Given the surprising success of the reissue of Jaws this weekend – it came in second at the U.S. ticket wickets ahead of such new films as The Roses and Caught Stealing – I thought you might like a second look (or a first one) at exactly how Universal created box office history. And it was not the way you would expect. It did not follow the template set out by previous juggernauts.

Naturally, the hoopla surrounding the 50th anniversary of Jaws concentrates on the budget overruns, director Steven Spielberg’s problems and the mechanical shark, and no one gives a hoot about the most important aspect of the picture – the box office. Sure, it’s always mentioned in passing, because otherwise the movie would have had little impact on pop culture, the driving force of the water cooler effect when so many people see the same movie at the same time it drives word-of-mouth into the stellar regions.

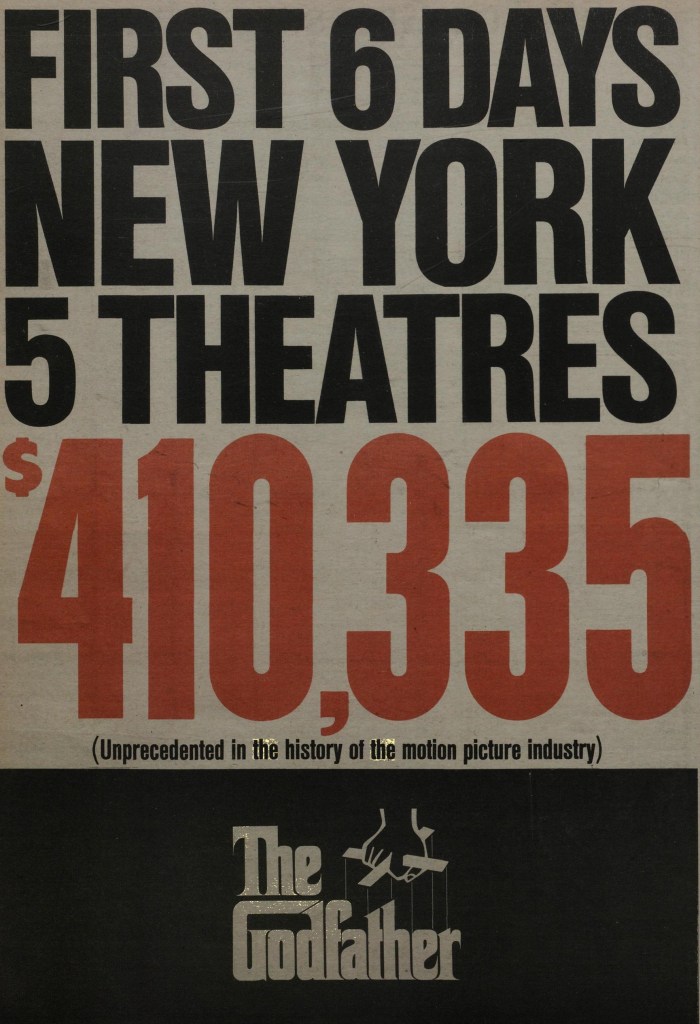

What is little known is how Jaws changed the release system forever. Even The Godfather (1972), its predecessor in topping the box office firmament, while spreading the goodies amongst nabes and the showcase houses did not ignore first run. In fact, for The Godfather Paramount used five New York first run houses – the 1025-seat Orpheum, 1175-seat State I, 1174-seat State II, 599-seat Cine and 588-seat Tower East – to create a pre-emptive strike. This quintet screened the movie exclusively for the first week, permitting the studio to trumpet the record-breaking results.

The other 350-odd cinemas had to wait a further week to get their hands on the gangster saga.

For Jaws, on the other hand, Universal completely froze out New York first run. Not a single first run house was given access to the picture on its initial release on this weekend 50 years ago.

