If ever a movie was in sore need of reappraisal it’s Richard Wilson’s western, which encountered both audience and critical indifference on initial release. If you’ve heard of Wilson at all it will, hopefully, either be down to his connection with Orson Welles or from his crime duo Capone (1959) with Rod Steiger and Pay or Die (1960) with Ernest Borgnine. On the other hand, you may be more familiar with the name from the Ma and Pa Kettle series in the 1950s or perhaps raunchy comedy Three in the Attic (1968). Or because he was an unlikely contender for the triple-hyphenate position (writer-producer-director) held on the Hollywood scene by the likes of Billy Wilder and less-heralded figures such as John Lemont on the recently-reviewed The Frightened City (1961).

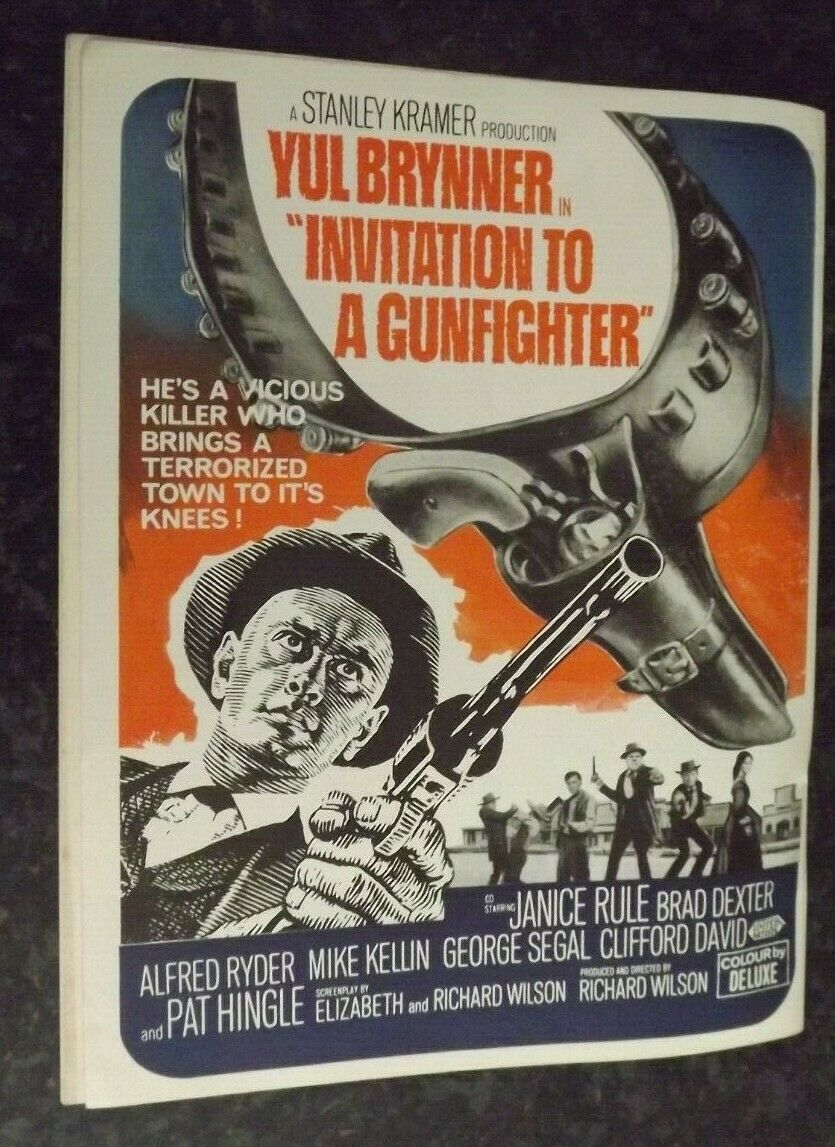

Wilson was not first choice to direct since the western had been on the Stanley Kramer company slate since 1957 when it was planned for Paul Stanley before it moved in 1961 into Hubert Cornfield’s orbit with a script by James Lee Barratt and then repossessed by Kramer when Rod Steiger was briefly attached. The film, backed financially by Kramer, barely rates a paragraph in the director’s autobiography in which he describes the picture as “an adult western with a somewhat complicated plot.” There’s no getting past the fact that the plot is complicated, but it’s not the plot but the characters that held me in thrall. Kramer thought the film contained elements of High Noon (1952). But for me the starting point was surely The Magnificent Seven (1960) and not just because Yul Brynner played a gunfighter complete with black outfit and cigar. It wasn’t Brynner’s look in the previous western that brought me to that conclusion, but the scene where the gunfighters sit around talking about where their career has taken them – to precisely nowhere: no wives, no family, no home.

