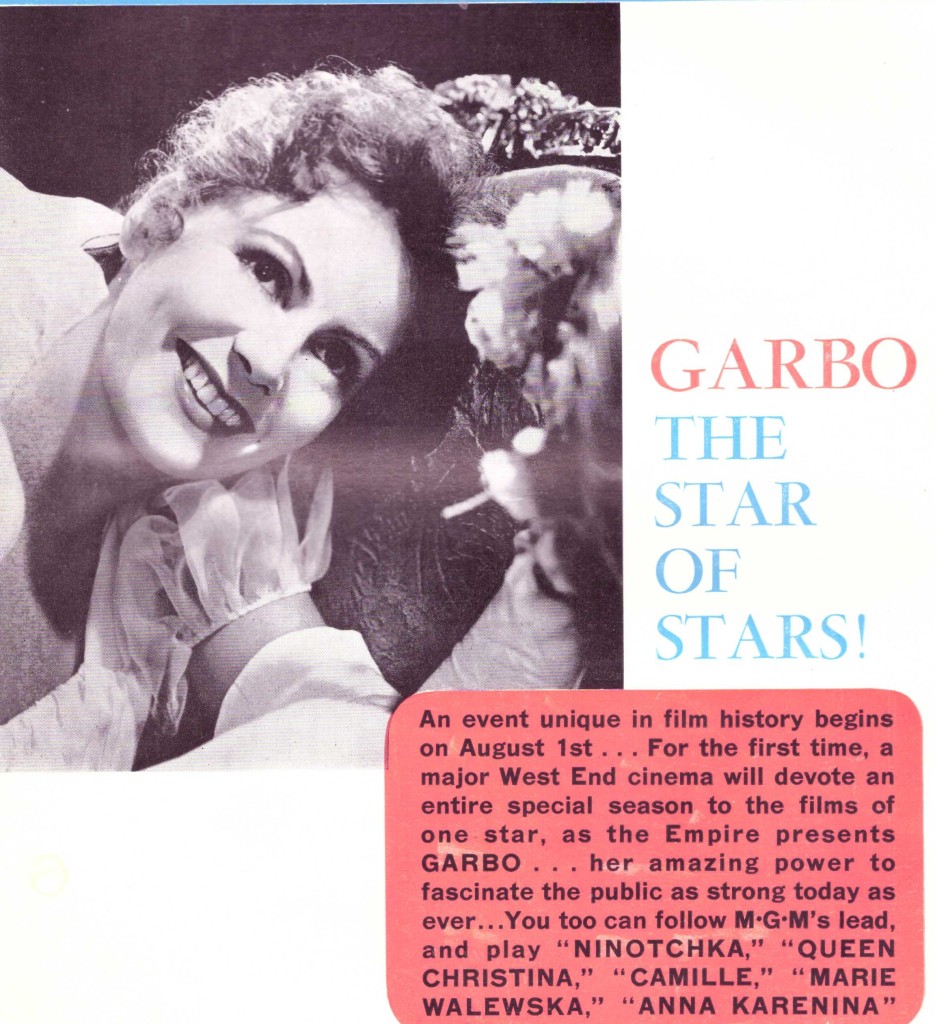

More than two decades after Greta Garbo abandoned acting she was the Queen of London’s West End in one of the most astonishing comebacks in Hollywood history.

Although her Hollywood career was relatively short-lived, lasting only 15 years and ending voluntarily in 1941, and at one point the highest-paid actor (male or female) in Hollywood, the London experience made her a big star all over again in the 1960s – and later in the 1970s – when reissues of her most famous films filled holes in a global release system starved of product.

regarding the words “reissue” or “revival.” And it also suggested a new print since reissues were infamous for re-using long over-used old prints.

She’d first made an impact in the revival business in the U.S. reissue boom of 1948 in a double bill of San Francisco (1936) and Ninotchka (1939), a program so successful that shortly afterwards both were reissued again separately. The box office draw of pictures like these was such that some cinemas, for example, the State in Lubbock, Texas, re-launched themselves as “first run reissue” houses, the beginnings of the boom in repertory theaters.

