The Lusty Men (1952) That concept fell by the wayside when Chaplin was effectively banished from America while launching Limelight (1951) in Britain.

It was another 14 years before interest in the novel was revived by screenwriter James Poe, who purchased the rights from the McCoy estate. Although most famous within the trade for being accused of fraudulent behaviour in relation to his screenplay for Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Despite an Oscar for the film he was sued for $250,000. However, he had a sterling body of work including Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), Sanctuary (1960), Lilies of the Field (1963), The Bedford Incident (1965) and Riot (1969) and two other Oscar nominations.

In 1965 he had signed a multi-picture writer-director deal with Columbia. He was either going to make his directorial on The Gambler or They Shoot Horses, Don’t They. It turned out to be the latter. Failing to get the movie off the ground with Columbia or under his own steam, he turned to new studio Palomar, which was a production entity set up by the ABC television network, which bought over his rights as well as his script but kept Poe on as director.

Dream Team Number Three: Faye Dunaway. Yep, one big star, not two. Poe’s screenplay, while not eliminating the male lead, spun on a female star. Dunaway, hot after Bonnie and Clyde (1967), was offered $600,000 to play the role. Mia Farrow was also in contention, for $500,000. The only problem was, the budget could not remotely stretch to that. As helmed by Poe, it was to cost no more than $900,000. The film was scheduled to begin shooting in spring 1968 but a month later the start date shifted to June.

Two relative newcomers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler were brought in as producers to move the project along. Later they would be responsible for such classics as Rocky (1976), The Raging Bull (1980), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and The Irishman (2018), but at this point they had just three pictures under their belt, although that included Point Blank (1967), Their first task: persuade Poe to rewrite the script. They felt the third act needed work with restructuring elsewhere to make the pay-off work.

But Poe, believing his position was sacrosanct, refused to discuss a rewrite. He refused to discuss anything, period, treating the producers as his assistants rather than people with some power within the studio. According to Irwin Winkler, “Poe seemed unaware of the of the normal process of preparation, even though he’d been around movie sets for decades.”

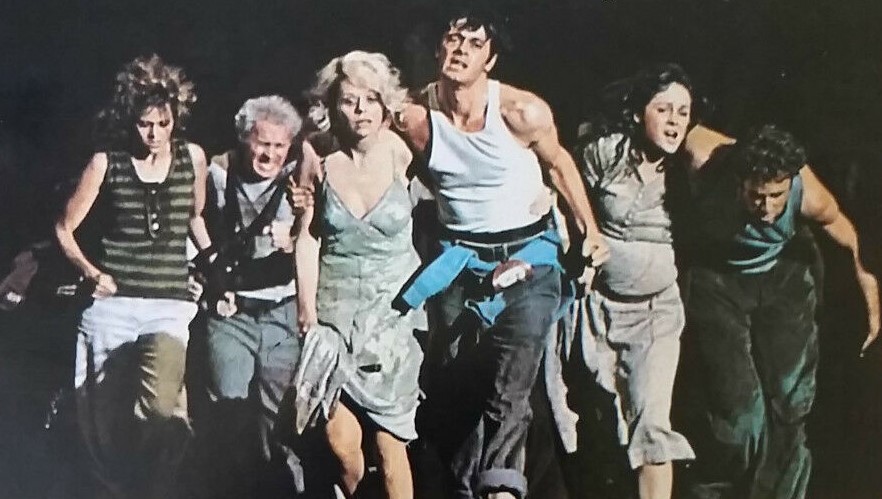

Realising that getting a star on their budget was impossible, Chartoff and Winkler changed tack and talked to good actors, but even then few were interested. A less dramatic star than Jane Fonda you could not imagine, her resume filled with light comedies, French films that utilised her sexuality or the extravaganza that went by the name of Barbarella (1968). But the pregnant Fonda was keen on change. The film was delayed until after she had given birth. Michael Sarrazin should have been out of the equation. John Schlesinger had lined him up for the Jon Voigt role in Midnight Cowboy (1969) but Universal, to whom he was under contract, asked too much to send him out on loan.

With no sign of the rewrites, the producers became antsy about the director. However, they showed their true mettle as producers, convincing Palomar there was no way the original budget would cover the ballroom set, huge number of extras, live orchestra and salaries. It would need to at least triple.

