Two trends came together to create the ideal climate for the movie. The first was a fashion for filming comic books. By the mid-60s, Italy was at the forefront of this development thanks to the fumetti craze.

Mandrake, created in 1934 and first filmed in 1939, was being prepped by Duccio Tessari (My Son, the Hero, 1962). Though that stalled on the starting grid Dino De Laurentiis had bought the rights to Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella. He was also prepping Diabolik – at that point to be directed by Brit Seth Holt (Station Six Sahara, 1963) and fronted by Catherine Deneuve (Belle de Jour, 1967). Monica Vitti was being lined up to play Modesty Blaise (1966). For Barbarella De Laurentiis initially favored Franco Indovina (The Oldest Profession, 1967) in the director’s chair and Brigitte Bardot as the star.

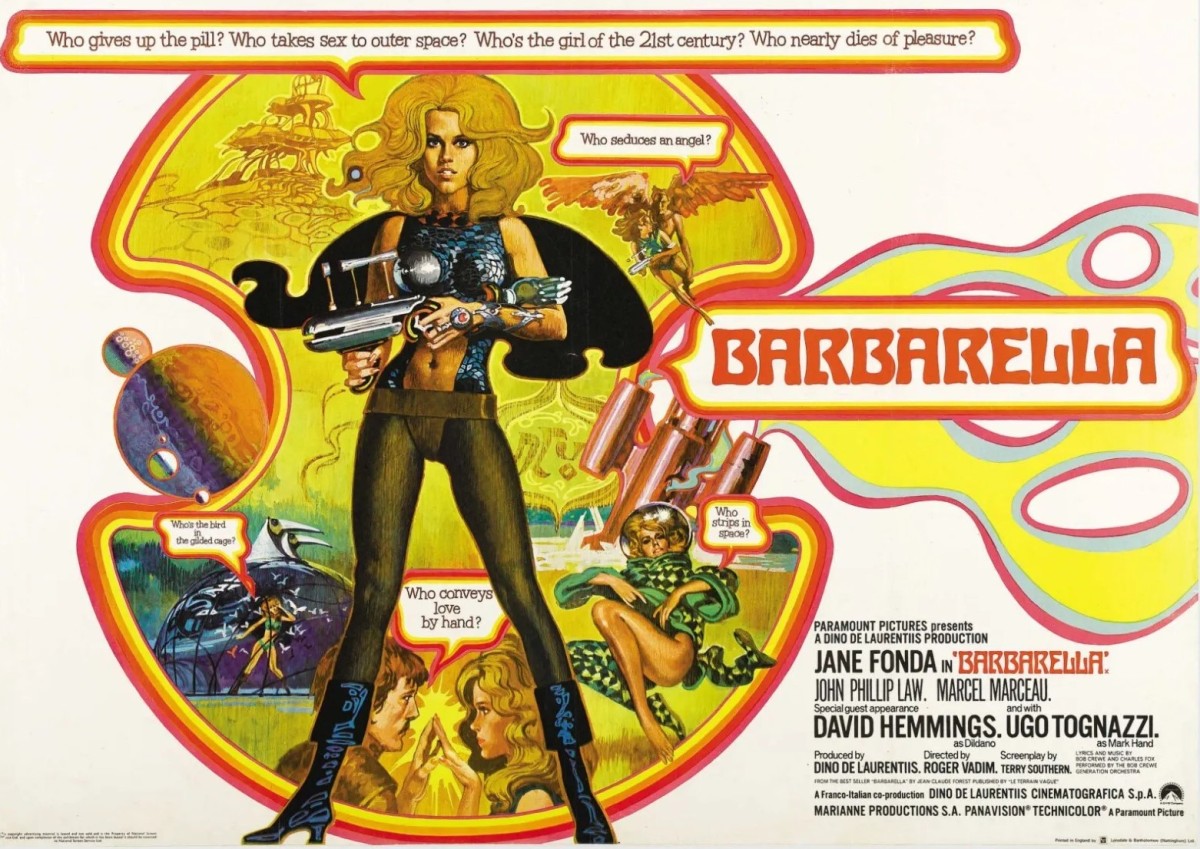

The other element driving forth the venture was the involvement of Hollywood major Paramount in European production. Paramount had turned to Europe to “replenish its dwindled film vaults.” Formerly almost exclusively committed to U.S. production, by 1967 the studio was in the middle of a $60 million European spending spree, the cash spread over 30 movies made in the U.K. or mainland Europe where Italy took the lion’s share. Paramount struck a deal with De Laurentiis for Barbarella and Danger: Diabolik (1968) – eventually helmed by Mario Bava with John Philip Law and Marisa Mell – plus Arabella (1967) and Anzio (1968).

