Film noir gem with terrific cast filmed in black-and-white and often at night that crams into a taut storyline different slants of the themes of the con-going-straight, the vendetta and the double-cross. While Hollywood at this point had imported platoons of foreign beauties in the Sophia Loren-Elke Sommer vein, there had been less interest in the male of the species with the exception of a small British contingent and possibly Omar Sharif, on whom the jury was still out.

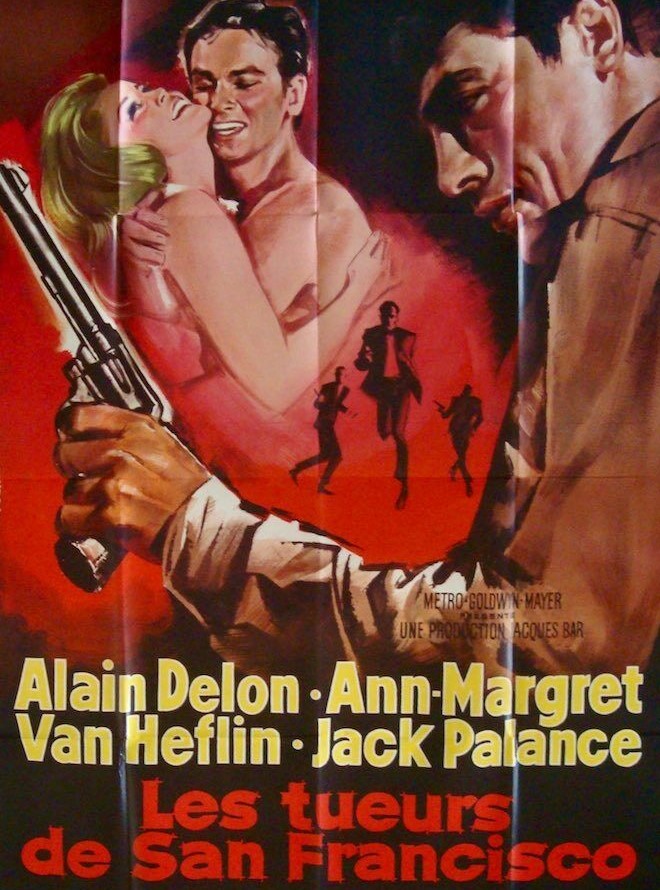

MGM was gambling on Frenchman Alain Delon (Farewell Friend / Adieu L’Ami, 1968) to alter industry perspective at the same time as pushing new contract star Ann-Margret (The Swinger, 1966) along more dramatic lines away from the glossy puffery that had made her name and which relied more upon her physical assets than acting potential. Had she continued in this vein, her career would certainly have taken a different turn.

Eddie Pedak (Alain Delon), former minor hood turned San Francisco truck driver, is happily married to Kristine (Ann-Margret) with a young daughter they both adore. But tough cop Mike Vido (Van Heflin), with a reputation for brutality, is determined to pin a murder on him in revenge for purportedly being shot by him early in Eddie’s previous career. Eddie manages for a time to resist the overtures of brother Walter (Jack Palance) to participate in a million-dollar diamond heist. But when he loses his job, that changes.