In a picture of one predicament following another, there was one crisis the producers had not foreseen. They were going to be fired. Apart from anything else, they were only executives on the picture with any experience, it being not only Poe’s first movie but that of Chartoff and Winkler’s superiors at the studio. The outcome – the guy who had told the pair they were being fired was shown the door instead.

Susannah York was cast after the producers saw a sneak of The Killing of Sister George (1969) at the Robert Aldrich studios. She had committed to Peter O’Toole vehicle Country Dance/Brotherly Love (1970), written by her cousin James Kennaway (Tunes of Glory, 1960). After too many delays on They Shoot Horses she planned to pull out in favour of the other film. Although Sally Kellerman (Mash, 1970) was set as a last-minute replacement, the issue was resolved by asking MGM to delay the start on the rival picture.

Believing Poe was in no position to helm such a big-budget picture enterprise, Chartoff and Winkler began the process of removing him only for Jane Fonda to dig her heels in. She changed her mind after witnessing first-hand Poe’s directorial skills – or lack of them – when she took part in a screen test for Bonnie Bedelia. Winkler recollected, “On the set Jane asked Poe questions about the blocking of the scene, why she moves in one direction rather than another, why in front of a sofa rather than behind it etc. He couldn’t answer her questions and told her to talk to the cameraman.” Exit Poe.

In terms of a replacement, Chartoff and Winkler set their sights of Sydney Pollack (The Scalphunters, 1968) with whom they had previous dealings, and William Friedkin, then being hailed for The Homecoming (1968) – luckily The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968) had yet to be released. But studio executives had a third director in mind, Jack Smight (No Way to Treat a Lady, 1968). Friedkin should have been in pole position, having only received $75,000 for The Homecoming. His agent, sensing an opportunity, demanded $200,000. Jack Smight’s agent also got greedy and wanted $250,000. Pollack’s agent was happy with the $150,000 on offer.

When Poe was eased out, filming was announced as beginning on February 17, 1969, the budget having now increased to $3.2 million – including $400,000 for extras. However, acoustic issues – seawater had eaten away the bottom of the pier – prevented use of the old Aragon ballroom in Santa Monica. That set was constructed on the Warner lot.

Pollack then turned it down. He had reservations about the script, which had still never been rewritten. When Robert E. Thompson, a television writer but “a Horace McCoy expert,” was mooted, Pollack changed his mind. The new script contained the “flash forward” scenes that prepared audiences for the shock ending. However, the new scenes and delays in starting increased the budget which now ballooned to $4.7 million.

It turned out the director was the best actor of all. “I was impressed with Sydney Pollack’s ease on the set,” recalled Irwin Winkler. “He never seemed to be working hard and yet was able to get marvelous performances out of the actors. Everybody in the company adored him.” Asked by Winkler how he remained so calm dealing with the actors and all the extras and the complicated camera set-ups, he replied, “it was really quite easy.” That same afternoon he collapsed on set and was diagnosed with “nervousness.”

The studio, the stars, the producers, all seemed confident about the picture. All they had to do was convince the audience. But at the first preview in San Francisco the audience roared with laugher at the climactic scene. That shocked the studio to the core until the producers were able to reassure the head honchos that the “fast forwards” would smooth over that problem. Which they did.

It was nominated for nine Oscars – Best Director, Best Screenplay, nods for Jane Fonda, Gig Young and Susannah York among others. Only Gig Young won.

SOURCES: Irwin Winkler, A Life in Movies, (Abrams Press, New York, 2019) p34-47; “Tough Stuff,” Variety, August 7, 1935, p59; “Ford Buys for B’Way,” Variety, September 11, 1939, p42; “Dance Marathon Reprise,” Variety, August 3, 1966, p24; “IT&T In No Way Slowing Down Theatrical Feature Program of ABC,” Variety, January 10, 1968, p4; “Crowded Slate for Palomar,” Variety, February 28, 1968, p18; “Bob Evans Chips-Service To Writers As Stars At Paramount,” Variety, May 1, 1969, p19; “Jane Fonda Gets Top Role in Palomar’s Horses,” Box Office, July 22, 1968, pW1; “Palomar Horses on W7 Space,” Variety, October 23, 1968, p3; “Jan 6 Filming Date for They Shoot Horses,” Box Office, December 16, 1968, pW5; “Cheery Side of Delay on Horses,” Variety, January 15, 1969, p21; “Winkler Wants Films With Social Comment,” Box Office, January 19, 1970, pW1.