Astor had yanked La Dolce Vita from the Henry Miller Theatre in December 1961 perhaps a bit prematurely but, unless willing to wait until spring when another arthouse became free, it had nowhere else to put Les Liaisons Dangereuses, which had performed extremely well in its native France with 639,000 admissions.

Anxious to get this latest hit, the Henry Miller Theatre had offered a fat guarantee. Although only 1¾ hours long, compared to the three-hour La Dolce Vita, it was launched as a roadshow, with three performances a day, at 2.30pm, 7.00pm and 9.30pm. This was an equally controversial film; it only managed 10 days play in February in New Jersey before being closed down by the authorities, although by then it had been seen by 7,500 customers.

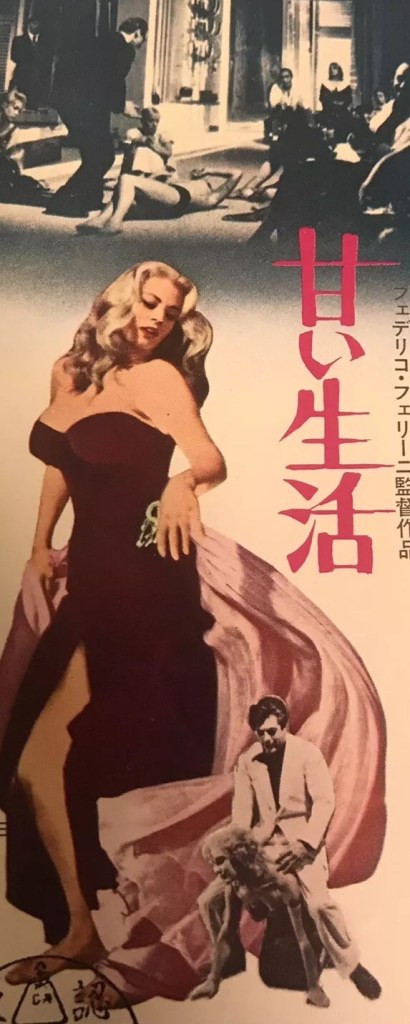

Believing there was a lot more juice left in the Fellini film, Astor acquired all the worldwide rights, including all existing contracts with current distributors, for $1.35m. The film had not yet been released in Latin America, which was expected to provide strong box office. This proved correct; for example, it grossed $100,000 in Chile. Despite not being entered in the foreign film category of the Oscars, La Dolce Vita managed nominations for best director, best screenplay, best art direction and best costume design, for which it won. Nino Rota’s music was nominated for a Grammy.

In the summer, Astor continued to expand, acquiring the Pathe American distribution company, a deal which included 18 unreleased films such as Bryan Forbes debut feature Whistle Down the Wind. The purchase was part of a broader strategy to give Astor a deeper penetration of the market, guaranteeing them better playoffs for their own films. Even so, questions were beginning to be asked of the company’s financial situation. President George Foley complained: ‘People seem to have the knife in us.’ He explained that, in the wake of the company’s explosive growth from a turnover of $500,000 to $4m it was guilty of over-ambition, and it was trading profitably.

But that was not correct and soon the company required a $1m loan. Negotiations dragged on and when they were concluded in August, the loan granted by the Inland Credit Co was only half that requested.

However, La Dolce Vita remained a cash cow. After completing a 34-week run at the Henry Miller Theatre in December, it transferred to two cinemas in New York, the Embassy and the Beekman, where, with lower admission prices, it took an astonishing $44,500 in its first week. Thereafter, it shifted to 15 neighborhood cinemas in New York. Its longevity was assisted by the shortage of mainstream product created by the major studios investing so much money in roadshows. That meant the big studios made fewer feature films, leaving exhibitors scrabbling to fill playdates. Some cinemas survived by extending the playing period of existing bookings, but for other cinemas, accustomed to a weekly change or lacking the audience-base to support films running for two or three weeks, this was impractical.

More and more local cinemas turned to foreign movies. Often these movies, sometimes helped along by lurid titles, received the saturation treatment previously given to horror or science-fiction films. La Dolce Vita was able to take advantage of these changes in exhibitor strategy. But where you might have expected a subtitled film to play at the bottom of a double bill (local theatres always showed two films), more often than not La Dolce Vita was by that time so well-known that it was advertised as the main feature.

By September it had clocked up 3,000 bookings, a record for a subtitled film, and expected at least another 2,000 before the well ran dry. It also started to be reissued, turning up in programmes with A Cold Wind In August and Two Women. At year’s end it was Joe Levine’s turn to crow. Two Women was the top foreign film of the year and with a gross of $6m took 30th position at the annual box office race.

By now Astor’s rapid expansion was taking its toll. Ironically, La Dolce Vita, the gamble that had succeeded beyond anyone’s dreams, had inspired too many other gambles that had failed. In the old days, the revenues generated by Anotnioni’s Rocco and His Brothers and Vadim’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses would have put them in the category of hits. While favoured by the critics, the Italian film did not fare well at the box office. The Vadim film, hampered by a Condemned rating from the Production Code and by mixed reviews, managed only 300 bookings and ended up costing Astor $500,000. Last Year at Marienbad had only managed a $350,000 gross.

