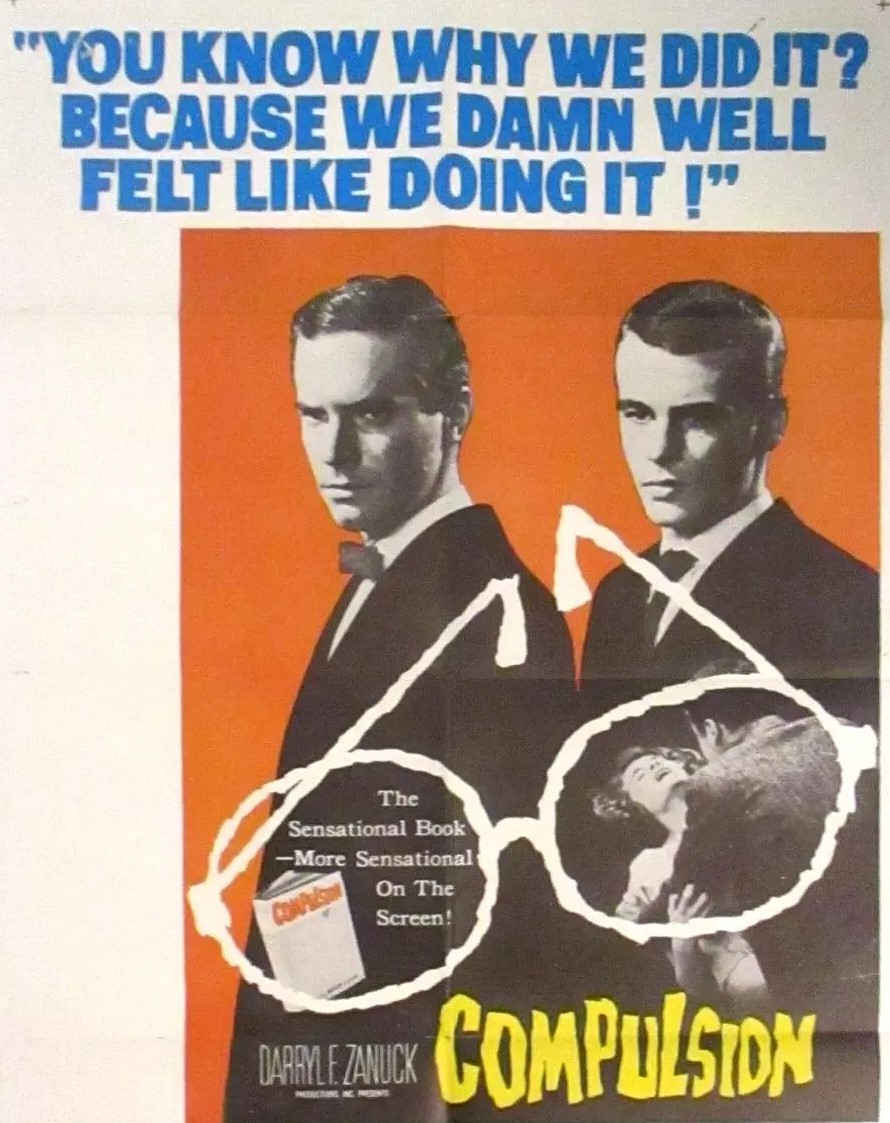

Controversy breeds controversy. Convicted killer Nathan Leopold was furious when author Meyer Levin reneged on his deal to write a book concentrating only on the murderer’s prison time, instead churning out a fictionalized account of the “crime of the century.” Levin’s novel, published in October 1956 by Simon & Schuster in the U.S., was snapped up by Darryl F. Zanuck for an upfront fee of $150,000 and the same again when the movie appeared.

A play, also ensnared in controversy, preceded the movie. Broadway producer Michael Myerberg was so dissatisfied by Levin’s script that he called in Robert Thom as co-writer. For his efforts Thom was due one-fifth of Levin’s share of the stage royalties. The play opened at the Ambassador in New York on 24 October 24, enjoying a healthy 18-week run.

There was contemporary feel to the cast given that, like now, Broadway was recruiting big names from Hollywood including Rex Harrison, Richard Burton, Walter Pidgeon, Anne Baxter, Joan Blondell, Paulette Goddard and for Compulsion rising star Dean Stockwell (Gun for a Coward, 1956). Actually, there was a heck of cast. As in the movie Stockwell played Judd. Roddy McDowell (Five Card Stud, 1968) played Arthur. But the big sensation was an “obscure actor” understudy Michael Constantine (Beau Geste, 1966), thrown into the limelight by illness, in the key role of the defense attorney. Also in small roles were Ina Balin (The Commancheros, 1961), Barbara Loden (Fade In, 1968), Suzanne Pleshette (Nevada Smith, 1966) and John Marley (The Godfather, 1972).