Paramount’s involvement should have excluded Vadim. He was persona non grata with the studio, having reneged on a previous three-picture deal, which he was paying off in $20,000 instalments. The budget of $3 million should have put the picture out his league. The Game Is Over had cost only $900,000 and none of his previous work suggested he might have the necessary skill to handle the special effects. And he was well known for declaring his opposition to studio interference.

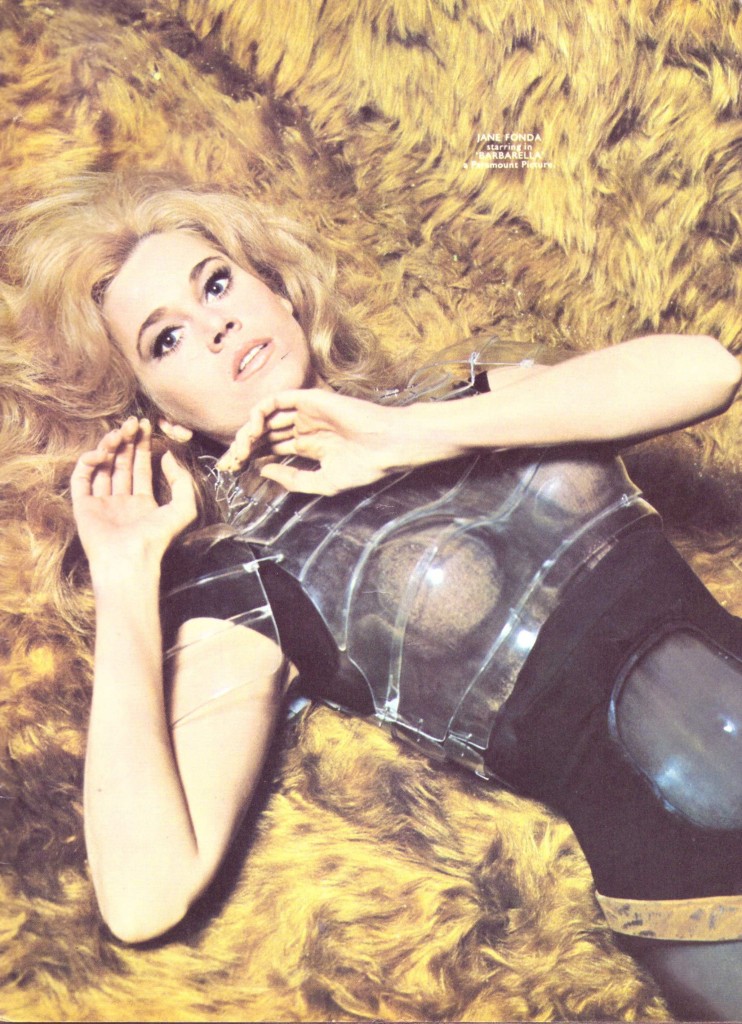

But in terms of delivering sexy fare Vadim was in a class of his own. And God Created Women (1956) was the top-earning foreign picture in the U.S. He had made stars of Brigitte Bardot and Annette Stroyberg (Dangerous Liaisons, 1959) and he was in the process of turning the earnest Jane Fonda (In the Cool of the Day, 1963) into a sex symbol after plastering her nude body over billboards promoting La Ronde/ Circle of Love (1964) and stills from La Curee/The Game Is Over in Playboy.

Still, she was far from first choice. Following Bardot’s refusal, De Laurentiis approached Sophia Loren, but she was pregnant, and he did a screen test of Ira von Furstenberg (Matchless, 1967). Fonda was not as nailed-down a star as you might expect. Her affair with Vadim kept her out of the country, making the kind of picture that was generally perceived as salacious arthouse material and not likely to raise her marquee value in the U.S. Cat Ballou (1965), which should have propelled her to the very top, instead performed that trick for Lee Marvin after he won an Oscar for the dual role. After meaty roles in The Chase (1966) and Hurry Sundown (1967) and top-billed in comedy hit Barefoot in the Park (1967), she should have been able to write her own ticket. But she did demonstrate independence in choosing to align with Vadim for Barbarella and though it didn’t win her any acting accolades it smoothed the path towards They Shoot Horses, Don’t They (1969) and Klute (1971), for which she won the Oscar.

Vadim was smarting from damage done to his reputation by censors and the authorities. “I have become a black sheep for censors and I’m paying the penalty in everything I make. Anything I direct is automatically suspect. I believe I’m the only director who must get censor clearance before I can begin filming.” He wasn’t – technically, this applied to every director working Hollywood since all scripts had to be cleared in advance of filming by the Production Board. But in Italy even when films like The Circle of Love (1964) and The Game Is Over (1966) cleared censorship obstacles, the films were seized by the police and threats laid of obscenity charges.