Not only did none of the films replicate the success of La Dolce Vita, they did not justify the amounts Astor had paid for them. In January 1963 Inland Credit announced a public auction of Astor’s assets. This crisis was quickly resolved with a new loan repayment schedule. There were no irregularities involved, just an inexperienced company diving into the acquisition market with too much enthusiasm. Having quit its plush offices in Madison Ave and cut back on staff, Astor remained optimistic. The cash cow La Dolce Vita was not dead yet and in February was reissued again, this time in a double bill with British film Victim starring Dirk Bogarde, on the RKO circuit in New York.

There were high hopes for the adaptation of the Brendan Behan play The Quare Fellow and The Black Fox. Better, there was a new full-length Fellini on the horizon. Based on its first six weeks in Rome and Milan, where it notched up $320,000, the producers of 8½ were projecting an Italian gross of $3m. Astor had marked out June for its US premiere.

But Astor did not make it to June.

In March, Inland Credit called in its loan. Astor battled this in court, but the judgement went again them. The company which had single-handedly launched arthouse films into the mainstream was out of business. The rights to La Dolce Vita were acquired by Landau-Unger, who had made the American arthouse hit The Pawnbroker starring Rod Steiger. But their reissue of La Dolce Vita in 1965 was underwhelming and they sold on the rights to AIP, another company which saw marketing foreign films as the way to mainstream credibility. AIP was famous for horror and exploitation films and for turning out both on ludicrously short shooting schedules. It had ransacked almost the entire portfolio of Edgar Allan Poe for Fall of The House Of Usher, The Pit And The Pendulum, The Premature Burial and The Raven.

Fellini, of course, had an unassailable name at the arthouse box office. While 8½ attracted neither the critical kudos, although it did receive an Oscar nomination and took the BAFTA for best foreign film, nor the box office of its predecessor, it was still good for $3.6m gross. Counting the grosses of 8½, La Dolce Vita, La Strada and his share of Boccaccia 70, Fellini was, with De Sica, the top foreign filmmaker. De Sica added his box office clout to that of Loren in The Condemned of Altona and Marriage Italian Style, which won Loren another Oscar nomination, and in Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, which was named Best Foreign Film in 1965 at the Oscars.

Like Astor, AIP was not a company that played by the rules. In 1966, it decided to reissue La Dolce Vita in a dubbed version. One of the main reasons for this was to achieve a sale to television, a medium still hostile to subtitled films.

The dubbed film went against Astor’s original agreement with the National Legion of Decency (now re-named the National Catholic Office of Motion Pictures), but by now there were more contentious films on the market. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf had gone out with a ‘no under-18’ policy. And the Production Code’s A+IV classification (morally objectionable for adults but with reservations) had been slapped on Alfie, 8½, Tom Jones and The Servant. So AIP sidestepped a Legion condemnation by agreeing to a ‘recommended for adults’ advertising campaign and accepted the Code’s A+IV classification.

Quite why AIP chose two cinemas in Virginia and Oregon, respectively, to launch the new dubbed version is anybody’s guess. Perhaps it was inexperience, or a belief that the movie was played out in the bigger cities, or market hostility to a company best known for a different product. Or maybe this was simply a tactic to generate television interest, similar to the way some movies are released these days for a week in cinemas to fulfil a contract prior to DVD release. Eventually, however, La Dolce Vita found its way to its spiritual home, an arthouse in a big city and in its opening week at the 868-seater Four Star in Los Angeles in October it took a ‘socko’ $10,000. And like Astor before it, AIP found it had a bigger hit on its hands than it could imagine when the dubbed version took another $3m.

The tactic worked and next year La Dolce Vita was screened on television, with, once again, astonishing results.

In November, on the independent WOR-TV station, it swept aside in the ratings a Frank Sinatra special and I Spy. Unsurprisingly, the network served up the dubbed version. But there were a few eyebrows raised at the bowdlerisation. ‘Homosexual’ was changed to ‘depraved’ and ‘fascist’ to ‘scandal’. By then, the arthouse movie was rejuvenated by movies like Elvira Madigan, A Man and A Woman and Belle De Jour. But La Dolce Vita was the one that had opened to the door for arthouses movies into the mainstream and it was fitting that by the end of the decade it was declared the foreign film champ of all time with a gross that had risen to $15m.

In my exclusive chart of The 1960s Top 100 Movies according to US box office it was ranked 91st, above such films as To Kill A Mockingbird, Blow Up, Where Eagles Dare, Cool Hand Luke, The Thomas Crown Affair and The Pink Panther. Even to people who never visited an arthouse cinema, Fellini was a household name and the term La Dolce Vita passed into the general vocabulary.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, La Dolce Vita and the American Box Office Bust-Out (Baroliant, 2018) ; “Brian Hannan Revisits La Dolce Vita,” Cinema Retro, No 33.

Wow, had no idea this got such an early tv release, that seems quite extraordinary….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Clever people at AIP.

LikeLiked by 1 person