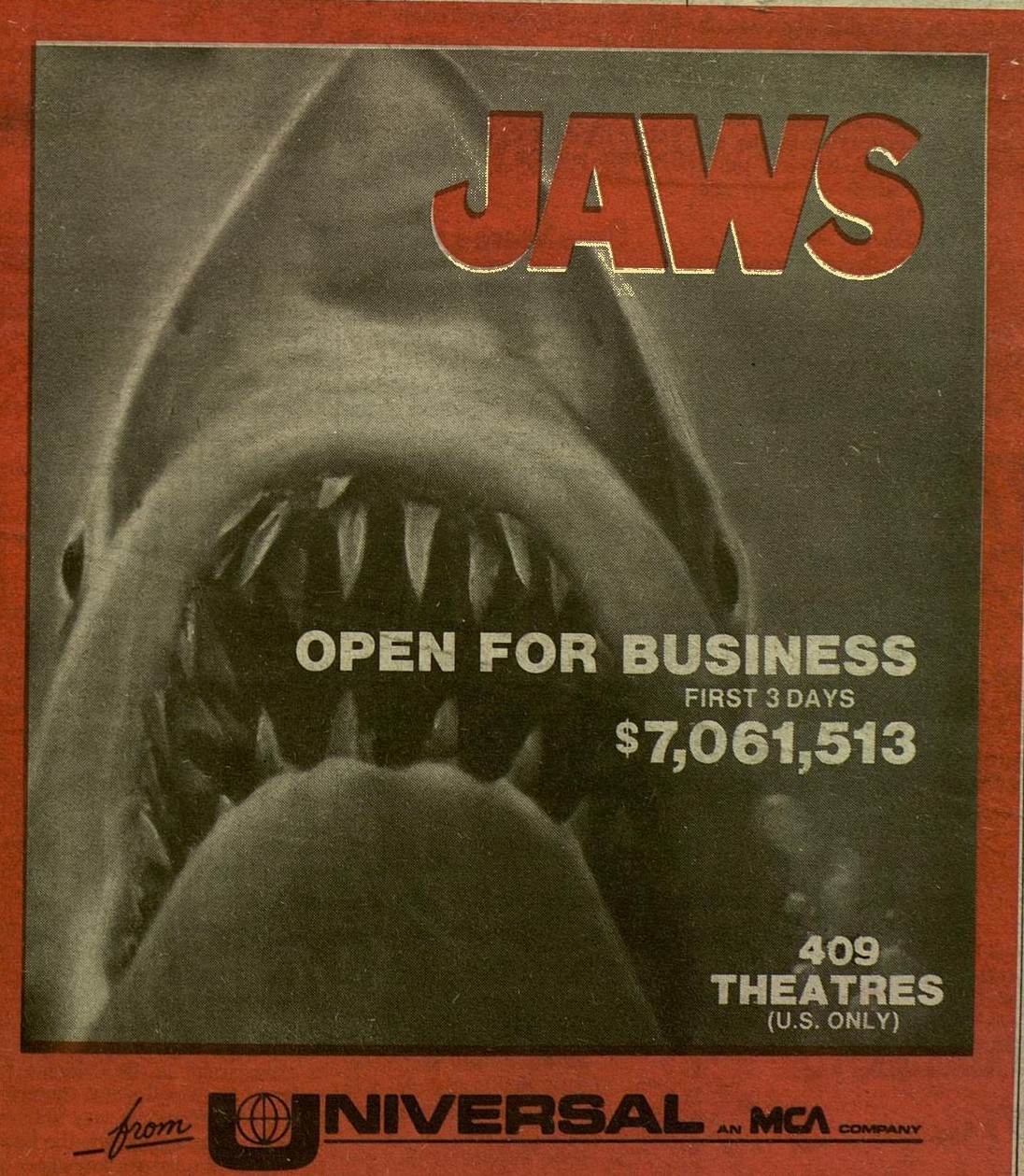

Instead, in New York, Universal went down the showcase route and clocked up just over $1 million in the first three days at 46 cinemas. Prior to Jaws, the only pictures that would open first in showcase in New York and ignore that city’s vibrant first run were those that first run would most likely have declined to show.