However, he believed this time round he would be immune from threat since the film would contain “no reference whatsoever to moral concepts as we know them. We’re dealing with life in the year 40,000. It would be difficult in the realm of science fantasy for any censor to discover objectionable scenes.” Clearly, he assumed mere nudity would not raise eyebrows.

Vadim admitted, “When I made Barbarella, I found the most difficult thing was the detail.”

Attracted by the “wild humor and impossible exaggeration” of the original material, he “wanted to make something beautiful out of eroticism” and intended to film it as if “a reporter doing newsreel…as though I had just arrived on a strange planet.” And had a camera on his shoulder. He viewed the character as a “lovely average girl” though not so average in that she possessed “a lovely body.”

Fonda was determined to keep her character “innocent,” rejecting the idea of playing her as a vamp, “her sexuality was not measured by the rules of our society,” and neither “promiscuous” or “sexually liberated.” Vadim interpreted her role somewhat differently, viewing it through the prism of a “shameless exploitation of her sexuality.”

With multiple writers on the project, the question of who wrote what has been open to argument. Impressed by their work on Danger: Diabolik – which employed a total of eight screenwriters – De Laurentiis parachuted in British pair Tudor Gates and Brian Degas. Original writer Terry Southern (Candy, 1968) claimed responsibility for the opening striptease and the doll robots. Uncredited screenwriter Charles B. Griffiths (The Wild Angels, 1966) came up with the notion of the millennia of peace, Barbarella’s clumsiness and the suicide room. Even co-star David Hemmings got in on the act, claiming he inspired the nonsense Fonda spouted during their sex scene.

Southern suggested Anita Pallenberg for the role of the Black Queen after encountering her while working with The Rolling Stones – her voice was dubbed by plummy English actress Joan Greenwood. Jane Fonda brought John Philip Law into the equation after working with him on Hurry Sundown (1967).

The director employed some sleight-of-hand. Just like the later Ridley Scott on Alien, he didn’t inform his actors in advance what was about to happen in some critical scene, such as those involving the Excessive Pleasure Machine. Vadim wanted a natural response from Fonda and Milo O’Shea so omitted to tell them “what a big explosion there would be. When the machine blew up, flames and smoke were everywhere, and sparks were running up and down the wires.” Fonda was “frightened to death” and O’Shea was convinced he “was being electrocuted.

And Vadim summoned his inner Hitchcock for the scene when Fonda was attacked by the hummingbirds (actually, substitute wrens and lovebirds). Not getting the effect he wanted, Vadim used a powerful fan to blow the flock onto the actress whose outfit was peppered with birdseed. There was an unexpected two-week hiatus between filming the bird attack and the striptease. Fonda contracted a fever, forcing the movie to shut down halfway through its 12-week schedule. On her return, Vadim filmed the striptease to be shown over the credits which was intended to “camouflage censorable flesh.” The set for the strip was upside down, Fonda performing on a pane of glass facing a camera in the ceiling.

The sensational aspects of the movie had attracted exceptional media interest. Over 200 journalists visited the set including representatives from Vogue, Playboy, Time, Life, McCall’s, Seventeen, Paris Match and UPI and AP. Paramount kept the pot boiling with some advertisements that were exceptionally full-on for the times: “It’s the year 40,000 A.D. A scantily-clad space adventuress battles 2,000 hummingbirds who rip off her clothes, two dozen shark-toothed dolls who rip off her clothes, 100 purple rabbits who don’t rip off her clothes and an army of leather giants who attempt to whip her to death. In between she makes love a lot.”

By the time the movie appeared, Paramount had invested in another development. It was the first studio to set up a marketing department, not just a catch-all under which promotional and advertising efforts were undertaken, but a unit that took a systematic, research-based, approach to release strategy. As a result Barbarella was one of the first movies to achieve a global simultaneous release, the bulk of movies taking a step-by-step approach, U.S. first and then major countries overseas, following a pattern that could take up to 18 months to complete.

According to research undertaken by the marketing department it was “judged as a picture which would have a sensational first few weeks everywhere it played because of the impact of the subject matter, star (Jane Fonda) and promotional pizzazz. But research indicated word-of-mouth might be poor. The decision was made to open the picture everywhere at once – and that meant worldwide since there was fear that any ‘bad word’ on such a highly-touted pic could spread from country to country. Here, too, the prognosis proved letter-perfect. As any exhibitor will confirm, Barbarella was the film this fall which started out great then dropped off. In view of this Paramount is thought to have maximized its gross via the global saturation playoff pursued.”