Invitation to a Gunfighter makes more sense as an adult sequel to The Magnificent Seven than any of that movie’s other retreads. Imagine that Brynner, despite the boost to his esteem from beating the Mexican bandits, had not shaken off what we would most likely classify these days as a malaise or a depression. He is trying to make sense of a life that has proved unfulfilled. His options are salvation or suicide. At some point he will come up against a quicker gun, so it is suicide to continue in this profession.

But this Brynner is also close kin to Clint Eastwood’s man with no name, the mercenary who takes full advantage of his power in lawless towns, and especially to the later embodiment of such a character in High Plains Drifter (1973). (Perhaps Eastwood got the idea of renaming the town ‘Hell’ and painting it red from the scene where Brynner, fed up with the hypocrisy of the righteous townspeople, goes on a drunken wrecking spree.) However, Brynner is far from anonymous. His name is so rich – Jules Gaspard D’Estaing – that the locals curtail it to the more peremptory Jewel. And this Brynner is cultured. He plays the spinet (a kind of harpsichord) and the guitar, sings, quotes poetry and cleans up at poker. He is sweet to old ladies, but that is in the guise of righting wrongs. And he is defender of the under-privileged, in this case downtrodden Mexicans. He was himself the son of a slave. The most compelling aspect of this picture is that despite knowing so much about him he remains mysterious.

Brynner wasn’t the two-fisted kind of action hero, but more the guy who could disarm the opposition with a mean stare, and charm women with his brooding good looks. As mentioned, the plot is complicated so to get the best out of the picture you need to kind of set that to one side. Simply put, Confederate soldier George Segal, returning from the Civil War, finds his farm has been appropriated and his sweetheart Ruth Adams (Janice Rule) has married someone else, the one-armed Crane Adams (Clifford David). Brynner is brought in to get rid of Segal who is causing a nuisance to the town’s immoral hierarchy.

So the story, rather than the plot, is the interaction between these four. Crane Adams clearly wants any opportunity to kill off his rival. Equally, Segal wants to win Rule back. And Brynner finds himself unexpectedly drawn to the sad, pensive Rule, abandoning the Santa Fe stagecoach on catching a glimpse of her, only hired when the townsfolk discover his occupation. Brynner has a fantasy of taking her away from all this, the pair of them riding off together, and there is no doubt Rule is tempted as he implants himself in their household and shows himself to have everything her husband, or Segal for that matter, lacks. Perhaps the best thing about the movie is that nothing is clear cut. Our sympathy shifts from Brynner to Segal to Rule. Even when Brynner brings the town’s hierarchy to heel, there is no guarantee that will be enough to win over Rule. And if he cannot have her, what does he have? The Eastwood loner never seems to care about emotional involvement, he just takes what he wants, but the Brynner character is more sensitive and does not want a one-sided relationship based solely on power.

For the movie to work at all, Rule needs to engage our sympathies. Having clearly been somewhat mercenary herself in discarding Segal in favor of Crane Adams (presumably not originally disabled), she needs to portray a woman who is not just going to jump at the next best thing. Rule is especially good, far better than in more showy roles in Alvarez Kelly (1966) and The Chase (1966). Never given the opportunity to verbalize her emotions, nonetheless in scene after scene her quiet anguish is shown on her face. Magnificent Seven alumni Brad Dexter and John Alonzo (later the famed cinematographer) have small parts.

I certainly saw a different picture to the “offbeat but confusing western” viewed by Variety’s critic and possibly, for once, because the passage of time has allowed this film to be seen in a new light. Rather than a morality play in the vein of High Noon, I saw it as a character study of a gunfighter knocking on heaven’s door.

Many of the films made in the 1960s are now available free-to-view on a variety of television channels and on Youtube but if you’ve got no luck there, then here’s the DVD.