With Jaws, across the country Universal was as ruthless in squeezing out first run if it could make a better deal in the nabes and drive-ins. So while Jaws set house records at all the first run houses that were deemed up to standard, it also creamed the nabes and drive ins. Significantly, not all the first run houses chosen would have been the first choice of most studios for a major picture. You wouldn’t have expected this behemoth to end up at the 925-seat Gopher in Minneapolis where it took in $47,000. Similarly, the 900-seat Charles in Boston ($55,000 take) would not have been your first choice (and it’s worth noting that it was only in this city that the movie did not top the week, beaten into second place by Woody Allen’s Love and Death at the 525-seat Cheri Three).

By and large, Universal picked off those first run cinemas that were so delighted to be asked they agreed to the tough terms – a 90/10 split in the studio’s favor and a 12-week run.

Other first run destinations included the 800-seat Cooper in Denver ($53,000 for openers), the 1670-seat Coliseum in San Francisco ($68,000), the 900-seat Southgate I and 550-seat Town Center II in Portland ($55,000 total), the 1836-seat Gateway in Pittsburgh ($70,000) and the 1287-seat Midland in Kansas City ($55,000). In these cities, the premiere outing was restricted to first run.

But while in Chicago the 1126-seat United Artists hauled in $116,000 in the opener, Universal played it canny by screening it simultaneously at four other nabes which brought in another $260,000. It was the same in Cleveland where the 455-seat Severance II was the only first run house among the five cinemas that hoovered up a total of $84,000. The first run 500-seat Goldman in Philadelphia was the only first run location among the total of 15 cinemas that knocked up $312,000.

Elsewhere, echoing the New York approach, first run cinemas were frozen out in Detroit, Buffalo and San Francisco. In Detroit seven nabes gobbled up $350,000, in Buffalo a deuce of nabes snatched $50,000, in San Francisco a trio set about $75,000.

We’ve all seen movies driven to opening weekend box office heights on the back of heavy advertising or hyperbole only to take a dive in the second week. And the fact that Universal was not making an “event” out of its movie by restricting it to first run meant that the sophomore weekend could easily have brought disaster.

Instead, receipts at virtually all the cinemas either beat the first week or fell only fractionally below. The opening weekend appeared to set the tone, every successive day better than the previous one.