Levin complained he had been forced “under duress” to take on Thom as a co-writer and refused to pay him. The case went to court. Levin lost but he won a victory of a sort in writing Thom out of the play when it made its London West End debut. Meanwhile, Leopold was intent on his own revenge, on release from prison on parole in 1958 and having published his own autobiography, suing Levin and Zanuck, among others, for $1.5 million. He, too, was a loser in court.

In an early version of the nepo baby, Darryl F. Zanuck gave son Richard a leg-up by assigning him to be producer of the movie.

When director Richard Fleischer entered the equation Orson Welles was already cast as the defense attorney modelled after Clarence Darrow. The director might well have signed up on the strength of the script by Oscar-nominated Frank Murphy (Broken Lance, 1954). “It was the best I ever read,” he said. Among other things, Murphy had tightened up on the action of the play, removing scenes set in prison long after event, and taking a documentary-style approach to the film.

On hearing Welles was involved, “my tongue was hanging out,” admitted Fleischer. Given Welles’ murky finances, time was always going to be of the essence. Tax problems limited the amount of time – ten days exactly – he was available for shooting. And nobody was going to waste any of that valuable time on rehearsals. He arrived from Mexico on the day of the shooting and was booked onto a voyage to China the night filming finished.

Welles always supplied himself with a false nose, and that was the director’s first astonishing encounter with his star, on the first day of shooting. Welles explained his real nose was “just a button” and only once had appeared with it in a movie. He claimed Laurence Olivier was prone to the same insecurity. That wasn’t the actor’s only peccadillo.

He had trouble remembering lines. To cover this up he would claiming he was “reaching” for the words, actorspeak for showing thinking on camera. Fleischer discovered the way to challenge the actor over this was to tell him his reaching was so “realistic” it looked like he had forgotten his lines. In addition, Welles hated having anyone in his eye line, couldn’t cope with eye contact at all. So when it came for his part of a two-person scene he would play it to a blank wall, but with pauses, laughter, “exactly as though there were someone speaking to him.”

In the normal course of filming such a problem could be accommodated. It was a different story when it came to the movie climax, an 18-minute speech, the longest uninterrupted monologue in movie history. It was impossible to film it in one take. Apart from anything else, a movie camera only held ten minutes of film. So it needed broken down into smaller sections, some of which were quite long in themselves. As some of the speech was directed in general terms to the courtroom that didn’t demand eye contact so Welles was safe there.

But other sections had to be directed to the prosecutor (E.G. Marshall) and his team. To get round the problem of maintaining eye contact, Welles had a simple solution. All the other actors had to keep their eyes closed. And that’s what they did. Fleischer recalled as “a ludicrous but memorable sight” seeing all the actors “line up, listening intently, with their eyes closed.”

Only four days were left for the speech. So the director pointed his three cameras in one direction and shot every section of the speech that applied to, then moved the cameras around until he had completed a 360-degree rotation. However, the last section was filmed in one complete, technically complicated, three-minute section. It was rehearsed to fulfil the technical criteria and then Welles was left alone on the set for a couple of hours to do his own rehearsal. He didn’t want Fleischer to see any of his performance beforehand, just come in and film it. In other words, trust the actor. A dangerous proposition given this was the second last day Welles was available. However, Welles delivered a virtuoso performance captured by intricate camerawork.

To save money, the studio had revamped a set from another picture, dressed up with “a little paint, some different trim…a set for almost no cost.” Fleischer had redressed an older that set lacked one wall. Welles, clearly unaware of budgetary problems, wanted to make his exit from the scene through the side that had no wall. Told that was impossible, Welles noted that, if director, he would have stood up to the studio, forced them to build a wall so he could exit in the manner that seemed most appropriate. “That’s why I’m directing this picture and not you,” was the director’s prompt reply.

Needless to say, Welles was not always on his best behaviour. Sometimes, he was playing to the gallery, especially if the producer hove into view, or if he was feeling narked that a director with conspicuously lesser directorial skills was in charge. Among those to receive both barrels were a hapless stills photographer and a publicity man guilty of an imaginary slight. Both these incidents could be brushed off, the collateral of tension on any movie. It was a different story when the director was in the legendary actor’s sights, as occurred when Welles had the opportunity to view dailies. He took the film apart, “a total disaster from beginning to end.” Explanation for the unexpected explosion came from the fact that his salary had been “garnished” by a tax official, meaning he wouldn’t be paid.

