Setting aside diversity and inclusion issues and the invasion of streamers, the integrity of the Oscars have been under attack for a good few decades. Most observers put this down to the influence of the Weinsteins who began to use the awards as a major plank of their marketing, often spending more on that element of publicity than anything else.

The submission rules are simple: a movie has to play for one week in Los Angeles before the end of the year. That accounts for the rush of prestige-related product in the Xmas period. Occasionally, an entry would be rejected because it was shown outside the strict geographical confines of the city. But mostly movies appeared in this fashion to test the waters.

Even before the nominations were announced, critics and observers would be garlanding various pictures with high praise, anointing them certainties for recognition, which, in the era of social media, was often as good as, if not better than, actually gaining a nomination. And nowadays there’s even mileage if a favorite falls at the last hurdle, endless articles doing the rounds on movies that were “snubbed,” such manufactured outrage bringing extensive media coverage.

In Britain, where I grew up, I distinctly remember a flurry of distinguished movies being released in March/April, capitalizing on nominations and/or wins. In the U.S. the release pattern tended to be more fluid, studios holding back on wide release until nominations were in the bag.

The Weinsteins changed all that by aggressively targeting Oscar voters, helping build the Golden Globes as an indicative precursor to the bigger awards, and creating a marketing tsunami behind any of their movies that got a sniff of a nomination. Eyebrows were certainly raised at these tactics, but, Hollywood turned a blind eye mostly especially in years when box office gross could be achieved by appealing to the lowest common denominator and Oscar bait was viewed as an acceptable route for financially weaker studios or mini-majors.

Although there had always been a few winners that appeared to come out of left field – Marty (1955), the classic example – and the industry displaying a penchant for awarding a best actor/actress award to a neophyte – step forward Yul Brynner (The King and I, 1956) and Julie Andrews (Mary Poppins, 1964) – or to a veteran deemed worthy (John Wayne for True Grit, 1969), it was generally accepted that awards were always genuine and reflected the mood of the time.