But it wasn’t all gravy. Distribution didn’t just rely on old prints. Ninotchka, for example, not only had new prints but a new advertising campaign, campaign manual and accessories. However, apart from the first flush of revival, Ninotchka stumbled at the box office, too ambitious a level of release, quickly withdrawn after costing the studio $150,000.

The impetus for the 1960s Garbo Revival came from abroad. In the U.S., Garbo films had by this point been viewed as arthouse fare, running, as in the 1950s, on a repertory basis, rented out for a flat fee, cinemas cramming in as many as a dozen films over one week. While they were available to anyone who wanted them, they came without attendant publicity. Given, they had all been screened on U.S. television they were considered a poor bet for a more commercial revival campaign.

But British television companies, of which there were only two – BBC and ITV – were more niggardly in buying Hollywood pictures so the major studios simply refuse to sell pictures, such as those starring Garbo, at what they saw as, compared to U.S. networks, cut-price rates.

Even so, it was an act of incredible boldness for the Empire cinema in London’s West End, one of the top two theaters (the other being the Odeon Leicester Square) in Britain for movie launches, outside of roadshows, to decide to take a gamble on reviving her movies following audience response to a brief showing at the Royalty. It was the first time a major commercial house in such a heavily-competitive environment had devoted any time to what was in effect a retrospective, setting aside two months for a succession of Garbo pictures.

Two-Faced Woman (1941) – Garbo’s last picture – shored up $14,000 – equivalent to $140,000 now – in its first week. Queen Christina (1937) made a debut of $9,000 and Camille (1936) $11,000. In all, over this opening stint and a further season later on, the Empire screened eleven pictures – the others being Grand Hotel (1932), Anna Christie (1930), Mata Hari (1931), Ninotchka, Anna Karenina (1935), Marie Walewska (aka Conquest, 1937), As You Desire Me (1932) and The Painted Veil (1934)

And there was more to come. The Empire was the release showcase for the entire ABC circuit, so anything screening there would be rolled out in the country’s biggest chain. Since ABC was decidedly not in the arthouse business, sending the movies out into the general mainstream seemed an even bigger risk. But such fears proved unfounded.

Garbo pictures were distributed throughout the country, and not just on the ABC circuit. In Glasgow, for example, the La Scala (owned by Caledonian Associated Cinemas) first-run house – rather than the city’s denoted arthouse the Cosmo – launched a three-week season comprising Ninochka, Queen Christina and Camille, two of the three going out as single bills.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. Garbo movies were being unfurled via the MGM Perpetual Product Plan, whereby classics (rented on a percentage basis) were screened for one day a week for a period of eight-to-ten weeks with audiences able to book a discounted ticket for the entire season. Abroad, there was more opportunity. Like Britain, countries like France revered the star and the movies were continually revived in Europe during the 1960s at commercial venues.

But by the end of the decade, the book should have been closed on Garbo. Because, in 1969, MGM, with the exception of perennials like Gone with the Wind (1939) and Doctor Zhivago (1965), pulled out of the reissue business. The studio withdrew from release its core library of around 100 vintage pictures because the operation was now losing money. Flat fee rentals of $100 (as opposed to the earlier percentage deals) for a three-day engagement failed to cover the costs of prints, distribution and advertising. The novelty of the one-day-a-week scheme had worn off.

MGM intended to try out the old “creating demand” tactic by keeping its oldies out of circulation for at least four years. But the studio was in severe financial straits at the start of the new decade and not in a position to resist an offer in 1970 from Erwin Lesser of Entertainment Events who proposed taking out a two-year lease on 65 pictures that had “made film buffs out of two generations.” Lesser drew up a package of 26 “Movie Incomparables.” Garbo was the main attraction. Included in the list were As You Desire Me, not seen for 30 years. Lesser returned to rentals based on percentages rather than a flat fee.

