My first cinema all-nighter, back in the early1970s, comprised five Ingmar Bergman films. You try watching back-to-back The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1958), The Virgin Spring (1960), Through a Glass Darkly (1961) and Winter Light (1963) and stumble out into a cold Edinburgh morning without your brain ringing from exposure to one of the greatest filmmakers of all time.

I’m not sure how Bergman would pass muster these days, if he would verge on cancellation, given his predilection, in his private life, for infidelity, often seducing younger actresses – Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullman, Harriet Andersson et al – working on his films for the first time. He had five wives, nine children (not necessarily in wedlock) and countless lovers. He was very much an absentee father, devoting his time to theater and cinema.

Nor was I aware that cinema accounted for barely one-quarter of his creative output. For most of his productive career he spent three-quarters of the year working in the theater, on a huge variety of plays, none of which, that being the essence of that genre, are available to posterity. And he was the first – and possibly the only – famous director to develop television as a serious medium – Scenes from a Marriage (1974) and the Oscar-winning Fanny and Alexander (1982) were truncated versions of much longer mini-series first shown on television. The former was a spectacular success, watched by half of Sweden’s population.

He was also a best-selling author. His autobiography The Magic Lantern attracted an advance of $700,000 (equivalent to $1.8 million now) and sold over 100,000 copies in hardback in Scandinavia alone. His screenplays sold in vast quantities at a time when that area of publishing attracted only minority interest.

With a director as prominent as Bergman there were many interesting what-ifs. Barbra Streisand was slated to star in The Merry Widow, but that came apart after a first meeting, when the director recoiled at her personality. Movies were mooted with Fellini and Kurosawa. Richard Harris was to have starred in The Serpent’s Egg (1977) rather than David Carradine.

At one time he fielded offers from major studios like Paramount and Warner Bros and some of his later movies were funded by mini-majors – The Touch starring Elliott Gould (1971) by ABC and From the Life of the Marionettes (1980) by Sir Lew Grade’s ITC shingle. He was on the shortlist to direct Jesus of Nazareth, eventually made by Franco Zeffirelli.

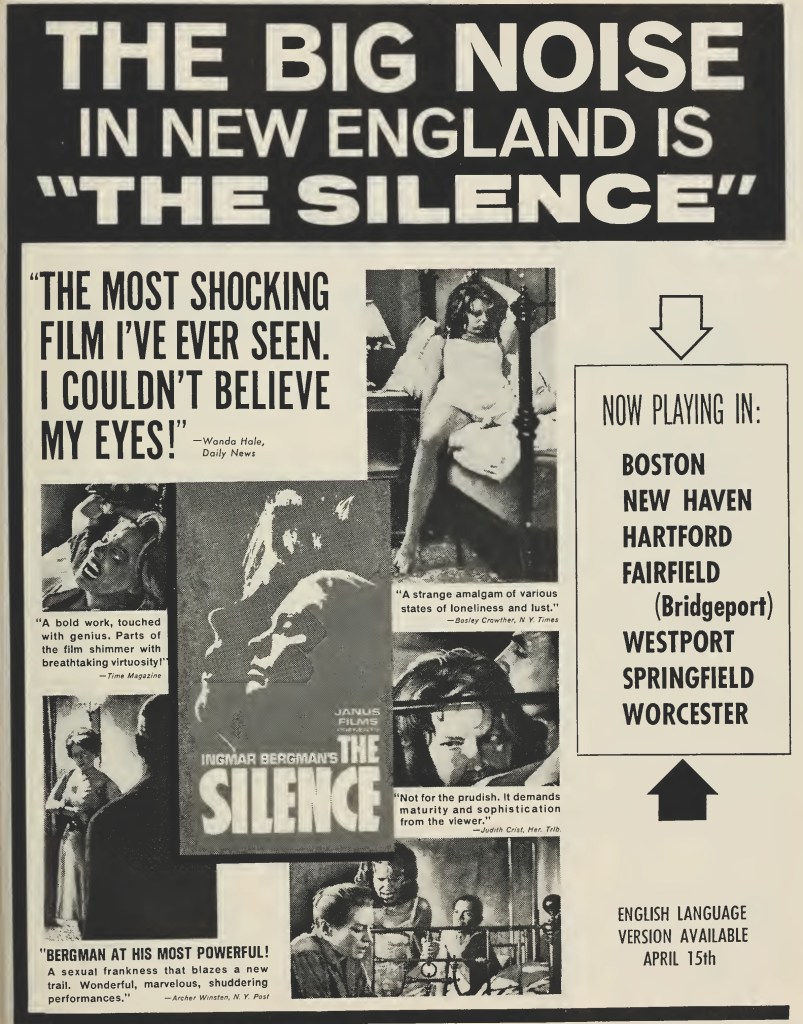

The Seventh Seal, considered his greatest film, despite critical raves, was a flop, The Silence (1963) a whopping success, the biggest box office hit in West Germany for example since the war.

Peter Cowie’s biography, a Xmas gift which I’ve just devoured, has an apt title God and the Devil, for these were the underlying (not to say often obvious) themes of his movies, man giving in to temptation, deity not there to come to the rescue. His films showed the coruscating reality of relationships gone sour, imitating his own experience, even without his constant infidelity (or perhaps because of it) he had a fraught time of it with wives and lovers.

With so many projects – and so many lovers – on the go, his life lurched from professional triumph to personal disaster. Luckily, he could meet child support payments because he was by far the biggest earner in cinema in Sweden, and when wooed by Hollywood, even more able.

Peter Cowie, who founded and edited The International Film Guide for 40 years and ran The Tantivy Press for a quarter of a century, is to film criticism what Bergman is to the movies, someone who moves in the upper pantheon. It was he who interviewed Bergman on stage at the NFT. He claims to come from a generation whose life was changed after seeing The Seventh Seal.

Without being a no-holds-barred work, he does hold Bergman up to scrutiny, the personal life covered in as much depth as the professional. “Bergman’s childhood was clouded by a terrible fear of punishment and humiliation,” writes Cowie, which in essence could have been the template for his movies. He was beaten by his father, a pastor, and bullied by his elder brother. One time, locked in a cupboard, he feared someone was gnawing at is feet.

A cinema buff from an early age, the stage was his first calling and by 1938 had directed his first play. His first movie was Crisis (1946). By Hollywood standards all his movies until quite late in the day would be considered low-budget numbers and it was only when Swedish studios managed to attract international distribution for their films – mostly because of their perceived sexual content – that budgets increased.

While initially The Seventh Seal was considered his greatest cinematic achievement, Wild Strawberries and Persona (1966) have overtaken it in terms of critical approval. In the Sight and Sound Critics Poll of 1972 Persona was fifth and Wild Strawberries tenth. But neither film ever did so well again from the critical perspective though in the Directors Poll of 2022, Persona placed tenth.

A fascinated read and reminder of a director who dominated the cinematic landscape for over two decades.