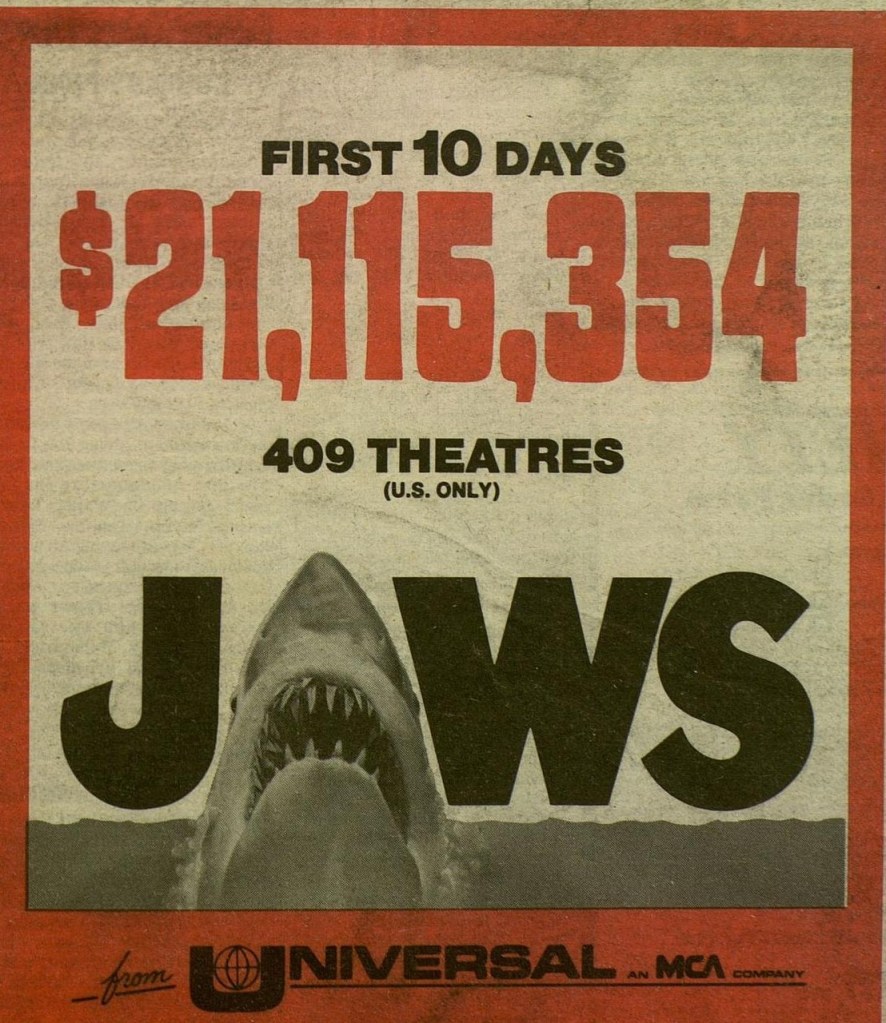

Universal immediately set its sights on taking down The Godfather and began posting weekly advertisements in the trade papers hyping its performance at the box office. But in nudging first run out of the equation, it triggered the slow decline of first run houses.

Tomorrow, you can catch on my article that sunk many of the other myths surrounding Jaws, “Behind the Scenes: Exploding The Myth of Jaws.”

SOURCE: Variety.

I thought you might like this:

“A 4 May 1973 DV news item announced that producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown and Universal Studios had acquired Peter Benchley’s first novel, Jaws, for $250,000 and 10 percent of the profits. A 21 Jun 1973 DV item revealed that Zanuck and Brown had signed Steven Spielberg, who had directed an earlier film for the producers, the 1974 Universal release, The Sugarland Express (see entry). According to a modern biography on Spielberg, the director, who had worked several years in Universal’s television division and made only one previous feature film, was not the first choice for directing Jaws. John Sturges and Dick Richards were initially considered. The Spielberg biography states that a bidding war for the novel transpired between Universal and Columbia, then Universal and Warner Bros. The novel by Benchley, who makes a cameo appearance in the film as a reporter interviewing “Mayor Vaughn,” was loosely based on a 1964 New York Daily article about Long Island fisherman Frank Mundus, who had harpooned a shark weighing 4,500 pounds. Mundus is mentioned in Spielberg’s biography and elsewhere as the prototype for “Quint.” A 14 Sep 2008 obituary for Mundus noted that Benchley, who admitted to having spent several weeks fishing with Mundus, nevertheless denied that Mundus was the inspiration for Quint. Mundus spent years using methods to kill whales and sharks that were later outlawed, but he later became a shark conservation activist, lobbying for “catch and release.” The Great White shark that had established Mundus’s career was eventually declared an endangered species. In addition to Mundus, Benchley was also influenced by the 1971 documentary, Blue Water, White Death, a National General release photographed by Ron Tyler.

The Spielberg biography states that when Richard Dreyfuss originally turned down the role of “Hooper,” Jon Voight, Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges and Joel Grey were all considered. Charlton Heston expressed interest in playing “Brody,” but actors Joe Bologna and Robert Duvall were approached. Duvall, reportedly, preferred the role of Quint. The film’s producers initially expressed concern at casting Roy Scheider as the hesitant and anxious Brody, as the actor was typically cast in “tough guy” roles. Lee Marvin turned down the role of Quint and Sterling Hayden was prevented from accepting the role due to income tax difficulties.

