Style is just about the only weapon in the directorial armory to mitigate against lack of budget. Or you can rely on a narrative twist. But in sci fi you’re inevitably going to come a cropper in this era and on a low budget when it comes to the special effects.

As director Alan Bridges would later prove in bigger budgeted efforts like The Hireling (1973) and Out of Season (1975) he was a genius at building atmosphere. Here, he also makes very effective use on the long shot. Not in the usual dramatic fashion of depicting a vista, but in building tension.

There’s a fabulous sequence which is superbly done given the budget. There’s a car crash. We see a window exploding. Next shot shows a man dead and bloodied sprawling over the hood. The car has crashed about a hundred yards away from a hospital where the main character Mike (Edward Judd) is standing outside. Instead of cutting to his face to register the shock, the camera stays where it is just to the side of the car so we can see the corpse and in the background watch Mike’s reaction. But he doesn’t race towards the camera. He moves in puzzled fashion, glancing around, even taking a step backward.

So where another director would in effect have speeded things up – crash, onlooker reaction – Bridges slows it all down. That’s the real purpose of the long shot. To waste vital seconds. To slow everything down.

There’s a reason why Mike is so slow on the uptake. Because there’s nothing for the car to crash into. There’s not a tree or a wall to get in the way of the moving car. This is the moment Mike works out there’s a force field surrounding the hospital, generated by the strange patient inside, who needs protection from his pursuers.

Sure Bridges uses long shot for budgetary reasons, to have all his characters in the same space without having to spend money on close-ups, but most of the time it’s for atmosphere and effect. There’s another great long shot of seated hospital patient Blackburn (Anthony Sharp) viewed from the other end of a long corridor. He’s in shock not just because he’s knocked down a pedestrian in unseasonal fog during the night but because he was with his mistress at the time and there is bound to be consequence.

And perhaps because his lover urged him not to stop, so that will change the dynamics of their relationship. And perhaps because the person he knocked done is so strange, walking around in some kind of plastic uniform in the middle of the road as if he didn’t know where he was going.

We’ve had decades now for movie makers to find ways of indicating the imminent arrival of aliens, and usually they’re able to call on bigger budgets and scenes of television reports to do so, witness Independence Day (1996) or Arrival (2106) and even have the luxury of delaying such action until they can introduce some of the characters.

Here, Bridges manages that in minimalist fashion. And without delay. Soldiers manning a radar station notice the radar misses a beat, on the road Blackburn’s vehicle inexplicably and momentarily stalls while in motion, in the hospital an iron lung inexplicably stops pumping oxygen into the inert patient for a moment. We don’t realize it until some time later but that’s the sign of arrival.

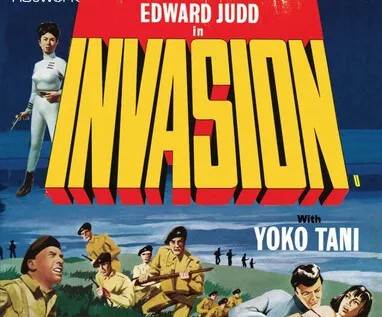

In the hospital the foreigner (Eric Young) is found to have a metal plate in his head. He appears surprised that women do as they’re told. The building begins to become unbearably hot. When the stranger awakens, we discover he is, in fact, an alien, from a distant planet, strayed from his course. He was escorting two female prisoners.

And sure enough every now and then we get a glimpse of the female pair outside in close-fitting uniforms. Phone lines are down. The rising heat threatens the chances of survival of the hospital’s 300 patients. Hospital chief Carter (Lyndon Brook), going for help, is the one who dies in the car crash.

Very snippy doctor Claire (Valerie Gearon), severe haircut indicating a no-nonsense personality, interrogates the alien and gets far more out of him than Mike or Carter. Meanwhile, Mike works out that the force field is less effective with water, so he escapes via the sewer, finds the alien’s power pack and returns so the alien can leave and find his spaceship, though by now they know he is an escaped convict not an officer of alien law.

And this is the kind of picture when a fellow undertaking superhuman activity, like crawling along a sewer and hauling himself out the other end, doesn’t do this in the blithe fashion of a hero. He is exhausted, staggering, completely wrung out.

Oddly enough, the special effects, given the budget, stand up. The alien takes off in his rocket but another alien craft shoots him down.

Despite the storyline with the feminist angle and the twist of alien being bad guy and not good guy, there’s not enough here sci fi-wise for it even to get an honorable mention in the list of great low-budget sci fi movies.

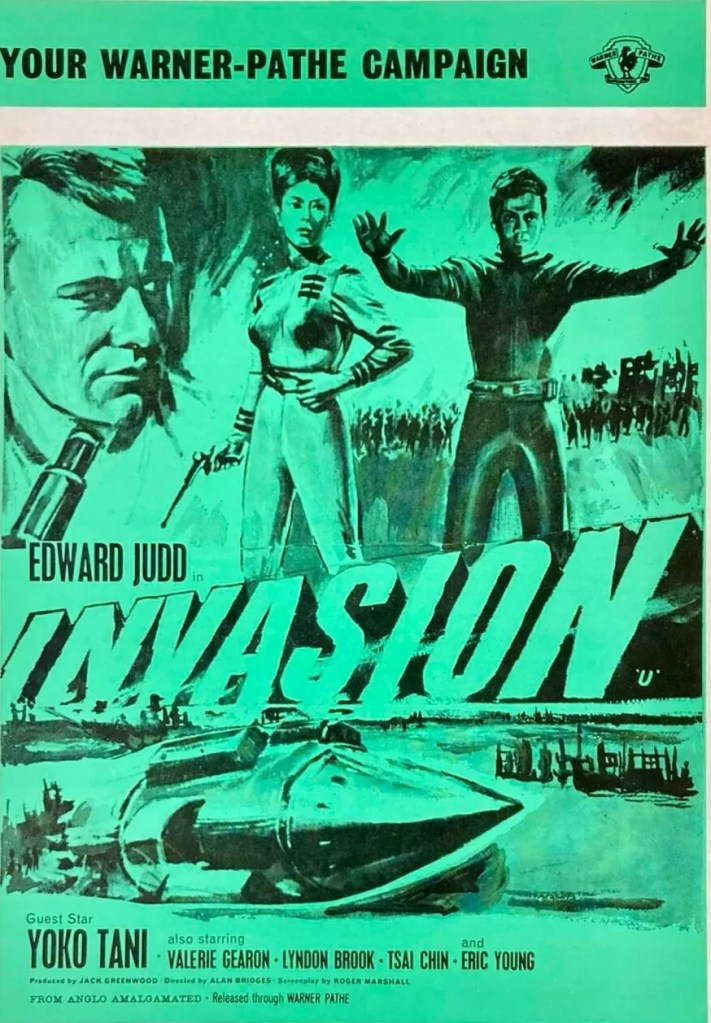

The fact that it deserves any mention at all – and it fully deserves one – is down to the direction. There’s a throbbing score by Bernard Ebbinghouse (Prudence and the Pill, 1968) that helps maintain tension. And the hospital staff, mostly called upon to sweat and be at the end of their tether, come over as very human, Edward Judd (First Men in the Moon, 1964) and Valerie Gearon (Nine Hours to Rama, 1963), especially. Roger Marshall (Theatre of Death, 1967) wrote the screenplay.

But Alan Bridges is the star.

Minor gem.

I remember Edward costarred with Rock Hudson n Gina Lollobrigida in the fairly successful comedy Strange Bedfellows.

LikeLike