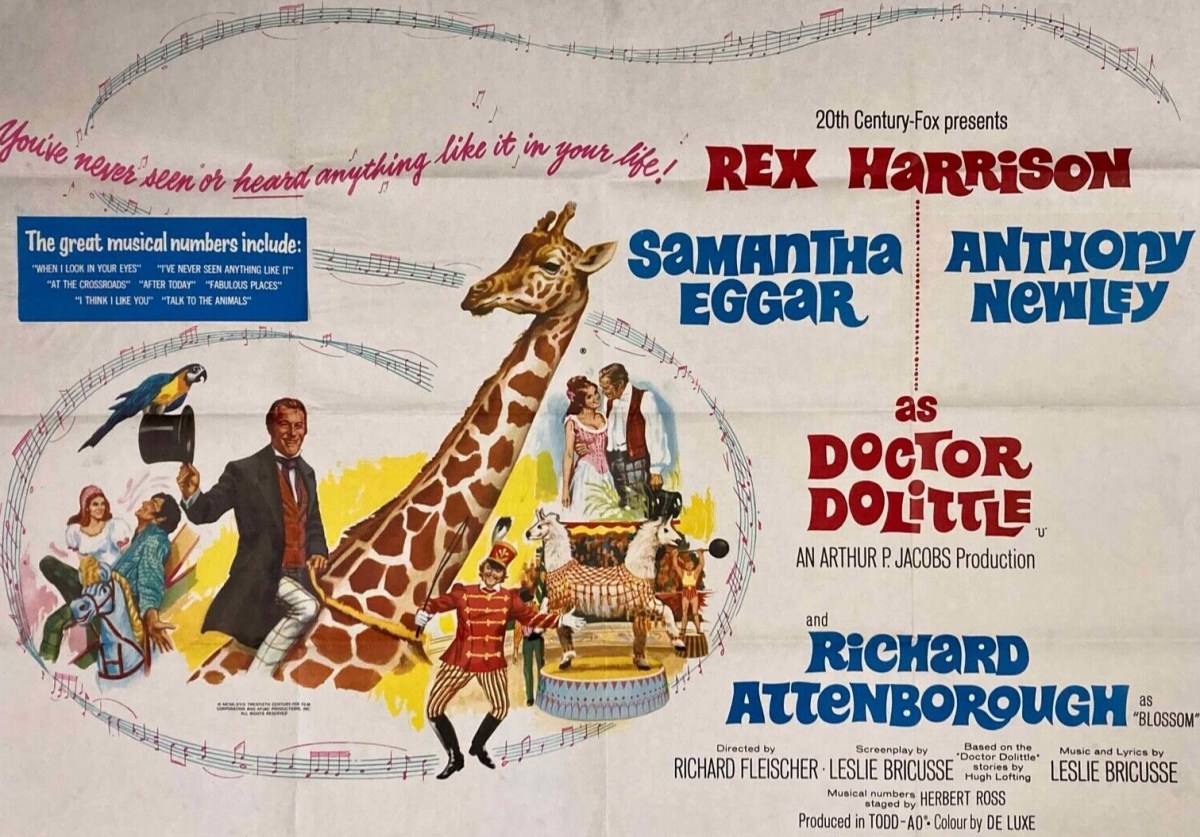

There was no hint of overt machination, of tweaking the system, until observers started questioning just how musical Doctor Dolittle managed to leapfrog into the Best Film category in 1967 ahead of more obvious candidates like Cool Hand Luke and In Cold Blood not to mention Wait until Dark, Point Blank or Accident. Or even better-reviewed and better-performing musicals such as Camelot and Thoroughly Modern Millie.

And it might well have remained just an anomaly until investigative journalist Mark Harris dug out the truth for his book Scenes from a Revolution (2008) which, on focusing in the other, more worthy candidates for Best Picture – Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner – used that to frame his argument that Hollywood had finally come of age in terms of addressing racism, violence and sex and welcoming new talent.

Except that loading Doctor Dolittle into the equation blew a hole in his brilliant thesis, unless he was making a diversity pitch for talking animals. There had to be an explanation. It made no sense that Hollywood denizens who had voted for Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate could be equally enamored of the musical. But, of course, that’s not the way nominations work. At this stage voters aren’t voting for all the pictures, they are voting for an individual favorite.

So, clearly, what had occurred was a major division. It could easily ascribed to a difference in taste. Those who voted for the other quartet clearly shared similar sensibilities. Those who opted for Doctor Dolittle were going against the grain. It was easily explainable as old-timers hitting out as much as older audiences did against a tide of sex and violence, rewarding a return to more innocent times. Or perhaps some kind of recognition that since the musical – The Sound of Music (1965), Mary Poppins – was deemed in some circles to have saved Hollywood then it was only fitting that a new musical should be honored in some fashion.

The truth was darker and left a bitter taste. Twentieth Century Fox, the studio which had put $31 million in production and marketing fees behind Doctor Dolittle and was heading into the same budget stratosphere for Star! (1968), wanted to use Oscar leverage to box office advantage, reviving a picture that was headed for the flop counter and reversing perceived critical disapproval.

In short, it put the screws on any employees who had a vote. There was the usual public campaign that in those days revolved around ads in the trades, but there was also a behind-the-scenes crusade, calling in favors and debts, putting the squeeze on anyone whose career had depended on or might in the near future depend on the studio. Harris argued that Fox had previously adopted this ploy, pointing to nominations for The Longest Day (1962), Cleopatra (1963) and The Sand Pebbles (1966) but, when compared to Doctor Dolittle, these seemed works of cinematic genius.

In the days before VHS, DVD and digital, the only way for voters to get a first or second look at a prospective candidate was for studios to line up showings in private screening rooms or to hire out a cinema for evening, though it would be pretty safe to assume that if your movie was of the blockbuster variety – as in The Longest Day, Cleopatra and The Sand Pebbles – most voters would have already seen it at least once.

To ease access to Doctor Dolittle, Twentieth Century Fox booked out its own theater, plusher than most movie houses, at its studio for 16 consecutive nights. It threw in free dinner and champagne and presumably there was a high-ranking executive, if not the overall boss, to gladhand his way around the post-screening dining tables to ensure the guests knew just how much the studio was counting on them to do the right thing.

While the ploy worked as a method of finding the movie a place at the nominations high table it didn’t appear to sprinkle magic box office dust on the movie. U.S. rentals only came to $3.5 million, less than 15 per cent of its cost. But, probably, in reality it did. Since there was a considerable gap between U.S. and foreign release, it was often foreign distributors who benefitted most from the Oscar aftermath. In this case, Doctor Dolittle’s foreign box office – $12.8 million – far exceeded domestic. It didn’t mean the movie turned a profit, far from it, but it certainly limited the damage.

The damage, in other ways, could not be measured. A studio had interferered with the sacrosanct. Instead of being lambasted, and this being Hollywood, what could you expect except that in future years other studios would take a similar route, resulting in the kind of questionable nomination still going on today, in fact even more pervasively as a result of an upsurge in pressure groups producing often unlikely candidates.

Very interesting! Didn’t realise that the corruption of this institution went so far back…

LikeLiked by 1 person