The Spielberg biography states that Howard Sackler refused screen credit for working on the script and contributing a scene, not found in the novel, in which where Quint relates the story of the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis. The biography adds that World War II history buff John Milius and Robert Shaw improvised on Sackler’s scene. Carl Gottlieb, an acquaintance of Spielberg’s, was brought in to polish Benchley’s script and utilized cast input on their characters. Modern sources state that Scheider improvised the film’s most memorable line: “You’re going to need a bigger boat.” Side plots from the novel that were cut from the script were the romance between “Ellen Brody” and Hooper, the dynamics between the island natives and summer tourists and the mayor’s shady political connections.

Photography for Jaws took place off of Martha’s Vineyard, MA, and was the first feature film set at sea that did not use process photography or film in a tank. The Spielberg biography notes that initially live sharks were to be used. Ron Tyler and his wife Valerie agreed to shoot live shark footage off the coast of Australia, but when a double for Richard Dreyfuss’s character, “Hooper,” was nearly killed filming the cage sequence, the use of sharks was halted. A brief amount of the Tylers’ footage made it to the released film in the cage sequence without the double. An unidentified 11 Aug 1974 article on the film’s production, describes three polyurethane mechanized shark models designed for the film. An article in the 2 Sep 1974 issue of Time states that the three twenty-five foot long models, all nicknamed “Bruce,” were created by former Walt Disney special effects chief, Robert Mattey and Jaws art director Joe Alves. One of the models was to be filmed from the right side, the other from the left and the third for angled shots. The models were operated from an underwater platform powered and manipulated by a hydraulic crane “arm.” The article and the Spielberg biography note that the sharks malfunctioned on several occasions and that the models corroded easily and had to have fresh skin applied weekly due to sun bleaching. The mechanized shark breakdowns and bad weather heavily affected the film’s shooting schedule and ultimate cost, and prompted Spielberg to consider withdrawing in mid-production. According to the 2 Jun 1975 DV, the picture was initially slated for a three to four million dollar budget, but ended up costing eight million. Various modern sources extend the cost to ten million.

The Spielberg biography notes that many associated with the production of Jaws agree that the completed film was greatly enhanced by Verna Fields’s editing and the ominous score by John Williams. The musical riff that played whenever the shark was present, even if not visible, has since become one of the most iconic pieces of music in cinema history.

Reviews following the film’s opening in May 1975 were mostly positive, with DV calling it “an artistic and commercial smash…a film of consummate suspense, tension and terror.” HR described Jaws “as gripping and terrifying an adventure story as has ever been put on the screen,” while the NYT labeled it “foolishly entertaining.” A 7 Jul 1975 HR article noted the dissatisfaction of several viewers that the film had been awarded a PG rating, rather than R, for excessive violence. In the article, then MPAA president Jack Valenti explained the decision was due to the violence being done by nature rather than by man. Producer David Brown is quoted in the article as denying that any pressure was put on the MPAA board from Universal officials to ensure Jaws was rated PG. According to a 8 Jul 1975 NYT article, Jaws had receipts of $25.7 million in its first thirteen days of release nationwide. In the article, Universal stated that the revenue was the highest for a movie in so short a time and broke the previous box-office record set by the 1972 Paramount release, The Godfather (see entry). The article compared the commercial success of Jaws with that of the 1973 releases The Exorcist and The Sting (see entries). Jaws’s success was, according to the article, based on being “pre-sold through the popularity of the novel,” and the combination of suspense and disaster-film qualities that appealed to audiences early in the decade. Articles in both DV and HR on 10 Sep 1975 announced that Jaws had become the most successful motion picture in the U. S. and Canada in the history of the industry, taking over from The Godfather. By May 1977, Jaws hit the $200,000,000 mark based on worldwide receipts. Many film historians consider that Jaws, in addition to the Twentieth Century-Fox May, 1977 release, Star Wars, contributed to an industry precedent for releasing action-adventure films with high box-office potential, at the start of summer holidays.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I queued round the block for this one and when I came out I rejoined the queue and saw it again. Thanks for your wonderful contribution.

LikeLike