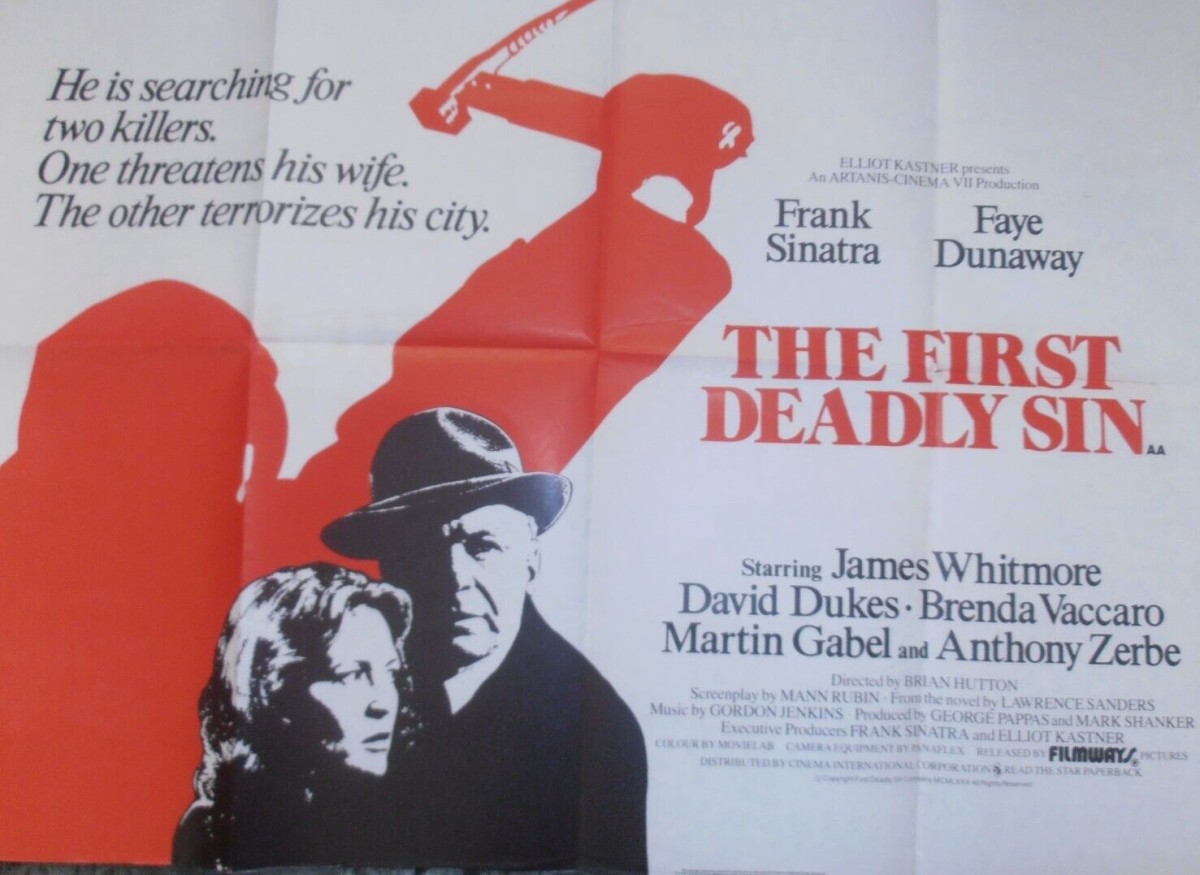

Highly under-rated. Mostly because star Frank Sinatra has the audacity at the age of 65 to play an older cop as an older guy, with none of the wisecracking or physical zap of his previous crime movies like Tony Rome (1967) and The Detective (1968). Deliberately downbeat and surprisingly compassionate with a gallery of unusual and realistic supporting characters.

Sure, we start off with a cliché, cop Delaney (Frank Sinatra) about to retire sniffs out a serial killer operating across New York. But that’s about as far as the cliches go. His boss (Anthony Zerbe) is highly territorial and doesn’t want Delaney doing work that might benefit any precinct other than his own. On top of that an operation on artist wife Barbara (Faye Dunaway) has gone seriously wrong and now she’s hooked up to all sorts of machines in hospital, Delaney sitting by her bedside reading from a book.