While Lesser made the movies available as single features and double bills and as support to new features, the main thrust of his marketing campaign was the “Garbo Festival,” an idea stolen from television which had taken to rewrapping old pictures as week-long events as a means of enticing viewers.

Although the Museum of Modern Arts in New York agreed to run a Garbo retrospective, that hardly produced the kind of box office juice that was required to kickstart a major revival. So Lesser bided his time, and in the end accepted a nine-day “filler engagement” in March 1971 for the 565-seat Murray Hill arthouse in New York. A “rousing” first week delivered $15,000 – $113,000 in today’s money – while the remaining two days hit a colossal $7,800.

Garbo was back – and in some style. Two months later the Garbo package returned to Murray Hill for a socko one-week $11,000 followed by a move-over to the 533-seat Paramount. And then it was game on.

One of the major elements of the Festival was its flexibility. It became an umbrella term. Exhibitors could decide whether to create a program out of single showings or double bills that could run for consecutive weeks or for an on-off event of single weeks interspersed over a longer period with other features.

In Chicago the double bill of Grand Hotel / Anna Christie romped home at the 505-seat Cinema with $8,500 in the first week and $7,500 – an amazingly low drop-off at the box office considering 40%-50% tumbles in the second week are the norm today – followed by Mata Hari / Ninotchka also on $7,500. In the same city Camille / Anna Karenina racked up $4,800 at the 598-seat Carnegie.

In Philadelphia a four-film package hoisted $19,000 running simultaneously at the 500-seat World and the 855-seat Bryn Mawr. The second week take dropped by just $1,500. Two more packages running each for a week brought in a total of $15,000. In Pittsburgh and Detroit the seasons also ran for three weeks.

But showings were not restricted to arthouses. In Cleveland the package played the 1,500-seat Beachcliff, in Dayton the 1,000-seat Cinema East and in Kansas City the 1,291-seat Midland.

Garbo’s name was kept alive all through the 1970s as revivals, either in one-week festivals, or shorter bookings, continued to bring in revenue across the USA and around the world, proving the continued box office potency of one of the industry’s greatest stars.

We’re still a few years away from the centenary of her Hollywood debut in MGM’s Torrent in 1926 so expect major reassessment then. Whether she breaks out of the arthouse confines and fuels new demand in the multiplexes might not be such a long shot. Release patterns for revivals have markedly changed, many now being promoted as “one-day-only” events (miss out at your own peril) rather than running over a week or longer. A major publicity campaign and the assistance of social media could change public perception of a star whose films embraced both the silent era and Hollywood’s Golden Age and who was never short of publicity.

In my opinion it’s always worth watching a Garbo film for one technical reason – the difference between male and female close-ups. Watch a Garbo picture and a close-up could last for minutes, the end of Queen Christina for example, as her eyes move through a variety of emotions. Male close-ups by comparison are over in a flash. With few exceptions the soul of a male actor is rarely revealed in close-up and even rarer is for expression to so dramatically change.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, Coming Back to a Theater Near You, A History of Hollywood Reissues 1914-2014 (McFarland, 2016) pp 33, 55, 56, 58, 75, 128, 130, 133, 212, 223-225, 232 “Test Garbo Retrospective at Royalty in London,” Variety, June 23, 1963, p11; “Garbo Pic Sets London Record,” Variety, August 15, 1963, p2; “Click of Metro’s Garbo Pix in London’s Empire Cues More Runs,” Variety, August 21, 1963, p19; “British Provinces May Get Metro Garbo Films,” Variety, August 28, 1963, p23; “Metro Classic (Garbo, Marx Bros, Tuners) Withdrawn from Market,” Variety, August 27, 1969, p3; “MGM Leases 65 Pictures for Re-Releasing,” Variety, August 10, 1970, p3; “Picture Grosses,” Variety 1971 – March 31, April 7, May 11, May 25, June 9, June 23, June 30, August 18, November 22, December 8.