Call it friendly persuasion. After The Magnificent Seven (1960), producer Walter Mirisch wanted to keep director John Sturges on-side. Other potential projects were falling by the wayside and Sturges needed, for financial reasons, to keep working while Mirisch wanted to ensure that when they finally licked the script for The Great Escape, still three years off as it happened, they would have a grateful director all set.

Especially, they did not want him to fall into the hands of rival producer Hal Wallis who was making a second attempt to set up The Sons of Katie Elder. Sturges had been the original director in 1955 with Alan Ladd in the leading role but a dodgy script. Although the script was in better shape, Wallis couldn’t get Paramount to bite (and wouldn’t until 1965). Another Sturges prospect was a remake of Vivacious Lady (1938) teaming Steve McQueen and Lee Remick in the Ginger Rogers-James Stewart roles, but that also fell through.

“I didn’t want John to go elsewhere and get tied up in another film,” admitted Mirisch. Partly as a means of finding a vehicle for Lana Turner, Mirisch had struck a deal with Seven Arts to make By Love Possessed by James Gould Cozzens, a 1957 bestseller for which producer Ray Stark had forked out $100,000 as a means of finessing his television-dependent company into the movies.

Essentially, Mirisch picked up the picture on the rebound. Seven Arts had fallen out with United Artists which had financed the acquisition of three expensive properties: Broadway hits West Side Story and Two for the Seesaw and the novel By Love Possessed, all of which fell into the Mirisch lap. Mirisch enthused about the two stage productions, interesting Robert Wise in the musical and Billy Wilder, at least initially, in the romantic drama. Prior to The Magnificent Seven, Mirisch had tied Sturges down to a long-term deal and now handed him the script for By Love Possessed. “He read it and said he would like to do it.”

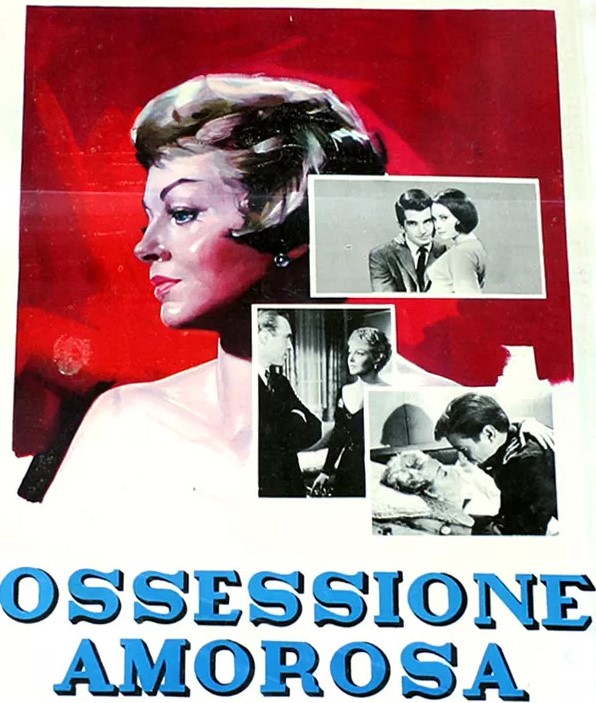

Lana Turner had revived her career with an Oscar-nominated turn in Peyton Place (1957), a huge hit, and had hit gold with remake Imitiation of Life (1959). She seemed the ideal candidate for another adaptation of a seamy besteller. At this point the Mirisch company was still trying to make it way in Hollywood. Its prime method of getting its foot in the door was to pay stars over the odds and allow them greater say in their movies, sometimes backing pet projects. The price of working with big marquee names was often a lot of grief.

Like any other major producer, Walter Mirisch saw himself as a star-maker. Hiring talent on a long-term contract for a low fee was one way of ensuring he could ride on their inexpensive coat-tails in the future. Efrem Zimbalist Jr was the star of hit television series 77 Sunset Strip and the producer “hoped that casting him with Lana in our picture would make him a motion picture star.” He viewed the likes of Jason Robards and George Hamilton as merely supporting actors and not potential stars in their own right, although both would go on to have more stellar careers than Zimbalist.

Ketti Frings, Oscar-nominated for Come Back, Little Sheba (1952), had been paid $100,000 plus a percentage to write the screenplay of what was perceived as a difficult novel to adapt, given it was riddled with flashbacks and introspection. “If we told the book on the screen, we would be making an 18-hour picture,” said Sturges, derisively, as if blockbuster novels (From Here to Eternity etc) were not filetted all the time. Oscar-winner Charles Schnee (Red River, 1948) was drafted in for a rewrite – he had worked on Jeopardy (1953), though uncredited, a Sturges thriller starring Barbara Stanwyck.

Now the screenwriter was dogged with script changes demanded by Lana Turner. According to Mirisch, the actress “never let up” wanting script alterations. But Schnee’s work didn’t meet the director’s expectations and was doctored to such an extent the screenwriter removed his own name from the credits and substituted the pseudonym John Dennis. Mirisch initially brought in Isobel Lennart, who was adapting Two for the Seesaw, for a polish but eventually her version departed significantly from the Schnee original.

Novels could get away with a lot more blatant sexuality than books, though Peyton Place (1957) had made a very good stab at scorching the screen. But the finished script didn’t manage to match the novel’s carnality except in the character of Veronica (Yvonne Craig), the one-night stand who triggers the family downfall. Whatever the problems the script couldn’t nail, Sturges was clearly not the director to get round them with hot onscreen love scenes. Much as he admired strong women, couples getting it on were not his speciality.

The movie was filmed on the Columbia lot with a week on location.

“You get talked into it…or you need the money,” said Sturges. “I knew I had no business making that picture. Sure it was well-acted and staged …but I couldn’t care less about these people. I didn’t like ‘em, didn’t understand ‘em. And if you don’t understand people in a given situation, and you don’t like what’s happening, you shouldn’t try to make a movie out of it.”

Mirisch was as philosophical. “John Sturges was more at home with male-oriented, action pictures than soap opera. I was well aware of that, but I was guilty of ignoring my own misgivings and of wanting to keep him involved in one of our projects while we were doing the script preparation for The Great Escape.” The failure of the movie was, for Mirisch, “a psychological and emotional blow,” one that wasn’t softened by success at the box office.

SOURCES: Glenn Lovell, Escape Artist, The Life and Films of John Sturges (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008) p218-220; Walter Mirisch, I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008) p99, 114-116, 119-120;

So odd to think that Sturges was such an action director, and yet did this to keep the clock running. Didn’t know any of the history behind this, doesn’t normally come up when considering Sturges’ work. I thoght I was thorough by seeing Marooned.

LikeLike

Makes some sense in relation to his ealry career where he was effectively a gun for hire. Despite the pervasiveness of the auteur theory which suggests artists only make the films they want I suspect there’s a rich seam to be explored of them making movies just to stay solvent.

LikeLike