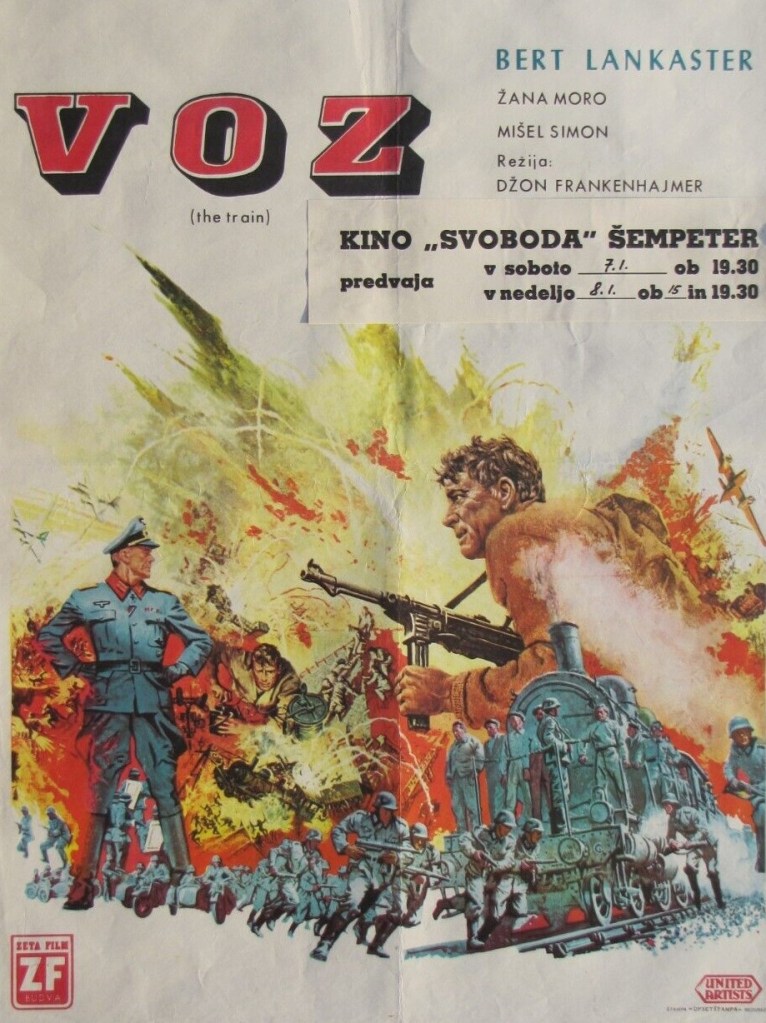

A juggernaut of problems was coming down the track – director sacked, over a year in production, script changing by the minute, way over budget, star Burt Lancaster, his public halo slipping after being caught escorting women who weren’t his wife, earning only 20 per cent of his normal $750,000 fee in order to pay off his massive debt to United Artists. And yet it set the template for “hi-tech shoot-em-ups” such as First Blood (1982) and Die Hard (1988), action pictures where a lone hero saved the day against overwhelming odds.

Lancaster’s hot critical run, Oscar winner for Elmer Gantry (1960), nominated for The Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), had turned sour with Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963). Financially his career had hit an iceberg.

As part of the producing triumvirate of Hecht, Hill and Lancaster, responsible for pictures like Marty (1955), Trapeze (1956) and The Sweet Smell of Success (1957), he found himself in a financial hole, only bailed out when United Artists picked up the tab for the company’s accumulated debt, the actor paying it back with a four-movie deal for which he was remunerated to the measly tune of $150,000 each, a contract he described as “slavery.”

The Train was third on that agenda. It was a risk for United Artists, its first venture into the complex world of the European co-production, this time teaming with French outfit Les Films Ariane. At that point, Lancaster was still considered a creative powerhouse, if not the actual producer, then carrying out a great deal of that function.

Walter Bernstein (Fail Safe, 1964), who had worked with Lancaster on Kiss The Blood off My Hands (1948) and described the actor as “the gorilla on the bus,” was the only one of the original trio of screenwriters – the others being Franklin Coen and Frank Davis – not to receive a screen credit. It was based on a true story, a book Le front de l’art (1961) by Rose Valland. According to that narrative, Germans did try to transport by train a haul of Impressionist paintings. But it was bureaucracy and not the lone hero which prevented it reaching Germany.

But initially, the script had little traction, shelved by the studio until Arthur Penn (Mickey One, 1965) happened upon it. The director’s curiosity was piqued by what he perceived as the peculiar French trait of being willing to risk their lives for art. Penn targeted Lancaster as capable of generating “a certain kind of French sensitivity to the idea of art needing to be protected.” When Lancaster signed on, it was with the proviso Penn direct.

The movie went into production in August 1963, a 15-week schedule, and cooperation from the Louvre, French National Railways, French Army and with a contingent of 40 rail cars. Shots of Nazis in Paris were shot very early in the morning so as not to upset Parisians. The production was based in a small village close to Paris.

Turned out Lancaster and Penn were at odds from day one. Pestered to show “vulnerability” Lancaster decided to show the director “the grin.” Penn only lasted a day, technically two if you include that the following day was a holiday. By 11pm that night Penn was gone. John Frankenheimer who had directed Lancaster in three previous movies, The Young Savages (1961), The Birdman of Alcatraz and Seven Days in May (1964), was his replacement.

Bernstein quit. Lancaster told the writer, “Frankenheimer is a bit of a whore, but he’ll do what I want.”