In the U.S. Paramount ordered a record number of trailers and space age fashion shows, like one at Alexanders Department Store in New York, were the order of the day. In Britain, there was a phenomenal ad spend (the second-highest ever), Mary Quant boots, tie-ins with shoe stores, and both a hardback and paperback book.

But Barbarella proved to be a slow-burn at the box office. Initially, it was deemed to have ranked a lowly 46th in the annual U.S. rentals chart with just $2.5 million in the kitty, falling far short of Paramount’s box office smashes that year – The Odd Couple (ranked fifth) with $18.5 million in rentals and Rosemary’s Baby (ranked seventh) on $12.3 million. But, in fact, it more than doubled its rentals the following year and ended up with a highly-respectable $5.5 million at the U.S. box office. (And I hereby apologize to anyone whom I challenged on these figures).

The global release paid off. It ranked eighth in France, seventh in Switzerland, third in Britain, 14th in Hong Kong and a big hit in Italy. However, the content denied it a sale to U.S. television. The movie was reissued in 1977 in the wake of Star Wars, and took a “handsome” $175,000 gross from 65 houses in New York. It was revived again after Flash Gordon (1980) and the following year when Paramount entered the laserdisk business among the first 30 oldies released it was the only one from the 1960s.

A sequel’s been on the cards since the film opened. Possibly rather tongue-in-cheek and with an element of the risqué sauce of the times, Paramount’s Robert Evans planned to trigger a second episode called Barbarella Goes Down, the title apparently relating to underwater adventures. Terry Southern was asked to write a sequel in 1990 while in the aftermath of Sin City (2005) director Robert Rodriguez came close to an $80 million version and Nicolas Winding Refn toyed with a television series. As of now, Sydney Sweeney (Anyone But You, 2023) appears most likely to hit the sequel button.

SOURCES: Patrick McGilligan, Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 60s, (University of California Press, 1997); Lisa Parks, “Bringing Barbarella Down to Earth”. In Radner, Hilary; Luckett, Moya (eds.). Swinging Single: Representing Sexuality in the 1960s, (University of Minnesota Press, 1999); Gail Gerber,and Gail Lisanti, Gail (2014). Trippin’ with Terry Southern: What I Think I Remember. McFarland, 2014); Roberto Curti, Diabolika: Supercriminals, Superheroes and the Comic Book Universe in Italian Cinema (Midnight Marquee Press, 2016); .Brian Hannan, Coming Back to a Theater Near You, A History of Hollywood Reissues 1914-2014 (McFarland 2016) p252; “Comic Strip Character Film Trend,” Variety, June 9, 1965, p23; “Vadim’s Autonomous Views,” Variety, August 24, 1966, p2; Gerald Jonas, “Here’s What Happened to Baby Jane,” New York Times, January 22, 1967; “Paramount Getting 6 Pix from Italy in Bid to Build Prod,” Variety, February 1, 1967, p16; “Par O’Seas Hatch By Dozen,” Variety, April 26, 1967, p5; “Italo Film Boom,” Variety, June 7, 1967, p20; “Barbarella Laid Low By Jane Fonda Virus,” Variety, August 16, 1967, p2; “I’ve Been A Black Sheep To Censor,” Variety, July 19, 1967, p22; Marika Aba, “What Kind of Supergirl Will Jane Fonda Be as Barbarella?” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1967; Roger Ebert, “Interview with Jane Fonda,” October 15, 1967; “Paramount Stressing Sex and Visual Fantasy,” Variety, October 18, 1967, p26; “Space Age Fashion Show,” Box Office, September 2, 1968, pA2; “Record Teaser Trailer,” Box Office, September 9, 1968, p13; “Eyebrows Up – Here’s Barbarella,” Kine Weekly, October 19, 1968, p23; “Big Box Office Winners of 1968,” Kine Weekly, December 14, 1968, p6; “What Makes a Director?”, Variety, January 8, 1969, p26; “Big Rental Films of 1968,” Variety, January 8, 1969, p15; “Swiss B.O. Race,” Variety, January 15, 1969, p41; “Shaws Dominate HK,” Variety, January 15, 1969, p41 “Par Puts the Science into Sell,” Variety, February 5, 1969, p33; “Int’l Filmgoing Tastes Tres Complex,” Variety, February 5, 1969, p35; “CBS Bid for Baby Doll,” Variety, October 29, 1970, p78; “All-Time Film Rentals,” Variety, January 7, 1970, p27; “New York Showcases,” Variety, November 2, 1977, p8; “Paramount’s Home Video to Market Viddisks,” Variety, April 29, 1981, p54.

Apology accepted. I think Diabolik is actually a better movie, but Barbarella certainly looks good as wallpaper, rather than as a gripping story, which is is not.

LikeLiked by 1 person