Turns the POW sub-genre on its head. Nobody’s interested in escaping or, in the vein of Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), committing an audacious act of sabotage. It’s hard enough just surviving with any high-falautin’ notions of honor or courage getting in the way.

Imagine if the James Garner character in The Great Escape (1963) was wheeling-and-dealing to fill his own pockets or ease his confinement in the way of Morgan Freeman in The Shawshank Redemption (1994).

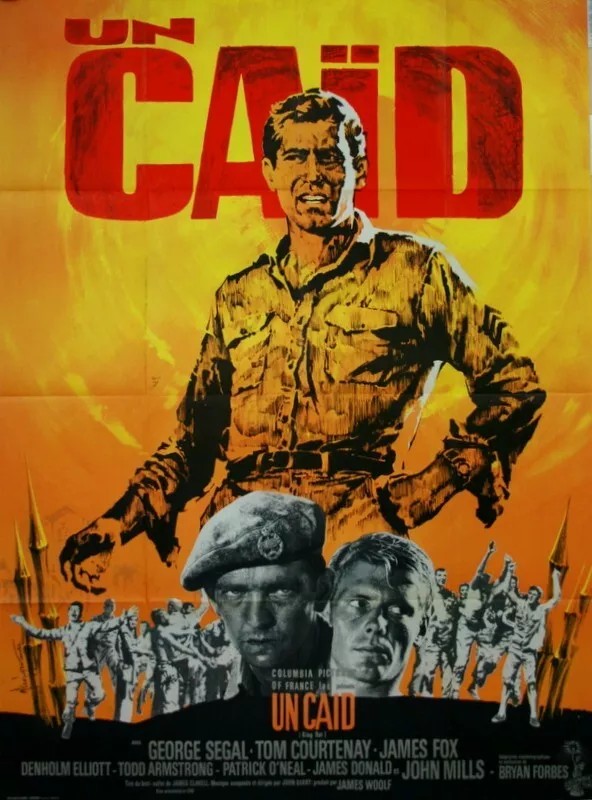

That’s what we’ve got here. American prisoner Corporal King (George Segal) hasn’t got the general good in mind. He’s only interested in number one. The British idea of “fair play” doesn’t register. But, of course, there being Brits involved, there’s the whole class thing. Officers are generally upper-class and speak with pronounced drawls and affect that this whole prisoner-of-war lark is merely tiresome. Throw into the equation as well as kind of Lord of the Flies scenario where ideas of civilization are rudely interrupted by desperate need to claw to the top.

Three narratives intertwine. King’s black market activities attract the ire of the British security chief Lt Grey (Tom Courtenay), who, despite his position is clearly working class. King befriends airman Lt Marlowe (James Fox) who, though occasionally sticking to some honor code, gradually drifts away from any notions of upright behavior into the seductive immorality implicit in dealings with the American. And while investigating the theft of rations, Grey comes up against the brick wall of camp commander Col Smedley-Taylor, who while distinctly upper-class, nonetheless is a realist and keeps the situation on an even keel.

In the background, of course, is deprivation. Men commit suicide if caught stealing – and in quite awful fashion, diving headfirst into the dung-hole and suffocating.

In due course, King, as the title of the picture suggests, hits upon the notion of breeding rats and selling the food to the other prisoners under the guise of calling it “mouse-deer,” a genuine species in the area.

Complicity in corruption lingers, Grey assuming that Smedley-Taylor is glossing over punishment for the thefts, while all the prisoners begin to view King in a better light once he becomes the source of much-needed nourishment.

Mostly, though it’s about the characters and therefore about the acting. Tom Courtenay (Otley, 1969) is the least interesting, we’ve seen this snarky grumpy screen persona too many times before. George Segal (The Quiller Memorandum, 1966) is the revelation. He’s so charming it’s sometimes difficult to realize that he’s the villain of the piece, the unscrupulous soldier taking advantage of circumstance. He might be like your local drug-dealer, the criminal aspect of his activity overlooked because people want so badly what’s he’s selling.

The impact of James Fox (Thoroughly Modern Millie, 1967) is largely down to the fact that he plays against officer type, that one of the supposed good guys goes along with King and junks his stiff-upper-lip when easier pickings are on offer. But John Mills (The Family Way, 1966) is the other standout, determined not to make waves that will only upset a delicate order. You’ll catch Patrick O’Neal (Stiletto, 1969) and Denholm Elliott (Maroc 7, 1967) in small parts and a whole host of British supporting actors.

Writer-director Bryan Forbes (Deadfall, 1968), adapting the James Clavell bestseller, keeps the package taut, allowing the actors to do their stuff.

