La Dolce Vita opened in New York and Boston the same day – April 19, 1961 – and smashed the first day record in both cinemas. And the weekly record. In truth, given the hype, and the increased ticket prices, that was no surprise. But whereas La Dolce Vita made $16,000 in its first week in New York and $35,000 in Boston, Mein Kampf made $87,000 in New York. In the 1960s, movies lasted in cinemas far longer than they do now. And that kind of longevity cannot be maintained by advertising alone. The two most powerful tools in giving a film ‘legs’ were word-of-mouth and the critics, who could make or break a movie in a way that is impossible these days.

Reviews were superlative. ‘Awesome but moral,’ commented the New York Times. ‘Brilliant’, ‘outstanding’, ‘a masterpiece’, seemed to be the consensus. Another powerful opinion-maker, in that it was her business to put her money where her mouth was, Helen Thompson, bought out 25 complete shows for her Play-of-the-Month club. There were sell-out performances in New York and Boston, but would the rest of the country fall in line?

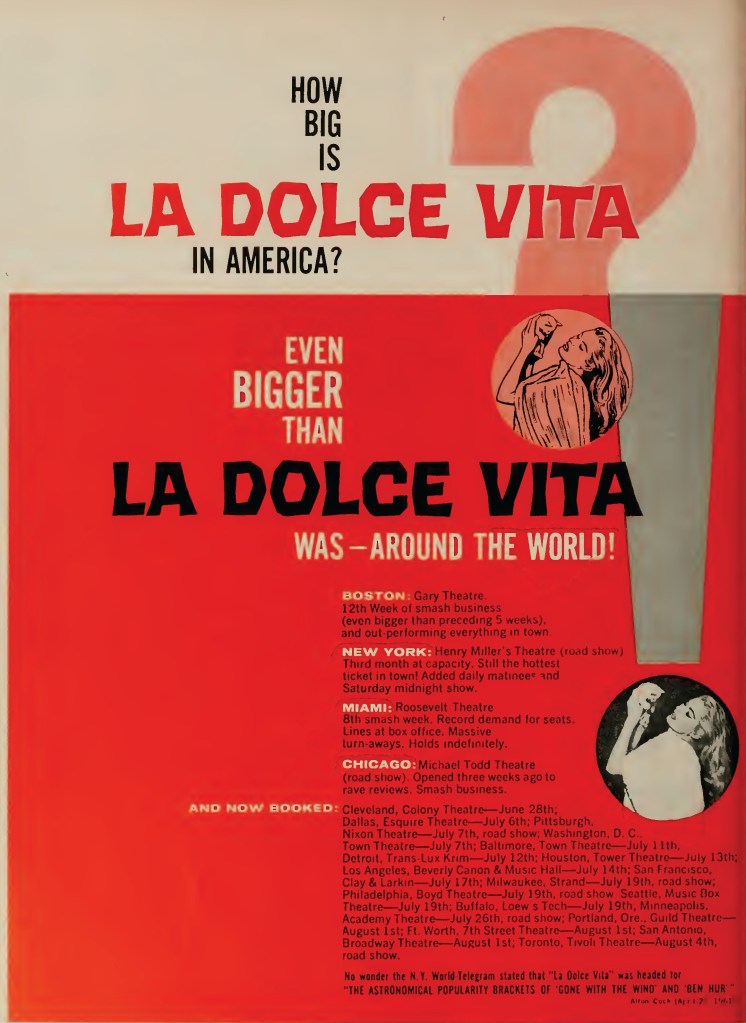

In an attempt to create a bidding war, Astor screened the movie for 25 cinema owners from the big cities. The Todd Theatre in Chicago was chosen as the next venue, also as a roadshow, but that was for a limited period only and when it moved onto continuous performances (called ‘grind’), it set a new high for ticket prices – $2.50 compared to the previous record of $1.80. In Los Angeles, Herbert Rosenor, owner of two arthouses, guaranteed $75,000 and an eight-week minimum run.

Despite breaking so many rules in the launching of La Dolce Vita, there was one rule that remained sacrosanct.

In the 1960s, delay, which in turn created heightened anticipation, was a powerful marketing tool. It was used by the major studios to build demand for their roadshows. So it did no harm that the rest of America had to wait for La Dolce Vita.

It took three months for the film to reach Los Angeles. On arrival it shattered all records, taking in upwards of $30,000 between the two cinemas. And its first weeks elsewhere that July achieved similar results – $17,000 in Pittsburgh, $14,000 in Baltimore, $26,000 in Detroit. Astoundingly, it was keeping pace with the year’s biggest blockbuster The Guns of Navarone. In its 25th week at the Henry Miller Theatre, La Dolce Vita registered $25,000 while The Guns of Navarone in its 6th week at two cinemas took a combined $66,000. In the first week of both films in San Francisco, the war film made off with $32,000 at one 1,400-seater while the art film scrambled £28,000 at two 400-seat cinemas, and both had the same top price of $2.