Why Lancaster didn’t want to make Penn’s version – a quieter film about art (the train didn’t leave the station till about 90 minutes in) – was down to the commercial and critical failure of The Leopard. He needed a hit. And having gone down the arthouse Visconti route, the actor wanted to return to his action roots.

Lancaster showed where the power truly lay. As part of Frankenheimer’s deal, he received a Ferrari; Lancaster told him to keep UA at bay by complaining about the color. Frankenheimer did better than that. He negotiated a credit that read “John Frankenheimer’s The Train.” He evaded French laws that demanded a co-director on set and he received final cut, not to mention a bigger budget.

Production shut down while Lancaster and Frankenheimer hammered out a new script, one that called for, among other things, a 70-ton locomotive, a complete station, more boxcars, signal tower and switch tower as well as a ton of TNT and 2,000 gallons of gas to create the 140 separate explosions for a one-minute sequence that took four months to plan. One of the most striking shots, where the locomotive smashes free and provides a terrific close-up of the upended train wheels spinning, was achieved by accident. Once all the plans were agreed, production was delayed again because winter conditions meant the ground was too hard to safely detonate explosives. The budget doubled to $6.7 million.

Some goodwill was involved. The French welcomed the idea of UA destroying a marshalling yard because it saved them the cost of doing it.

Shooting restarted in Spring 1964. But the schedule was cut to seven weeks, though that include the strafing sequence. You may remember Lancaster had to lug around a wounded leg. That was a clever accommodation. The actor had incurred a knee injury so wouldn’t it be a good idea to find a reason for him to limp such as being wounded. Circumstances – other movies taking precedence after the long lay-off – resulted in the death of Michel Simon’s character.

Injury didn’t tend to hamper Lancaster’s physicality. He runs, jumps, climbs, falls downhill. Said Frankenheimer, “Burt Lancaster (aged 50 mind you) was the strongest man physically I’ve ever seen. He was one of the best stuntmen who ever lived.”

The ending was conceived late in the day. Originally, it was going to be a proper shoot-out. But the idea of Paul Schofield with a gun going up against Lancaster was deemed “ridiculous” so, in effect, the snob German “talked himself to death.”

Reviews were mixed and many found the film too long, one critic complaining, the train “pretends it’s going somewhere and…isn’t.” But somewhere along the way, Lancaster invented the modern action hero.

It didn’t do him much good. The film failed at the U.S. box office but (as Roy Stafford has reminded me) it was in Top 13 in the UK and top 5 in France so there’s a fair chance it at least broke even and may well have gone into profit. Lancaster, forced by UA into making The Hallelujah Trail (1965), another box office calamity, lost out on The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1965) and Khartoum (1967)

SOURCES: Kate Buford, Burt Lancaster, An American Life, (Aurum paperback, 2008) p230, 234-240; John Frankenheimer, A Conversation with Charles Champlin (Riverwood Press, 1995); Charlton Heston, In the Arena (Simon and Schuster, 1995), p315; Tino Balio, United Artists, The Company That Changed the Film Industry, (University of Wisconsin Press, 1979) p279; Arthur Penn Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2008) p15, p45; Matt Zoller Seitz, “Those Hi-Tech Shoot-‘Em-Ups Got the Template from The Train,” New York Times, Apr 30, 1995; Lancaster interview, New York Post, Mar 22, 1965; Jean-Pierre Lenoir, “Stalling a Great Train Robbery,” New York Times, November 3, 1963.

“lost out on The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1965) and Khartoum (1967).” Well, that was a good thing. at least. He was’nt right for those two films. Another top-notch article.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks.

LikeLike

This is certainly a fascinating summary of the background to the production and you list an impressive array of sources. It comes across as a useful account of a Hollywood runaway production but perhaps suggests a missing link. The money I assume came from the US and was channeled through UA’s French subsidiary with Lancaster seemingly having almost complete control. But there were both French and Italian co-producers and the crew and most of the cast were French. How did such a complex action picture get made so efficiently without significant input from French producers? Was Les Productions Artistes Associés set up specifically to make this, UA’s first venture in France?

My other concerns are the box office figures. According to Variety’s rental lists for 1965 The Train returned $3.45 million in North America, making it 19th out of the Top 20 releases. In the UK it was in the Top 13 and in France the Top 5. I can’t find any Italian figures or any other European figures but overall the film doesn’t feel like a financial flop. I looked up the contemporary Sight and Sound and Monthly Film Bulletin reviews in the UK and both were favourable.

The Leopard was perhaps the most notorious case of a Hollywood studio ruining a European film. Having cut 44 minutes from the film, ruining the colour and dubbing it (badly) into English it was not surprisingly a disaster at the North American box office but Visconti’s original Italian film was well received and now viewed as a masterpiece in its restored version (though still missing footage).

LikeLiked by 1 person

As far as I understand Les Artists Associes was simply United Artists translated into French. but you are correct that, with so many crew being French there may well have been a more significant input in that direction than I have suggested. I saw both versions of The Leopard. As I was only too delighted to see a Visconti on initial release I wasn’t too aware of the cuts and it was only when I saw the restored version that I realised how badly it had been mutilated. I’ll be watching it again for this Blog. I’ve amended my Blog to accommodate the box office figures you so kindly supplied. I’m hoping to dig out UA figures for the earlier part of the 1960s to see exactly how it performed worldwide.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m thinking Von Ryan’s Express did better because it was in colour?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never saw the point of the black-and-white idea here. Spend a fortune on explosions in mono? And not because like other films it’s to make use of newsreel footage. Von Ryan had a simpler story as well.

LikeLike