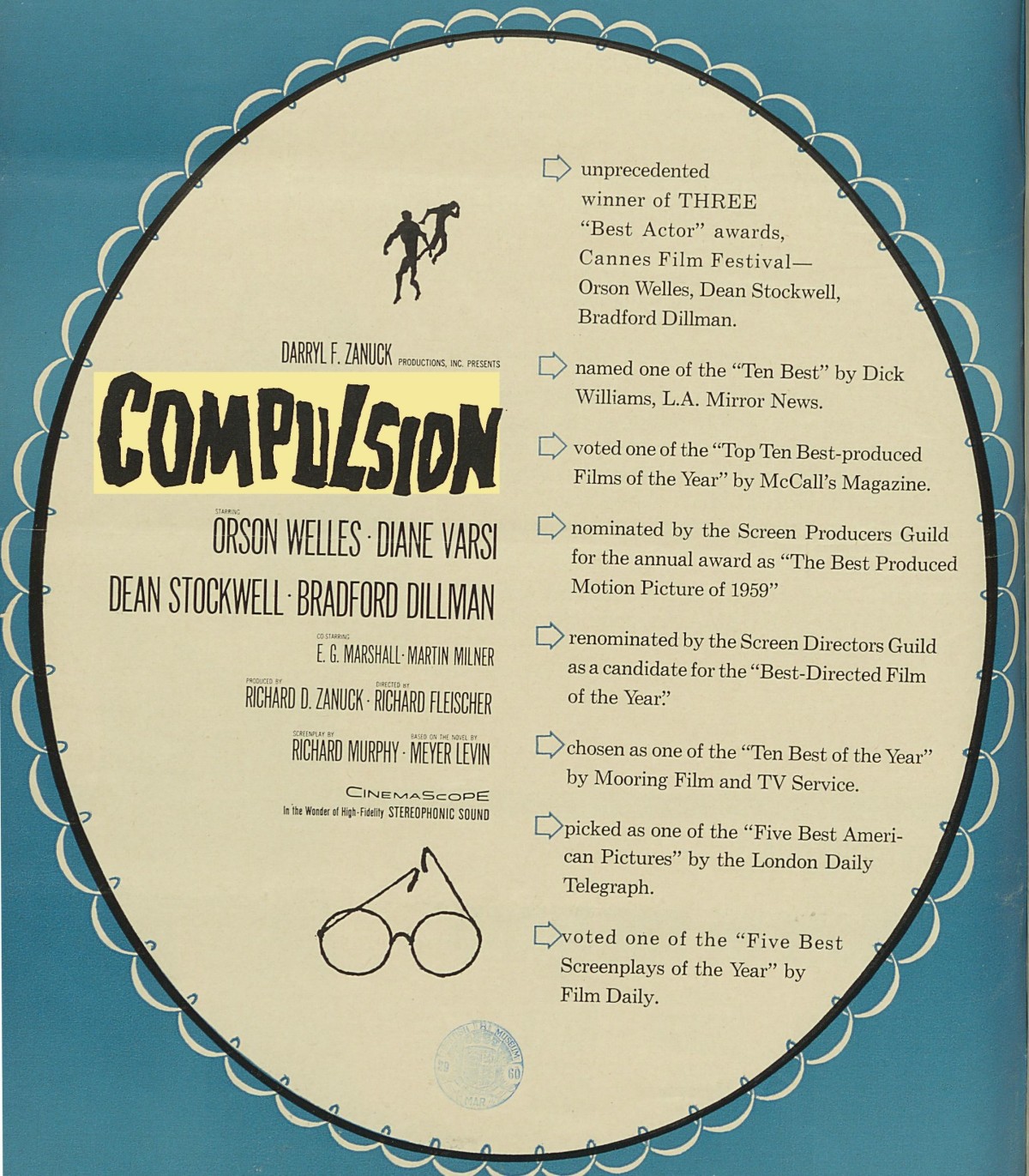

At Cannes the three stars shared Best Actor honors. Fleischer was nominated for a Bafta and a DGA. Despite fears that to avoid stirring up old controversy Chicago would be denied a release, that city proved one of the earliest to show the movie. It did well in the big cities, less well elsewhere. Rentals were a disappointing $1.8 million, ranking it 48th for the year. In London, exhibitors exploited the old gimmick of denying patrons entrance once Orson Welles lumbered to his feet for his big speech.

Despite success in the big-budget adventure field with movies like 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (1954) and The Vikings (1958), Fleischer hankered after independence. He set up his own shingle Nautilus but complained that with so many “properties” tied up by the studios, and likewise marquee names, he was reduced to “combing library shelves and finding properties major studios had missed.” He had three projects on his planned indie slate – Willing Is My Lover, an original screenplay by Frank Murphy, an adaptation of Tolstoy’s Resurrection and Trouble in July by Erskine Caldwell. But none ever saw the light of day.

SOURCES: Richard Fleischer, Just Tell Me When To Cry, Carroll & Graf, 1993, p161-175; “Writers Harvest,” Variety, December 5, 1956; “Compulsion Producer,” Variety, September 25, 1957, p1; “Legit Increasingly Recruits Players from Film,” Variety, October 9, 1957, p63; “Shows on Broadway,” Variety, October 30, 1957, p82; “Levin Withholds Thom Royalties for Compulsion,” Variety, December 11, 1957, -p73; “Meyer Must Pay,” Variety, March 12, 1958, p73; “Meyer Levin to London,” Variety, December 28, 1958, p49; “Old Gimmick, New Pic,” Variety, May 13, 1959, p12; “Properties, Stars Monopolized,” Variety, July 22, 1959, p10; “Now-Free Slayer Sues on Privacy,” Variety, October 7, 1959, p21.