In Baltimore, the second week of La Dolce Vita beat the second week of The Guns of Navarone. In the weekly national box office chart compiled by Variety, which covered the 24 US major cities, La Dolce Vita notched up fifth position. By August it was fourth and then third.

Ancillary marketing helped. RCA issued the soundtrack album, which included the sensuous theme as well as Rota’s adaptations in the movie of standards like “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby” and “Jingle Bells.” While the album reached the lower echelons of the Top 50 album charts for several weeks, which, for an arthouse film would be considered an excellent result, it was overshadowed by its biggest competitor Never on Sunday, which spent over a year there, reaching the top five. Ballantine publishers brought out a paperback of the screenplay with 200 stills.

Controversy was milked when Atlanta threatened to boycott the movie and the Los Angeles Times censored an advert, blacking out most of a prostrate girl with her hands on her breasts. Clubs began springing up calling themselves La Dolce Vita. Archbishop William Scully launched a campaign to prevent its showing in Albany. ‘Pass this one up for the good of you soul,’ he intoned. Getting equal press attention was a review in The Presbyterian Life which called it ‘a highly moral movie.’ The media latched onto news reports that the tossing of coins into the Trevi Fountain in Rome had trebled.

To prove it was not a one-hit wonder, in July Astor launched its follow-up movie, another Italian film, Rocco and His Brothers, directed by Luchino Visconti. This had been a box office sensation in Italy, earning over $625,000 in its first year, and the rights had cost $325,000.

Astor had made three versions – subtitled and dubbed versions of the full 175-minute film and an edited 145-minute dubbed one. Now that Astor was a proven success, cinemas opened up to them and it was able, this time, to launch the Visconti film on two cinemas, the Beekman and the Pix. The film was launched on June and broke records at both cinemas, with $15,000 at the Beekman. Using a promotional technique borrowed from La Dolce Vita, to coincide with the launch the company released a single, “The Ballad Of Rocco”, even when there was no such song in the movie, following up with the original soundtrack, by Nino Rota, in August.

With other backers from Italy and France, it was financially involved in a planned remake of the Hedy Lamarr 1930s sensation Ecstasy and was in negotiation with the new pretenders to the Italian artistic throne, Michelangelo Antonioni and Luchino Visconti.

Astor purchased India by Robert Rossellini and, as if not wishing to lose trace its roots, The State Department Murders and were hoping to conclude a deal with Russell Hayden for three pictures. Having been pipped by Joe Levine to Boccaccia 70, a compendium of short films directed by Fellini, Visconti, De Sica and Mario Monicelli and starring Loren and Ekberg, Astor turned towards the French New Wave.

George Foley snapped up Roger Vadim’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses, so controversial no other distributor had gone near it since its launch in September 1959, Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad and the new film from Francois Truffaut, hot after Breathless and 400 Blows, Shoot the Pianist. The company moved into prestigious offices in Madison Avenue and recruited more staff including Douglas Netter who joined as international president from Samuel Goldwyn’s head office. Soon it would set up a literary department, its first purchase The Only Reason by Tereska Torres, which, since it was set in Paris, was being proposed as a future project for Vadim. Confidently mapping out the company’s direction, Foley said, ‘In coming years we foresee co-productions in every major picture-producing locale where satisfactory projects can be created.’

Gradually, Astor achieved its ambition of expanding La Dolce Vita beyond its core audience in the big cities. Mastroianni embarked on a 28-city promotional tour. On October, a double-page advert in Variety announced: ‘All over American cities and towns, theatres that have never played a subtitled picture before are doing terrific business with La Dolce Vita.’

The advert listed cinemas in previously unimaginable locations for an art film such as Little Rock and Hot Springs, Arkansas, Wilmington in Delaware, Macon in Georgia, and Dodge City in Kansas. In all, 162 cinemas had shown the film including nine roadshows, all still running, and nine modified roadshows. The top roadshow run was in New York (27 weeks). The roadshows totalled 121 weeks including stints in Chicago, Miami, Philadelphia, Milwaukee, Minnesota, Toronto (US grosses always include Canada), New Jersey and Vancouver. Astor had bookings for another 134 cinemas.

Towards the end of the year, it started moving into neighborhood theatres where, at lower prices (called ‘popscale’), it played extended runs. In London, after ending its run at the Curzon, La Dolce Vita transferred to the Berkeley where it ran for another 20 weeks, and then went on national release through the National Circuit cinema chain. Its 34th and final week, in December, at the Henry Miller Theatre generated $10,000. In Italy, it was bracketed with Ben Hur as the top film of the 1960-61 season, beating the Hollywood epic in several cities including Milan.

When all the US figures were in, La Dolce Vita proved the most successful gamble of the year, the three-hour arthouse epic turning into a massive mainstream hit well beyond even the most optimistic expectations of the ambitious Astor, taking in an astonishing $9m (gross not rental).