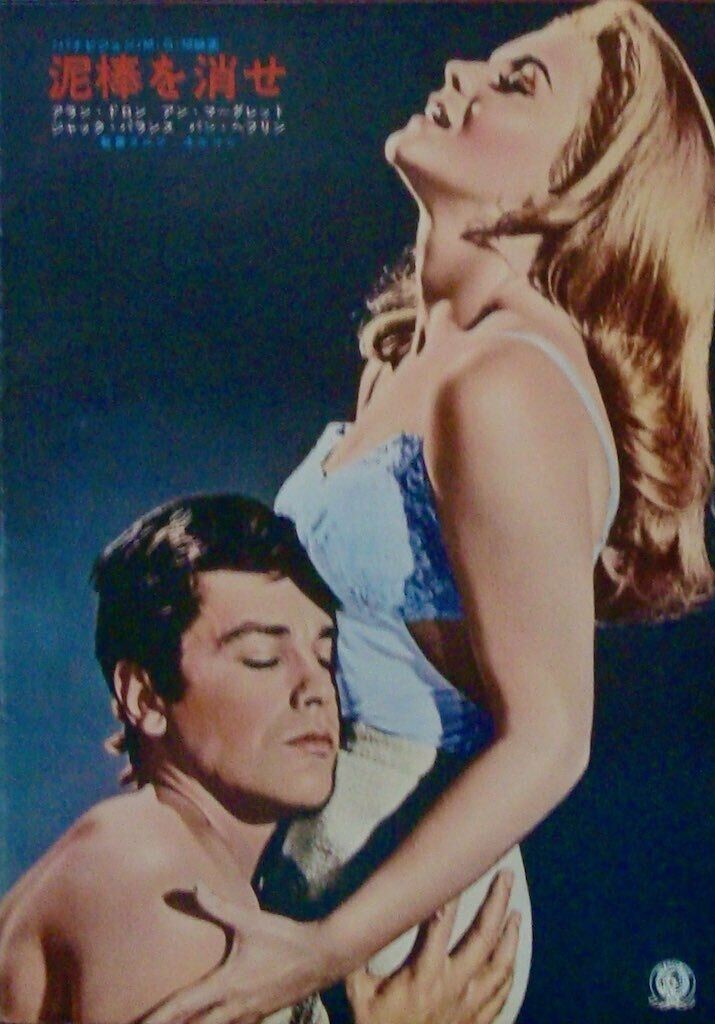

While the robbery naturally takes center stage, that’s not actually the dramatic highlight. Instead, it is the Eddie-Kristine relationship. Instead of Eddie being the usual down-on-his-luck ex-con, he has clearly turned his life around, so much so he can afford a $500 down payment on a small boat. A loving father, he accepts without rancor when his daughter interrupts a night-time lovemaking session. And he’s stylish, too, wearing an iconic sheepskin jacket and driving a snazzy 1931 Ford Model A roadster. Kristine just wants a normal home life, desiring domesticity above all else, but swallowing her pride when she needs to go out to work in a night club to make ends meet, for a time rendering the unemployed Eddie a house husband.

But Eddie is not all he initially seems. His tough streak has not been smothered by the good life. In a brilliant Catch-22 situation he gets violent when an employment benefits clerk refuses to accept that Eddie was fired from his job, instead believing his employer’s claim that he resigned – the former triggering relief payment, the latter zilch. But that’s nothing to the beating he administers to Kristine when, pride injured that he is not the breadwinner, he discovers the skimpy costume she wears for her job.

Adding to the unusual mix are Vido and Walter, the former’s brooding presence somewhat undercut by the fact that in middle age he still lives with his mother, the latter while a big-time gangster letting nothing get in the way of strong fraternal feeling for Eddie.

You won’t be surprised to learn double cross is in the air, not when Walter employs a creepy sunglass-wearing henchman Sargantanas (John Davis Chandler) who appears to have more than a passing interest in little girls. The climax, which contains both emotional and dramatic twist, involves redemption and sacrifice.

Delon has played the cold-eyed ruthless but romantic character before, but here adds depth from his paternal commitment and as a man turned inside out by the system.

Ann-Margret is the revelation, truly believable as mother first, sexy wife second, and her anguish in the later parts of the picture showcase a different level of acting skill to anything she previously essayed. This role immediately preceded her man-eater in The Cincinnati Kid (1965) which attracted far more attention and considerably bigger box office and it would been interesting to see how her career might have panned out had Once a Thief been the critical and commercial triumph. She probably did not attain such acting heights again until Carnal Knowledge (1971). And I did wonder, as with Daliah Lavi (The Demon, 1963) before her, whether her acting skills were too often overshadowed in the Hollywood mindset by her physical attributes.

Van Heflin (Cry of Battle, 1963) is excellent as the cop tormented by the idea that a villain is walking free, Jack Palance (The Professionals, 1966) is good as always and character actor Jeff Corey (The Cincinnati Kid) puts in an appearance as Vido’s whip-cracking boss and this marks the debut of Tony Musante (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970). Watch for a cameo by screenwriter Zekial Marko (Any Number Can Win, 1963) , who wrote the original book.

This represented another change of pace for director Ralph Nelson, Oscar-nominated for the Lilies of the Field (1963) and also known for box office comedy hit Father Goose (1964). His use of an experimental, more light-sensitive, camera eliminated the bulky lighting commensurate with filming at night, bringing freshness and greater freedom to those scenes. His natural gift for drama ensured that the emotional was given as much prominence as the action. Racial awareness was demonstrated by the opening scene in a jazz club where African Americans were clearly welcome, hardly the norm at that time.

Mention again of a terrific score by Lalo Schifrin, especially the bold drum solo that played out over the credit sequence.

Top-notch.

One thought on “Once a Thief (1965) ****”