Unable to use the department’s facilities, Delaney is forced back on improvisation and enlists a museum curator Langley (Martin Gabel), an expert on weaponry, to find the specific type of tool the assailant is using to crack open heads. Langley is old, too, lacking in either wisecracks or physical zap, likely to doze off at inopportune moments.

Delaney isn’t above taking the law into his own hands, gaining admittance by devious means to the apartment of suspect Daniel (David Dukes) only to be told in no uncertain terms that not only has he no just cause to arrest Daniel, a high-flying executive with legal connections, but that any judge would immediately throw out the case thanks to the cop’s law-breaking.

So the movie settles into two parallel stories, both, if you like about observation. Delaney follows the suspect and he watches his wife die, in both instances unable to intervene, not able to prevent the murderer killing again unless he should happen to catch him in the act and as far as the hospital is concerned having to listen to a doctor (George Coe) tell him that doctors aren’t infallible and often get it wrong. Even his only ally, forensic expert Dr Ferguson (James Whitmore), is warning him off.

And where you might expect in another film a bit of romance between Delaney and witness Monica (Brenda Vaccaro) that doesn’t go anywhere either because he is a faithful husband and doesn’t need any distractions from a dying wife and she’s not the kind of woman that often turns up in crime pictures to form an adulterous relationship. If anything, she turns her attention to mothering Langley.

So this isn’t a fast action tough-talking crime picture of the kind audiences had been familiar with from the late 1960s/early 1970s, there’s no car chase to add entertainment heft. In fact, Delaney is an old-fashioned cop, I don’t think you even see him in a vehicle, he’s mostly pounding a beat of one kind or another.

And it’s oddly compassionate. There’s a lot of cross-cutting between the two narrative strands, and it soon becomes pretty clear that this is a different kind of killer, not one carefully planning his next murder, or taking sexual delight from the agony he inflicts, and he isn’t into abduction either, nobody corralled away in a basement or attic, night-time providing murky cover for his activities.

What we’re actually witnessing, it turns out, is a killer’s meltdown, as he hunkers naked in a bath or hides under bedclothes in a closet. And Delaney recognizes that insanity and that this is someone who needs treatment rather than being locked up in a prison. Daniel justifies his acts as a kind of purity. His victims are “all living inside me, I love them and they love me.”

The idea of sacrifice is embedded in the initial image of a neon-lit cross hanging above a street, the crucifix cross-referenced in several other scenes, and Xmas wet and miserable rather than Hollywoodized snow and ho-ho-ho.

So get your downbeat boots on and join the trudge and don’t start complaining this is lazy acting from Sinatra when actually he is delivering one of his finest performances. Nobody complained that Tom Hanks was lazy when he acted old in A Man Called Otto, where sorrow is similarly repressed, or that Hanks had a shade too much zest for a man his age. Faye Dunaway (Three Days of the Condor, 1975) has made an equally bold decision to play a woman who never gets out of bed and she makes no attempt, as an actress, to invoke your sympathy, there’s none of the cuteness you might expect from doomed romance. Critics, in general, have been put off by the fact that she plays a dying woman as if she is actually dying rather than about to spring into a song-and-dance.

You might be surprised to learn that director Brian G. Hutton (Where Eagles Dare, 1968) came out of a self-imposed seven-year retirement to make this picture, in some respects a companion piece to the equally down beat Night Watch (1973). And he makes a terrific virtue out of keeping characters realistic. Add Martin Gabel to the principals for playing old and slow when age dictates he’s old and slow. Screenplay by Mann Rubin (The Warning Shot, 1967) from the Lawrence Sanders bestseller.

Thoughtful, brooding picture, fitting finale to Sinatra’s career. This is the last hurrah without any forced Hollywoodized hurrah.

“It won’t be the same without you,” says the reception desk cop as Delaney hands in is papers. “It’s always the same,” retorts the world-weary cop.

But please go into it with your eyes open and not in expectation of the more typical 1970s crime movies.

Incidentally, I had thought this one of the lost movies, out of circulation due to legal shenanigans, so was pleasantly surprised when it popped up on YouTube.