It ranked 12th on the 1961 box office chart, above other big-risk movies like One Eyed Jacks and Cimarron. It finished ahead of Paul Newman in The Hustler, Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, John Wayne in North To Alaska, Elvis Presley in Blue Hawaii, Never On Sunday and Mein Kampf. In that nationwide list, The Guns of Navarone came top, with The Alamo 5th and The World of Suzie Wong 8th. But in the placings for Los Angeles, La Dolce Vita came 5th, beating all three. Of course, the cognoscenti claimed it was a fluke. But the simple riposte to that was that every hit film was a fluke, otherwise the supposedly wiser Hollywood heads who had committed millions in One Eyed Jacks and The Alamo would have been left celebrating, rather than ruing, their investment.

Come the year end, La Dolce Vita was on every critics top ten list, if not the film of the year. It was named best film by the National Board of Review and the New York Film Critics Circle. It should have been a shoo-in for the best foreign film Oscar. In fact, it was not put forward, as the nomination was done by the Italian government, which believed, bizarrely that La Dolce Vita had won too many awards, and it was someone else’s turn.

Everyone involved, however peripherally, in La Dolce Vita wanted to build on its success. Columbia, for example, released La Verite starring Brigitte Bardot in the same Columbia/Curzon duet in London but its first week had brought in only a combined $13,500. But Omat soon faded from the marketplace. Other majors like 20th Century Fox were inspired to invest in European films, most notably The Condemned of Altona, starring Loren, and Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard starring Burt Lancaster.

Meanwhile, Embassy had not conceded defeat on the arthouse front. Joe Levine knew only too well, from his success with Hercules, how to parlay an investment in a foreign film into gold at the American box office. And it was clear to him that Astor had copied his marketing techniques to turn La Dolce Vita into an enormous success.

So he cast around for another foreign film. He found it in De Sica’s Two Women. This toplined Sophia Loren who had the added benefit of already being a marquee name in the US, having starred with top names like Alan Ladd in Boy on a Dolphin, Frank Sinatra in The Pride and The Passion, John Wayne in Legend of The Lost, William Holden in The Key, and more recently, Houseboat (which, incidentally, produced another hit single) with Cary Grant.

Noting the success of the English-language Never On Sunday, Embassy was canny enough to make a dubbed version of this film. Of course, for the sake of appearances, a subtitled version was also available, but, inevitably, the bulk of cinema owners, especially outside the big cities, opted for the dubbed version. When Sophia Loren was nominated for the Best Actress Oscar in spring 1962, Levine capitalised on the publicity. She was far from being the favorite. She was the unexpected victor and, naturally, her win boosted bookings and, by association, conferred on Levine the mainstream recognition he craved.

Boccaccio 70 produced another fierce bidding war, this time just between Astor and Embassy. Levine was determined not to lose another prized asset. Again, Levine broke the rules, and on the strength of the directors and stars, pre-sold the movie to distributors in various countries. By the time the film opened, he reckoned he would have already broken even, before he received his share of the profits.

His boldness reached new levels. The four directors in the film had each made a segment that last one hour. He toyed with the option of releasing the movie in two parts. In the end, he simply chopped out the least well-known director Mario Monicelli, leaving him with a three-hour movie. Not only did he intend to present Boccaccio 70 as a roadshow, but it would have two intermissions instead of one, so that each section would be seen afresh.

His new-look company also had two films by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, who had just won the Best Foreign Film Oscar for Through the Glass Darkly, lined up for distribution and Il Bel Antonio starring Claudia Cardinale and Mastroianni. Already involved, with various partners, in the production of Italian movies, he now had American movies in development. In total, he had committed nearly $10m to Sodom and Gomorrah, Boccaccio 70, The Wonders of Aladdin and Boys Night Out, for which he was paying star Kim Novak $500,000. In addition, he was planning a big budget roadshow film about the San Francisco earthquake plus psychological thriller Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (he pulled out of this after a row with director Robert Aldrich) and The Carpetbaggers (made for Paramount).

Every bit as bullish as Astor, he announced, ‘I want theater owners all over the world to know this is the kind of schedule they can expect from me.’

Until now the director had been the prime tool for marketing arthouse films, but La Dolce Vita and Never On Sunday threw up, for the first time, actors, in the shape of Mastroianni and Melina Mercouri, as dependable marquee names. They became ‘bankable’ names for European producers looking for a guarantee of selling their films to an American audience. Mastroianni appeared in most of the films by the big Italian directors while Mercouri was absorbed into the mainstream in films like The Victors and Topkapi. Fellini, of course, now the biggest box office draw in foreign films, could more or less write his own ticket. He was in talks to make his first American movie, but not with Astor. Instead, he opened negotiations with the Mirisch Brothers, who were known for entering into deals that actors and directors found profitable.

Part Three tomorrow.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, La Dolce Vita and the American Box Office Bust-Out (Baroliant, 2018) ; “Brian Hannan Revisits La Dolce Vita,” Cinema Retro, No 33.

Didn’t even know there was a film of Mein Kampf, but looked it up and there it is, every day’s a school-day…

LikeLiked by 1 person

And it may be coming soon to a blog near you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would be wrong for me to express too much enthusiasm for Mein Kampf….

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a struggle.

LikeLike