Also found this:

“According to a 29 Jul 1962 NYT article, screenwriter-producer-director James Clavell decided to write his first novel, King Rat, after he began telling anecdotes to friends about his experiences at Changi Prison in Singapore, where he spent three years as a prisoner during World War II. Before the book was completed, the 22 Jun 1961 DV announced that Clavell had established Cee Productions, which would retain motion picture rights for an eventual feature film. Little, Brown and Company published King Rat in the summer of 1962, around which time Columbia Pictures purchased the property from Clavell for $157,500. A 1 Aug 1962 DV report indicated that the deal also included ten percent of net profits. According to the 22 May 1963 Var, Clavell decided against adapting his own work for the screen, but embarked on a trip to Southeast Asia to “reacquaint himself” with the region. At this time, the budget was set at $4 million.

An LAT article published that same day indicated that producer Carl Foreman hoped to shoot the picture near Singapore with a cast of esteemed English actors, including Peter O’Toole, Trevor Howard, John Mills, and Albert Finney. By the end of the year, however, Foreman decided to leave the project. The 8 Nov 1963 LAT quoted him as saying, “I feel now I have nothing more to say about war,” after four consecutive pictures on the subject, three of which dealt specifically with WWII. James Woolf signed on as his replacement, while British actor-turned-filmmaker Bryan Forbes worked on the screenplay and prepared to direct his first Hollywood feature.

Throughout the early stages of development, multiple sources referenced plans to shoot the picture in Asia or England, but Forbes told the 10 Jul 1965 NYT that he and his team were deterred by the heat and tropical conditions of the Singapore locations, and opted instead to recreate the setting in Southern California. The article noted that this choice reflected a recent change in trend that saw more filmmakers choosing to shoot domestically, partly due to rising production costs overseas. However, the decision posed other problems, since the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) began aggressively enforcing rules preventing filmmakers from using foreign actors for roles that could otherwise be played by Americans. The 7 Feb 1965 NYT claimed that Columbia attempted to hire expatriates for thirty-eight such roles, but only eight were approved.

According to a 27 Feb 1964 LAT item, Frank Sinatra and Steve McQueen were both approached to play U.S. “Corporal King” before Forbes selected the relatively unknown George Segal. Items in the 27 Jan 1964, 17 Apr 1964, and 25 Aug 1964 LAT and 10 Sep 1964 DV reported that Vince Edwards, Michael Callan, Chris Warfield, and Robert Wagner were also considered for roles. LAT confirmed eight of the principal actors on 17 Sep 1964, while announcements in the 5 Oct 1964 and 9 Dec 1964 DV named Mickey Simpson, William Beckley, James Forrest, and Brian Goffiken among the supporting cast, although they may have been uncredited.

A 9 Oct 1964 DV production chart indicated that principal photography began 21 Sep 1964. Nearly all of filming took place on a twelve-acre recreation of Changi Prison constructed at the Glenmore Ranch in Thousand Oaks, CA, which a 30 Sep 1964 DV article claimed required the work of two hundred laborers. Roughly half were hired on “permit,” as the trade unions could not meet the demand alone. Approximately 300 feet long, the set contained a large vegetable garden and cabbage patch, three miles of roads, palm trees, and fifty-two bamboo huts, which were fully decorated for interior filming. Only two or three scenes were expected to be shot at the Columbia studios in Hollywood. While the story listed expenses of $400,000 (plus the cost of foliage), the 27 Aug 1964 DV estimated a much higher price of $750,000. According to the 21 Oct 1964 LAT, photography was scheduled to conclude 20 Dec 1964.

Despite Forbes’s plans to score, edit, and dub the film in London, England, a 9 Apr 1965 DV brief revealed that composer John Barry was required to work in Hollywood at the insistence of the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) Local 47 union.

A preview screening took place 26 Oct 1965 at the Directors Guild of America theater in Los Angeles, as stated in an LAT item two days later. Afterward, Mike Nichols hosted a party at Whisky a Go-Go in honor of Segal, who was currently filming the director’s first motion picture, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966, see entry). According to the 19 Oct 1965 DV, King Rat was set to open 27 Oct 1965 for a “world premiere” engagement at the Victoria, Beekman, and Murray Hill theaters in New York City. The Los Angeles release began the following week, on 5 Nov 1965, at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

King Rat received Academy Award nominations for Art Direction (Black-and-White) and Cinematography (Black-and-White).”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant article. Thanks very much.

LikeLike

Thanks very much. Brilliant stuff.

LikeLike